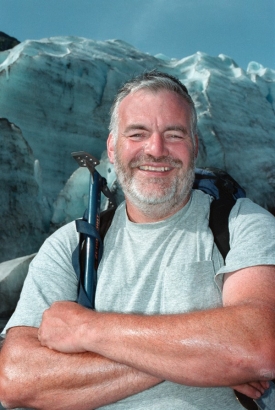

Glacier study keeps professor's passion from melting

by Amanda Hughes

Living in a tent in the cold, barren landscape of Antarctica, Thomas Lowell found his calling. And for 20 years, the UC geology professor has been taking students to remote corners of the globe to study melting glaciers and climate change.

"We've been to places on the planet nobody else has been," he says. "I've seen some pretty dramatic changes. It sinks in a little more concretely when you see it with your own eyes."

To investigate the changing planet, Lowell has literally been to the ends of the earth and back, including Greenland, Bolivia, Chile, Canada, Antarctica and Tierra del Fuego, an island located at the southernmost tip of South America. In New Zealand, a lake now fills a collapsed part of a glacier where Lowell only saw puddles forming in the 1970s. In Alaska, some glaciers have already disappeared.

Glacial behavior is one of the simplest ways to categorize and measure climate change, Lowell says. Glaciers are frozen bodies of water, so if the climate warms, they melt; if it gets colder, they grow.

By looking at glacial patterns over time, Lowell is able to reconstruct climate behavior from 1,000, 5,000 or 20,000 years ago. "Understanding what those patterns looked like in the past can tell us what is happening now and what might happen in the future," he says.

Lowell, who has taught geology at UC since 1986, regularly takes students to Iceland, where retreating (melting) glaciers are easily identified. There, students perform exercises to determine where glaciers were on their birthdates, then measure the distance they have retreated. Older students find a greater distance than younger students.

Although such patterns tell us what we might expect in the future, Lowell says one key variable is altering the climate for the first time in earth's history. "There's increasing evidence that Homo sapiens' agriculture and construction are changing the chemistry of the atmosphere with the introduction of CO2.

Issue Archive

Issue Archive