Enduring Nazi captivity from age 9, alumnus Sigmund Rolat honors brother's last request

by Deborah Rieselman

Every job at the Nazi slave-labor camp in Poland was demeaning, demoralizing and draining, yet 13-year-old Sigmund Rolat knew that his was one of the best. While nearly 4,000 Jews toiled endlessly building missile shells on the premises, Sigmund had been chosen to care for a flock of chickens and geese, which kept him outdoors and often on the other side of the barbed wire, where the fowl freely fed next to a brook. Occasionally, he dared to lie down in the grass and dream of a new tomorrow.

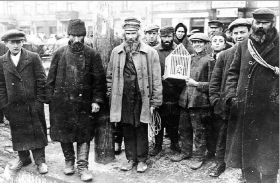

Even better was the fact that his mother, Mariane, worked nearby — inside the Hasag Pelcery munitions factory. Although her job was grueling and her rations miserable, Sigmund realized that 95 percent of the other Jewish women in his hometown of Częstochowa had been transported to the Treblinka extermination camp, where his father had already been taken. Plus, the mother and son’s proximity to each other meant they could usually steal quick hugs each day.

But on July 20, 1943, the boy grew disturbed as he herded the flock along the facility’s main street. Iron hooks supporting naked light bulbs had been installed during the night, creating a scene so bright that it resembled a film studio, says University of Cincinnati alumnus Rolat.

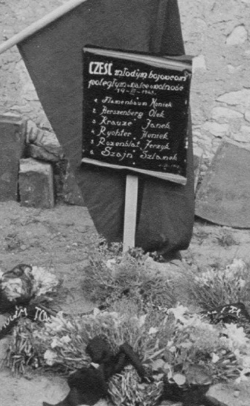

The meaning was obvious. Right there in the middle of the street, the Nazis would conduct a “selection,” where the most able-bodied workers were separated from the rest. The less productive were either transported to gas chambers or mass murdered in the local Jewish cemetery.

“My first impulse was to find my mother,” Rolat says. He ran into the room where she worked and called her name. No answer. He sat down by the machine assigned to her and began crying.

Just then, she dashed into the hall, hugged him and repeated her familiar promise: “Don’t be afraid. Everything is going to be fine.” Believing her was difficult, but the love behind her staunch pledge always made him breathe a little easier.

Outside, they sat together for about an hour on the only grassy spot available until they had to line up in presorted groups to listen to a commanding officer’s speech about how grateful the Jews should be that they were still alive. “There is too much laziness here,” the officer barked over loudspeakers. “The selection is held to take away those who do not measure up.”

Sigmund’s group consisted of 34 young boys, and its existence was a miracle in itself. Nazis did not spare children. Along with women, who could not work as well as men, children were among the first to be killed — a fact he knew all too well.

Past Issues

Past Issues