Betrayal for justice

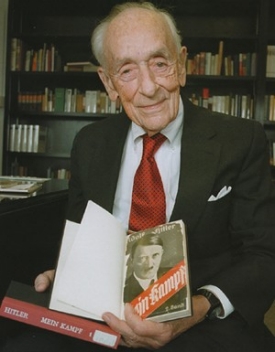

Werner Von Rosenstiel, a German exchange student in 1935, returned to UC in 2001 to donate his collection of German books, now housed on the third floor of McMicken Hall in a reading room named in his honor.

"Heil Hitler!"

These sinister words punctuated Werner Von Rosenstiel's 1939 letter graciously accepting a lifetime position with the German Ministry of Justice. The message, and particularly his hollow salute to the Fuehrer, was a lie, a bold attempt to deceive the Nazis, a conspiracy to escape his own country.

Though the war machine had grand plans for the 28-year-old Aryan attorney who had just recorded the top score on the German bar exam, Von Rosenstiel had no intention of joining Hitler's cause. Disgusted by Germany's interpretation of justice, particularly its treatment of Jews, the young lawyer and Wehrmacht draftee hatched a scheme to abandon his homeland and return to the United States to wed the woman with whom he had fallen in love years earlier as an exchange student at the University of Cincinnati.

Von Rosenstiel requested in the letter that his commencement of service be postponed by 30 days so he could revisit the states to shore up his English. Agreeing the language skill might certainly prove valuable in the war effort, likely needed to interrogate prisoners of war, his superiors granted permission. The lanky German returned not 30 days, but almost six years later during the Battle of the Bulge, as an American soldier.

He indeed faced his Nazi bosses again and even put his highbrow German legal education to use, but certainly not as they had envisioned. Ironically, he helped determine their fate during the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials. Long before Nuremberg, however, Werner arrived overseas in America ― for the second time. It was Aug. 17, 1939, two weeks before the outbreak of World War II.

Though he was a gifted German lawyer, his foreign legal skills were nearly useless in the states, and his fragmented English forced him to take a job unloading boxes in New Jersey. His new wife and one-time Cincinnati sweetheart, Marion Ahrens, insisted that he continue his education in the United States, which eventually led to a law degree from Fordham University and equipped him with the appropriate parchment to practice law on both sides of the Atlantic.

Today, 90-year-old Von Rosenstiel, who retired from firms in Philadelphia and Germany, credits his American education, and particularly the year he spent at UC in 1935-36, for his blessed life. For he not only found his wife here, he discovered a nation, a society, for which he would later risk his neck.

"Cincinnati, without my knowing it, was the turning point in my life," the statesman-like speaker told members of UC's history department during an oral history interview last year. "It was here in a political science class that I heard for the first time a peculiar statement that every American knows: 'We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal.' This was something that was very much in variance to what I was used to in Germany."

The skilled orator is proud of his "perfect German," but his tongue still labors to pronounce the English "th" and "w." He uses a cane, wears a matching set of hearing aids and needs a magnifying glass to view photographs and small print.

Traveling to Cincinnati with two other German students was a memorable trip for Von Rosenstiel (center). He made the journey with Dietrich Zwicker (left) and Herbert Beyer (right), who dropped him off on their way to college.

Time has not, however, overrun Von Rosenstiel's crisp memory. He effortlessly recalls a second epiphanic moment that occurred 66 years earlier during a "bull session" in the UC dorms. The subject was Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal.

"Suddenly one of the students said, 'You know that Roosevelt, that son of a bitch.' As he said that, I jumped up and said, 'Just a minute, you can not say your president is a son of a bitch.' The guys laughed at me and said, 'Werner, you are in America now.'

"There was a sudden realization that, 'My God, you can say that, and you don't go to jail. And you don't go into a concentration camp.'"

Those pillar democratic ideals, from his crash course on the Declaration of Independence to his first taste of free speech, sunk deep into Werner's psyche and never left, not even when the same government he championed accused him of being a spy.

The Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor instantly turned many Japanese and Germans living in America into enemy aliens. In the eyes of the Department of Justice, Werner's past was suspicious if not incriminating. After all, he was once a soldier in Hitler's regime. He still has the enemy alien card he was issued limiting his travels to Manhattan, where he lived, and New Jersey, where he worked.

Interrogated by the FBI and eventually tried on Dec. 7, 1942 ― a year to the day after Pearl Harbor ― by an Enemy Alien Hearing Board, Von Rosenstiel had his life sniffed and picked over by hostile agents and prosecutors who were convinced he had come only to spread propaganda for Hitler. The copy of "Mein Kampf" the FBI took from his apartment didn't help matters. Though Werner managed to convince them that he possessed the book only to study Hitler's writings to prepare for the German bar exam, it was the testimony of his witnesses at the hearing, particularly, his wife, Marion, now deceased, that saved him from internment or deportation.

She stood before the judges with a postmarked envelope in her trembling hands and read from a letter her beau had penned from Berlin following Kristallnacht, "Night of Broken Glass," the 1938 organized anti-Jewish riots in which dozens were killed, thousands were forced into concentration camps, and synagogues, shops and homes were ransacked. "It was so very, very disgusting to see all these riots, the smashed windows and the cruelty," he had written. "My feeling of humanity and my belief in the human race is almost gone, at least gone as far as the people in this country are concerned. Please tell Sigmund that I am ashamed and that no matter what this country does to his people, I want him to know I am his friend."

Among the many items Von Rosenstiel left in UC's care are documents and photos he collected from Germany during World War II.

The enemy alien board believed Marion and paroled her husband. Within three months, he was drafted into the U.S. Army.

It was not the last time his devotion to the United States was scrutinized. After basic training, Von Rosenstiel was assigned to a military camp for undesirables in Pennsylvania, the Foreign Legion.

Still considered an enemy alien, and particularly dangerous given his formal German education and his skills with a rifle, the U.S. Army lumped him together with conscientious objectors and other soldiers from "questionable" ancestry. Instead of the traditional olive drab or camouflage fatigues, the Foreign Legion wore blue denim. Instead of readying him for the war, the Army assigned Werner to wash dishes (kitchen police, KP) and build sidewalks.

"Nothing that I experienced, before or after, challenged my faith in America more than those three months," he wrote in his memoirs. "They wanted to explore what we believed, whether we could be trusted or whether we should be assigned permanently to KP."

Luckily for Werner, his U.S. citizenship came through, and soon he was shipped out of the foreign legion to a laundry battalion, then to an IBM computer outfit. Before long, the Army recognized his legal education and assigned him to assist a military judge writing briefs and court martial opinions. When it was determined he was not a spy, he was shipped to Europe with an airborne unit during the Battle of the Bulge, months before the war's end.

The Army soon realized the value of Von Rosenstiel's background, promoted him to second lieutenant and sent him to the War Crimes Unit in Germany to read secret files. Upon reentry the native found his homeland wartorn and its people weary and ravaged.

His assignment was to sift through countless German files and records, often from concentration camps and revealing the grizzly horrors of the war. He even translated an eye witness account from a man that later proved to be "one of the most incriminating documentations at the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials," he says. "It shocked the defendants and became the document most often cited to characterize the true nature of Nazism."

Though he was eager to return to his wife and children in the United States, the Army had a final task for Officer Von Rosenstiel. He was assigned to the staff of Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson, the chief American prosecutor during the Nuremberg Trials.

Specifically, Von Rosenstiel was assigned to interpret to defendants such as Hermann Goering in preparation for trial. Goering, credited with creating the Secret Police, which later became the Gestapo, was responsible for the mobilization of economic resources that drove Hitler's Third Reich. He was eventually sentenced to death, but committed suicide the night before his execution.

In all, 21 Nazi leaders were tried as war criminals at Nuremberg. Most were sentenced to death or life in prison.

Von Rosenstiel returned to America in 1946. His fascinating journey from a German soldier to an enemy alien to a U.S. officer who helped prosecute Nazi leaders remains a highly sought-after lecture in historical circles.

The incredible events of his life make his gifts back to UC all the more precious. He and his second wife, Anne, returned to the university last fall and brought with them a generous endowment for the department of history, as well as several hundred important books, periodicals, documents and photographs that Werner had collected both during the war and since. The vast collection is now housed on the third floor of UC's McMicken Hall in the Von Rosenstiel Reading Room for current and future generations to study.

"I collected all of these books over a very long life," he said during the room's dedication last September. "I felt that they were of particular interest to anybody who wants to concern themselves with how it came that we would get a Hitler. Perhaps they can also learn how not to do it."

Von Rosenstiel's book, "Tales of an American Soldier," is available in major bookstores.

Link:

"Tales of an American Soldier" at Amazon.com

Update: Werner Von Rosenstiel died in 2008. Read his obituary.

Past Issues

Past Issues