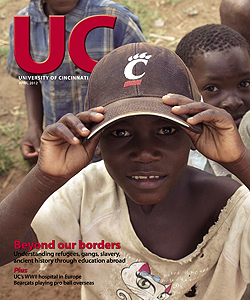

CCM students and African refugees bond through theater

by John Bach

Balancing 8 feet above a field in Africa, Will Kiley found his "why."

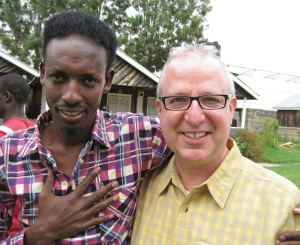

In Kenya's Great Rift Valley 8,000 miles away from UC, the 20-year-old UC drama student's once-comfortable world began to come unglued. It was there over that field -- his 6-foot-4 frame perched on 14 sturdy arms -- that he locked fists and eyes with an Ethiopian refugee named Ojullu, who was also lifted high and horizontal above the lush grass.

"Come on, Kiley, take my hand," Ojullu Opiew Ochan called out with his thick accent. "Don't let me fall."

The line on which the performers' hands connected was from a poem the fast friends had co-authored at daybreak while sitting at the edge of a hippo-filled Lake Naivasha. Ojullu's plea was particularly poignant given that the 22-year-old had seemingly been in a free fall since age 14 when he witnessed a massacre in his village that claimed his parents. His cry was further hardened by eight years as an orphan in Dadaab, the world's largest refugee camp and the place he would return to after the performance.

"We cannot fall," the men recited as they closed the piece together. "It is not within us."

Past Issues

Past Issues