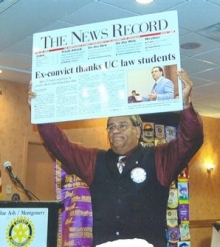

Freeing 17 wrongfully convicted people draws national attention

by Deborah Rieselman

The instant Melinda Elkins caught sight of a SWAT officer sprinting past her picture window with a gun drawn, she stopped breathing. Before she had a second to react, a deputy sheriff showed up at the front door ordering her and her 12-year-old son, Brandon, to move onto the porch where they could not see what was happening on the other side of the house.

Out of sight, her 15-year-old son, Clarence Jr., was handcuffed, lying on the ground, surrounded by officers pointing guns at him. When his father came running from the back door, the officers realized they had cuffed the wrong person and immediately turned on Clarence Sr. Amid the chaos, the younger Clarence heard his mother screaming and dashed for the house with one handcuff still dangling.

In the yard, officers were arresting Elkins Sr. for brutally raping and murdering his 58-year-old blind mother-in-law, Judith Johnson, and raping his 6-year-old niece, Brooke. On the porch, a deputy was explaining to Melinda how she had just lost her mother, had nearly lost her niece and was about to lose her husband.

That was June 1998. For seven and a half years, Clarence Elkins sat behind bars, serving a life sentence for a crime that both he and his wife steadfastly maintained that he had not committed.