Making modern pipe organs Johann Sebastian Bach would love

While other 8-year-old boys were falling in love with cap guns, flea-bitten mutts or freckle-faced girls with pigtails, John Brombaugh was smitten by the sounds of an old church organ. Sometimes it sounded like thunder, rumbling across the pews. Other times, the music rose like winged angels, singing praise.

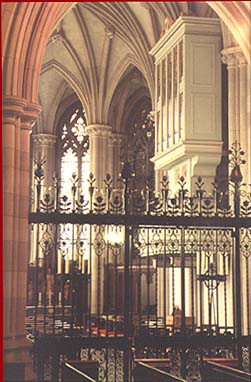

The boy eyed the organ's carved wooden case, multiple keyboards and gleaming pipes, longing to know their secrets. By the time he learned, years later, he would become world-famous for building instruments whose beautiful voices -- like those of Europe's finest historic instruments -- will last for hundreds of years.

Churches, universities and concert halls in 22 U.S. states, Canada, Sweden and Japan proudly display Brombaugh's work today. His organ in Toyota City, Japan, boasts nearly 4,000 pipes and is similar to Cincinnati Music Hall's original 19th century organ, the master builder says.

Because Brombaugh, Eng '60, originally thought his future might be in electrically powered organs, he entered the University of Cincinnati's electrical engineering program. "Coming to the university was definitely one of the most important decisions I ever made," he confirms.

"My education at UC played a very important role in my work as a pipe organ builder, even though one doesn't see much electrical engineering in the type of old fashioned pipe organs I have been making for the past 37 years," he laughs. "But I learned so much common sense from professors Engelmann and Osterbrock and others on the EE staff."

While living on campus in French dorm, Brombaugh listened to recordings of organist E. Power Biggs playing European pipe organs built in the time of Johann Sebastian Bach. The sound seemed somehow familiar.

"The old instruments sounded so wonderful to me," he says, "a lot more musical than organs that are electrically powered. The historic European organs had the same type of internal mechanical action that our old church organ did."

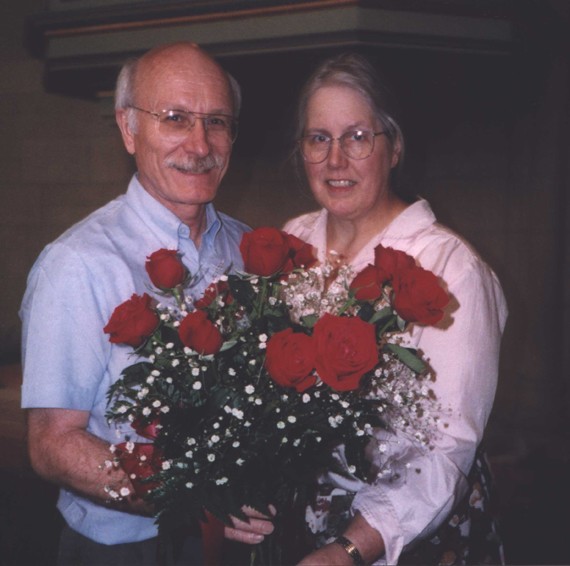

Even though he loved the sound of historic organ music, Brombaugh accepted a job with Cincinnati's Baldwin Piano after graduation. It wasn't his "dream job," but he had an amazing year, directing several research projects and winning seven patents. Then he headed off to graduate school with his bride, Christa Poppe Brombaugh, att. '61. His thesis research? "Organ-pipe sound."

Brombaugh finally decided to go for it: He would build modern pipe organs with traditional inner works. First, he apprenticed himself to master builders Noack and Fisk in Boston for three and a half years. Next, he and his family went to Hamburg, Germany, where he worked as a journeyman with master builder Rudolph von Beckerath.

"This was a wonderful experience," he says. "It forced me to learn German -- the language of most organ-building literature -- and it gave me an opportunity to visit historic organs I had heard years before on the Biggs recordings."

While still an apprentice, Brombaugh built a small pipe organ. It so impressed a professor from Oberlin Conservatory of Music that he asked the young craftsman to build one for his church in Lorain, Ohio. Brombaugh quickly agreed.

The family -- John, Christa and three children -- returned to Ohio where "John Brombaugh & Associates" opened in 1968. It thrived because his instruments were beautiful to hear and see. For example, the metal organ pipes were custom-made, according to Brombaugh's formula: 98 percent lead with 2 percent tin, bismuth, copper and antimony. The metal was cast as sheets, hammered for tone and soldered into cylinders.

"Perhaps the most important thing my work did was to recover a lot of the art of those ancient organs made in the time before Bach," the alumnus says. In late 2006, Brombaugh was honored by the Eastman School of Music, which presented a symposium on his work, as one of two prominent 20th century American organ builders.

Since turning 70, Brombaugh has given up building instruments, but plans to continue his research, writing and consulting about historic organs. Dutch, Italian and Polish restoration teams have already approached him for advice.

"It seems," he muses, "that I will always have something interesting to do."

Updated news

Since the interview for UC Magazine, John Brombaugh was chosen to design a new organ for the renowned German music conservatory, the Hochschule für Musik in Bremen. "It's the equivalent in north Germany to the College-Conservatory of Music, which has made Cincinnati and UC so famous," he writes.

"Beyond that, however, an even more important project was decided. I will be working with two European experts to do a thorough documentation of the organ built in 1551 for the Johanniskirche (St. Johannis Church) in Lüneburg, Germany. It's an organ I would consider the absolutely most significant organ that is still partially extant in northern Europe.

"I have been asked to help document the present condition of the Niehoff organ so it can be restored as much as possible to its premier condition following alterations of 1714. You could put this in a category similar to the recent 'improvements' made to restore the original appearance of Michelangelo's unbelievable frescoes in the Vatican's Sistine Chapel.

"This great organ, I dare say, is not exceeded in magnificence for its time in all of northern Europe, and this project is important to what great organs will be into the future.

"It is also important because Johann Sebastian Bach lived in Lüneburg for three of his teenage years between 1700 and 1703 and studied with the organist, Georg Böhm, who was the organist on the Lüneburg Johanniskirche organ.

"Finally, just this morning I had a phone call from Austria to participate in the restoration of a historic instrument in Linz.

"I am happy that retirement is nothing but a joke and that I still get to work every day on the things my study at UC helped me do so well."

Organ restoration requires documentation

by John Brombaugh, Eng. '60

What I'm doing in the "organ" world is a complicated story, but that is part of the reason I was invited to participate in the work that is planned at the Johanniskirche (St. John's Church) in Lüneburg. In short, it's because I am interested in a type of detail that is hogwash for most people.

The hogwash goes something like this:

Anything historic is eventually likely to undergo some significant alterations -- from great violins by Stradivarius to great paintings by Rembrandt and van Gogh. It's hard for later generations to keep their hands off the wonderful products of previous masters, especially when those works are not yet considered of much significance. This was the case with the Niehoff organ in Lüneburg.

In the mid-1500s, the congregation of St. John's Church, Lüneburg, noted that St. Peter's Church in its sister city of Hamburg had just funded a major alteration of its old organ. Impressed with the improvements in Hamburg, they decided it was a good idea for their church, too. They also chose Niehoff, the most significant organ builder of his time, to do the job, and so the Niehoff organ was built in 1551.

The Lüneburgers were very proud of their improved organ and took good care of it. But in 1580, the church organist realized that this organ, though remarkable in many respects, was not built to certain specifications that were common in Germany at that time, but to old Dutch standards. So they hired a builder from Hamburg to make a minor addition.

In another 50 years, the congregation felt a need to add more notes to the keyboards. Again, the old Dutch standards to which Niehoff had worked did not meet the standards necessary for north Germany. So Kretzmar, a builder of some significance, made more alterations to the Lüneburg Johanniskirche organ.

Adding extra notes to the keyboards, however, meant adding many more pipes to the organ, which caused major alteration to the wind chests in which the pipes fit. That wasn't easy. How do you make such a major change to the fine architectural layout of a magnificent organ case? But all necessary changes were accomplished.

By 1699, Georg Böhm, one of Germany's finest organists prior to J.S. Bach, was chosen to be the new music director at the noted Johanniskirche. Böhm was glad to take such a prestigious job, but noticed pretty quickly that although the organ had a wonderful history, it was not in good condition. Apparently, he put up with the poorly maintained instrument until 1714.

A major rebuild of the Niehoff organ was finished that year by Matthias Dropa, the student of a famed organ-builder in Hamburg. He added a complete new group of stops for the pedal division, which meant he needed to add the towers at the sides to the original Niehoff case that forms the center portion of the present organ.

It's interesting to note that shortly after Böhm took his post in 1699, 15-year-old Johann Sebastian Bach moved to Lüneburg to become a choir member at the nearby St. Michael's Church. Bach was pleased that such a major musician as Böhm was willing to take him on as a student. Whether or not Bach actually ever saw the Johanniskirche organ after the 1714 work was done, we do not know, but the organ was again considered to be a masterpiece.

By the mid-19th century, musical tastes had changed significantly and again the Johanniskirche organ was considered drastically out of sync with the time. In about 1869, a builder named Meyer made a number of major changes to bring the old organ up to the requirements of the Romantic Period. Fortunately, the visual appearance of the case was not altered.

The organ continued into the 20th century without revision until after WW II when the Germans realized that many ideas from the Romantic Period were against the best aspects of the organ in the time of Bach and earlier. There was a strong movement called "neo-Baroque" to return to the old ideas. As a result, Rudolf von Beckerath, who eventually was one of my teachers, was asked to alter the Lüneburg organ.

Beckerath was a master at such things and, within the finances available right after WW II, brought back as much of the greatness of the 1714 Niehoff/Dropa organ as was possible. In the period since 1953, additional knowledge has allowed significant improvements in the appearance of the organ case.

Modern research has continuously studied the ancient arts, and we learn more and more why they are so significant. Since the Johanniskirche organ has resisted the ravages of time better than most organs from the 16th century, the possibility to recover major parts of its original condition is considered very important in our time.

Because I have been so fascinated as to why ancient organs had such great musical thrusts and, therefore, studied them intently, I have been asked to help document the present condition of the Niehoff organ so it can be restored as much as possible to its premier condition following Dropa's alterations of 1714.

I will really enjoy being able to help on something so important in the development of Western history, art and science.

The fact that I know this kind of stuff is exactly why I am so glad to have had the wonderful professors in the UC College of Engineering. They helped me to learn a lot more than "pushing my slide rule."

Issue Archive

Issue Archive