by Chris Curran

THERE'S NO SUCH THING AS AN UGLY GLACIER. They do get a bit dirty in the summer when the winter snow melts off, but there really is no such thing as an ugly one.

I learned that lesson the hard way, trekking across 14 glaciers in south central Alaska for three weeks last August with UC geology professor Thomas Lowell and a group of students less than half my age. Lowell has studied glaciers as far away as Antarctica and New Zealand, and taught his Glacial Field Methods course in Iceland, Canada and the U.S. So he's seen a few glaciers over the years.

Yet no matter how hard I pressed, he would not name a favorite, simply saying with a smile, "There's no such thing as an ugly glacier." He treasures them all, and so do his students.

My adventures with the geological explorers, along with UC photographer Colleen Kelley, began with a hike up some snowy slopes to see Byron Glacier about an hour outside of Anchorage. Billed as the "easy, warmup hike," it seemed exhausting to me.

In the morning, as we approached Exit Glacier, I better understood the "easy" label. In less than an hour, I had reached the conclusion I was doomed.

"How high are we?" I wailed plaintively. "Not high enough," barked Dr. Lowell. He did try to encourage us, promising, "We'll climb just a little bit farther, and then we'll get some spectacular views."

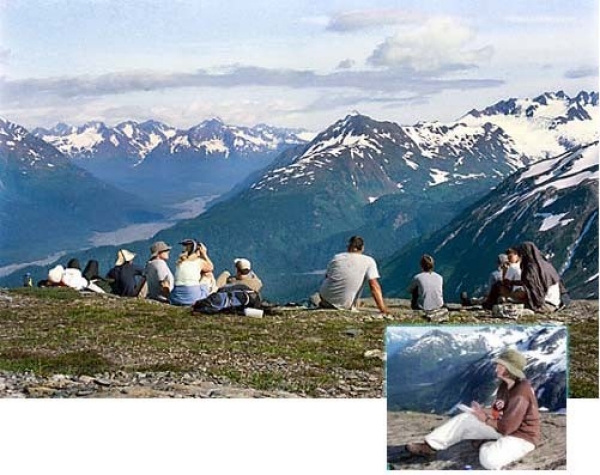

Professor Lowell told us the climb would be on a relatively gentle slope covering a mere 3,000 feet in elevation. So why did this "simple hike up a hillside" take us six hours? Why did Colleen and I need to be "rescued" by Lowell who played pack mule and carried our gear the final 300 feet? And how did the students have the energy left to run from our spectacularly scenic plateau to the snowfields marking the beginning of the Harding Ice Field?

I asked a lot of questions during the trip. I got very few direct answers.

"I could tell you what to do, and you'd be done this afternoon, but if you discover it on your own, it's a far more valuable lesson," Lowell explained more than once to students frustrated at understanding how glaciers have changed since the Little Ice Age. Short answer: They're melting away at an increasingly rapid rate. The glaciers we enjoyed on this trip won't be the same next year, or even next month.

After the two-hour climb down Alaska's Exit Glacier, UC students discovered they were returning the next day. Thankfully, it turned out that the best way to study a glacier was not to climb 3,000 feet to a plateau, but to "bury your nose in them."

Past Issues

Past Issues