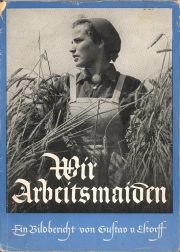

Life in a Hitler labor camp

UC student and young alumna had a summer vacation worth writing about

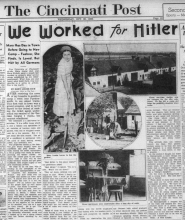

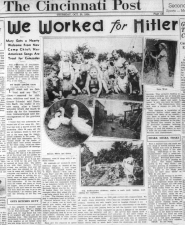

"We Worked for Hitler." So shouted the banner headline on the Cincinnati Post’s front page. It was fall of 1936, and for 16 days, those four words appeared over the paper’s first-person series.

For local news, this was pretty surprising, but the facts were even more astonishing:

- The primary author was a UC student, and the other writer a new UC graduate.

- They traveled alone for two and a half months.

- Both courageously volunteered for a month-long camp commitment in the Reich Labor Service for Female Youth so they could write about it.

- One of them knew no German.

- The other one refused to give the obligatory Nazi salute each day.

To put it in context, it was true that World War II had not yet broken out and Americans weren’t entirely sure what this German madman was all about. But Hitler had scared enough people to ignite a giant debate the year before regarding U.S. participation in the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Although the American Olympic Committee, with the blessing of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, decided to send competitors to the games, two U.S. athletes simply sat out, not wanting to set foot into Nazi territory.

At the same time those two athletes were making their stand, two youthful UC writers were packing their bags — Mary Louise Eich, A&S ’37, and Mary Nichols, Ed ’36. Unfortunately, we have no record as to what triggered their decision to dance with danger. Eich died at the early age of 39 due to tuberculosis, and Nichols had no records in the alumni database.

We do know that Eich was a 22-year-old student studying journalism, who wanted to share the inside story of living with the Nazis when she arrived back home. Their series of newspaper articles, from Oct. 24 to Nov. 12, 1936, revealed that everywhere the women went, people were shocked to see young Americans in Germany. Apparently, few other Americans volunteered for such an adventure.

Eich dreamed up the plucky plan and wrote 11 of the 16 articles. Germany was encouraging youthful international travelers to help spread its socialistic ideals. She wrote to the Institute of International Education for permission to join a camp. Her Roman Catholic upbringing and two German-immigrant grandparents helped her obtain approval. Next, she asked her Delta Zeta sorority sister Nichols to accompany her.

Neither of them had a solid idea of what they were getting into.

Facing the unexpected

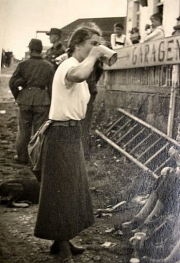

Eich spoke German well enough to be confident, but poor Nichols knew none of the language. As a pair, they functioned fine, but when they reached Germany and received their assignments, their camps were unexpectedly 80 miles apart.

In one of the columns, Nichols wrote, “My German, or lack of it, shrouded me in an enforced silence, which soon became almost too much for me. And so I began to grow toward a hybrid of the speechless and the actress. What would I do without my hands?”

Eich ended up at two different camps because she had gotten kicked out of the first one for failure to salute. Somehow she survived the second one, though her stories never revealed how.

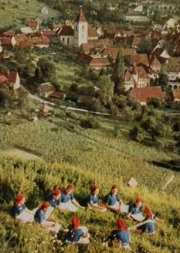

According to their accounts, as many as 48 women — at an average age of 20 — lived at each camp for six months. Germany had hundreds of camps, where young women were expected to live by two Nazi truths: “Bread comes hard.” “Work ennobles.”

Eich explained that camp service was mandatory for any German girl wanting post-secondary education, even at a secretarial school. The government also recruited additional young women from among those unable to gain satisfactory employment following high school, those who were engaged and needed to keep busy until their weddings and those whose parents disapproved of their boyfriends.

To avoid the camps, some high school graduates simply passed up the chance to study at a university, which is the reaction the government had wanted from the girls all along. In 1941, a yearlong obligation to the program would become compulsory for girls.

Eich tells us that the Nazis called for women’s lives to center on husbands, children and homes. At her first camp, the leader told her, “Our Führer wishes every woman to marry and have children.”

Consequently, the government discouraged women from holding jobs or enrolling in anything beyond primary education. Physically, they were expected to be sturdy, strong and healthy. The camps promoted those goals.

Schedules not like home

Half of the girls enrolled in the Hitler program worked all day at camps, Eich wrote. The others worked for local peasants, usually walking an hour each way to reach their posts. Assignments rotated, giving each girl a taste of various responsibilities.

Based upon this pair’s experiences, women slept on straw mattresses, arose around 4:30 a.m. and immediately pulled on gym suits to exercise in the cold air. Afterward they bathed with icy water in a basin, donned uniforms of smocks and bandanas, readied their rooms for inspection and attended a flag-raising ceremony where saluting was required. Next they had a breakfast typically of barley coffee, pumpernickel and jelly.

From there, each girl in the camp went to her appointed destination, either walking there or starting her camp job immediately. Sample tasks included tending crops, harvesting grain, washing clothes over a cauldron on a brick stove, ironing and kitchen duty.

Heavy labor lasted until 9 a.m. or so, when a “second breakfast” was served, perhaps two hunks of tough, coarse bread held together with a chunk of fat. Chores stopped again for a nourishing dinner near 1:30 p.m., after which work continued until 4 p.m. — or 3 for those who had an hour hike back to camp. Mandatory naps took place at 4, school began around 5, supper at 7 and “singing practice” of patriotic songs at the end of the day.

School lessons focused on history, politics, hygiene, anatomy, agriculture and “housewifely” duties, Eich called it, such as sewing, washing, cooking and decorating the house. The latter, she explained, featured making “lovely things,” such as clay vases, latticework lampshades carved from wood, embroidered wall coverings and even bookcases.

On Saturday nights, they learned folk dancing to preserve old traditions. In the fall and winter, camp participants would teach the dances to peasants who had forgotten them.

A real ‘labor’ camp

There was a reason these camps were called “labor” camps. No matter where a woman toiled, each day was indeed laborious. At the end of Eich’s first day, she reported, “It took three pairs of helping hands to boost me into my top bunk, for I had completely lost the use of my leg muscles from seven hours of bending in the garden.”

She also had a stint of binding and stacking rye in the field. The work slashed tender skin on the inside of her arms, scratched her feet and legs, created “stinging welts” and tore back her fingernails, she wrote. “The muscles of your back, the ones you never knew you had, become fiery pains burning and stabbing into the chest.”

Operating threshing machines was another trying time. The machines threw chaff in her face, coating her with fine black dust “inside and out,” she recorded. “My lungs and eyes hurt the most, and it was a couple of days before my eyesight ceased to be fuzzy.”

Even chores as mundane as peeling potatoes were difficult, due to sheer volume. “My night task was peeling potatoes for the next day,” she told readers. “Between that and peeling potatoes for the peasants, I developed such unmistakable finger calluses that, in Berlin after camp was over, young people familiar with the labor service had only to glance at my hands to tell me what I had been doing.

“The work camps are supposed to be health builders,” Eich added. “My observation led me to doubt this. There were always four or five girls, sometimes more, in bed from exhaustion.”

Free time also made her weary — weary of listening to politics. “The songs we sang, books we read, everything was political. In the little free time we had, the girls talked seriously with me of politics.

“Hitler wishes these young women to become good wives, but it seemed to me that he was setting about this in a funny way. When an 18-year-old girl finds her greatest pleasure in political discussion, there is something wrong somewhere.”

One thing Hitler had certainly accomplished was cultivating devotion. “The leader is beloved,” Eich acknowledged, “not universally, to be sure, but the mass of the people, even those who do not approve of all his policies, love him as a man and their friend. He is not ‘the’ leader, but ‘our’ leader.’”

Life outside of camps

One weekend, Eich obtained permission to “take up the German sport of wandering,” which means just what it says. She donned old clothes and slung a camera, map case, canteen and knapsack over her shoulders, then simply wandered through fields, forests and hills — all alone. In particular, she headed for Germany’s eastern border to meet some Polish people — no one in particular.

The move was bolder for a young American woman than she suspected. About 10 kilometers from the border, a bicycling “gendarme” (police officer) “streaked up” behind her demanding to know who she was and where she was going.

Her answers annoyed him, and her passport even more. After an hour of her pleading and looking tearful, he let her go with a command to look up the police in the next town.

The next town was actually her destination. Although it sat on the German side of the border, she knew its population was Polish. She entered town excitedly, but quickly ran into an officer who ruined everything by refusing to let her stay in the local inn.

“No, you can’t do that,” he told her. “These are Polish people and not like Germans. You might not be safe.” He insisted that she sit on his handlebars so he could deliver her to the nearest German inn, instead.

Never willing to settle for boredom, Eich found guests at the inn discussing Germany’s “military secret,” which would make them invincible. “Just what the nature of this military secret is,” she noted, “no German with whom I spoke knew, but most of them firmly believed in it.”

In the morning, she again drew police attention as she walked to the border. With law-enforcement officers running at her, she had no recourse but to fall back on a technique she had recently cultivated.

“I had learned that an expression of eagerness to please, mixed in the proper proportion of innocent helplessness and a suspicion of tears, will melt the toughest German policeman. So we were soon very good friends.”

Getting a real dose of politics

When their 30-day labor-camp commitment ended, Eich and Nichols reconnected and traveled to Berlin for four more weeks. They ended the expedition attending the eighth annual Nazi Party Congress in Nuremberg for a week.

“The greatest show on earth,” Eich called it due to its size and splendor. Simply put, it was an enormous propaganda event with 120,000 people packed onto Zeppelin Field, many of them youth.

Afterward, she confessed, “It takes a strong fight to keep your reason and judgment clear. Everyone wants to talk politics, and that means fencing and guarding every word that leaves your lips.” She summed up her views in the Post’s final story:

“People seem to think that you can go to Europe and come back with your mind made up about international politics,” she wrote. “You can’t. A lot of people love Hitler for good reason, and a lot hate him for equally good reason.

“Two things you can’t do: judge the ethics of dictatorship by American standards and believe everything you hear. Everyone has an idea to sell.

“You make friends, and half of them are trying to worm out of you the secrets the other half have begged you never to betray. You become distrusting, suspicious, and the back of your mind is always questioning motives. Silence becomes the most important rule of life.

“There are few things you can be certain of, but war is one of them. There will be war between Germany and Russia in the near future. The real war, though, is between Fascism and Communism.

“Even if the Germans were alone, they wouldn’t be afraid of death or the devil. Their military strength is unbelievable.”

Of course, her prophetic words were true, even though she did not go as far as to suggest that the U.S. would eventually join the war.

She did, however, quote one of her like-minded acquaintances who expressed grave concern over the Nazis. “If I ever have to fight another war,” he noted, “I hope these babies aren’t on the other side.”

All we know about Nichols after the trip ended is that she remained unmarried and died in Cincinnati in 2001.

As for Eich, we know that she joined student relief efforts during the historic January 1937 flood. Among the volunteers was medical student William Neal, who caught her eye, and they started dating.

After graduating from medical school in ’38, Neal took an internship in San Diego. In September 1938, the couple married in Tucson. A son, William, was born in West Virginia in January 1940. Six more children would follow. She died in 1954.

During the years after their trip, both women would discover what a horrible era followed Hitler’s youth camps. Construction of major concentration camps and aggression against the Jews grew yearly: Buchenwald camp in ’37, Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass) in ’38, the notorious women’s concentration camp Ravensbrueck in ’39, Auschwitz camp in ’40 and Hitler’s decision to begin mass extermination of the Jews in ’41.

* Much of this article’s content came from the book “An Odyssey in the Life of Mary Louise Eich,” written by her son William Neal and published in 2011. The book contains all 16 articles in the newspaper series.

Click on any photo to enlarge it and enter into a slidshow photo gallery. These photos were initally published as propaganda.

Click on any photo to enlarge it and enter into the photo gallery.

All photos below were German publicity shots to aid in recruitment. Courtesy of the Federal German Archives.

.

Past Issues

Past Issues