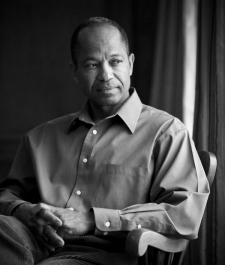

From enslavement to enlightenment

University of Cincinnati alumnus loses childhood to slavery, then dedicates his life to saving other Haitian children through education

by Joe Rudemiller

At 4 years of age, Jean-Robert Cadet was "given" to another family shortly after his mother died. Most Americans likely assume that means he joined a new family, perhaps as a foster child. But in Haiti, where alumnus Cadet spent the first 15 years of his life, a child who is given to another family generally becomes an unpaid domestic worker -- often treated as a slave -- known as a restavek.

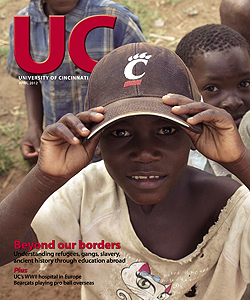

Originating from the French expression reste-avec, which means "to stay with," the term restavek is used in Haitian culture to describe children who live with families without being considered members of those families. In most cases, restavek children are responsible for performing lengthy daily chores like scrubbing floors, carrying buckets of water long distances and cleaning chamber pots, instead of going to school.

They are often abused -- physically, mentally, emotionally and sometimes sexually.

A restavek from age 5 to 15

Cadet understands what it is like to never have a childhood due to all of those abuses. He served his "family" as a restavek from age 5 to 15, suffering unimaginable abuse the entire time and even being lent to neighbors and friends to work for them, too.

"We were -- these kids are -- the lowest of the low, just treated like dogs," Cadet says.

"You don't eat at the table with the family. After everybody has eaten, if there are some scraps left, you get that -- just like a dog. And a lot of situations are still the same today."

But Cadet, M (A&S) '94, is desperately trying to change that. He has made opening doors for other restavek children in Haiti his life's mission, using knowledge as the key. Not only have his efforts gained international attention, but one of his recent partnerships also involves the University of Cincinnati.

Cadet came to the United States in 1969 when he was about 15. (He does not know his exact age, as his birth was never formally documented.) The family with whom he lived immigrated first, abandoning him in Haiti. Within a few months, Cadet proved himself resourceful enough to find a way to show up at their New York doorstep, where he continued in his role of servitude.

Required to attend school in U.S.

Shortly after his arrival, the family learned that children in the United States were legally required to attend school, so they enrolled him for classes. Suddenly, Cadet was given an opportunity to learn, something he had always desired. Just like that, a door was opened that he would never allow to close.

Soon, however, another door closed; the family kicked him out. Homeless, he slept in a nearby laundromat and wherever he could until he graduated from high school. Afterward, he enlisted in the Army, graduated from the University of South Florida and later began teaching in Tampa, where he met his future wife, Cindy, originally from Northern Kentucky.

The couple moved to Cincinnati, where Cadet continued teaching, first at the Academy of World Languages, then at the School for Creative and Performing Arts. In 1990, he enrolled in the master's degree program in French literature at UC in order to improve his teaching skills.

During his time at UC, Cadet began writing his first book, "Restavec: From Haitian Slave Child to Middle-Class American," which gained international attention following its 1998 release. The book started as a letter to his son, Adam, as a way to explain the atrocities he faced growing up. But as the length of the letter continually grew, it took the shape of a memoir. "My letter to Adam would become a letter to the world," Cadet says.

"It grew into something much more than I had anticipated. It propelled me to the United Nations, and I found myself speaking at the International Labor Organization. Then the word restavek became known, and my name became associated with it because I'm the only one who has written a book about that experience."

Mountain of despair, stone of hope

Last year, he published his second book, "My Stone of Hope." The basis for the title -- and the epigraph -- is a quote from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech: "… we will be able to hew, out of a mountain of despair, a stone of hope." Cadet's modest nature may keep him from putting it so bluntly, but the reality is that his life embodies that quote. His goal -- a lofty endeavor, to be sure -- is to eradicate child slavery in Haiti.

Since his first book was published, Cadet has become one of the foremost advocates in the fight to end child slavery in Haiti. He has testified before the United Nations and U.S. Congress, and appeared on "The Oprah Winfrey Show," CNN and "60 Minutes" to make the plight of Haiti's children known throughout the world.

In 2007, he permanently quit teaching to dedicate full-time efforts to a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization he founded to end Haitian child slavery, then left that organization in 2010 to found the Jean R. Cadet Restavek Organization. Every six weeks, he travels to Haiti to continue work on his project.

Due to the nature of the restavek culture, no one can accurately determine the number of such children currently living in Haiti. Estimates vary from 173,000 to 300,000. But Cadet believes the number might even be higher as a result of the massive earthquake that hit Haiti in January 2010. Regardless, Cadet is convinced that even one child living in domestic servitude is too many.

"The plight of those kids has become my passion. I'm driven to do something about it," he says. "I have to do something. I have to end it."

Changing the hearts of a generation

Although it goes much deeper, Cadet's plan for achieving his goal can be summed up in one word: education. So in March 2010, he approached the director general of the Haitian Ministry of Education about implementing a national curriculum for elementary school students that focused on respect for the environment and for other people.

After learning the director was open to the idea, Cadet enlisted the help of Cady Short-Thompson, dean of UC Blue Ash College. She put together a team of professors from UC and Northern Kentucky University, who began creating the new curriculum. The finished project has since been translated into Haitian Creole.

Because 90 percent of Haiti is deforested, the curriculum first teaches children to respect the environment. After all, without an environment, there will be no future for Haiti, restaveks or not. Then it transitions to respect for equality, liberty and brotherhood -- the principles upon which Haiti was founded, but which children of Haiti do not understand.

With a pilot program scheduled to be implemented at a test school in 2012, Cadet hopes that the curriculum will be ready for national use in 2013.

"To end child slavery, you have to influence a new generation," he explains. "The adults are set in their ways. I really think education is the only way, because you have to change the mentality of the new generation, so the next generation will have a different way of looking at each other, looking at children."

Cadet realizes that changing the hearts and minds of an entire generation is no small task, and that it will likely be decades before any progress comes to fruition. But if, and when, his new curriculum takes hold, perhaps the education that hewed a pebble of hope from every restavek child's mountain of despair will become the chisels used to carve a boulder of hope for the entire nation.

Joe Rudemiller is a freelancer for UC Magazine.

Links:

Cadet's restavek organization

Cadet's first book: "Restavec: From Haitian Child to Middle-Class American"

Cadet's latest book: "My Stone of Hope"

Past Issues

Past Issues