Tips from the top 'Risk-Takers'

Charles Luken

by Charles Luken, JD '76, Cincinnati mayor, survivor

Editor's note: In April 2001, Cincinnati experienced three days of rioting following the shooting of an unarmed black man by a white police officer. The incident triggered a four-day curfew imposed by Mayor Luken, a racial profiling lawsuit against the city and community activists' efforts to have entertainers and convention business boycott the city. Although Mayor Luken encountered much criticism, he was re-elected to his second consecutive term last November.

Instinct: When you are in a crisis -- and I have been in at least one -- it is best to go to your gut, to your basic understanding of people, of your city, then just do what you think is right. I think you have to rely on that instinct. And then things will usually work out for the best.

Police patrolling Over-the-Rhine to quell racial riots that brought the city and its mayor into the spotlight. Photo/Carrie Cochran/The News Record

Decisiveness: We have a city manager form of government, and I wish I had forgotten about that sooner and just stood up and taken charge. It took me a few days to get to that position, and that was really out of respect for the form of government. I can't say I did everything perfectly, but I did make a conscious decision to forget all the people pulling and tugging at my sleeve and just do what I thought was right. It doesn't always work out, but it did in this case.

Experience: We all develop experience in our professions. In my case, there were a few people, and I mean less than five, I consider true advisers. Their counsel was invaluable. And I believe that experience has taught me ...

Patience: When I say patience, I mean I could not solve the problem in an hour or a day, as much as I wanted to. But you need a kind of belief that if you're patient, things will improve.

Perseverance: One thing people said to me, besides "I’m praying for you," was "hang in there." And I think by "hang in there," they were saying, "We know you’re in a crisis. We know you are being blamed, but if you hang in there, people generally will give you credit for trying to do the right thing."

Charlie Luken served on Cincinnati City Council from 1981-84 and as mayor from 1984-90 and again from 1999 to the present. The UC grad was a news anchor for WLWT-TV from 1993-99.

UC alum Art Cohn has spent more than 20 years scouring the bottom of Lake Champlain looking for historic shipwrecks.

How to handle buried treasure

by Art Cohn, A&S '71, curator of sunken secrets

Identify your treasure. Lake Champlain has the largest collection of historical ships in the country. We have several hundred wooden ships reflecting every time period: Native American, French and British war ships from the 1750s, Revolutionary War ships, War of 1812 ships and ships of commerce up until 1920, including a horse ferry. A paddle boat powered by horses on a treadmill, the ferry is the only surviving example of that type of technology known to exist today. Some ships are mostly intact, some with masts still standing, because they've been in fresh water, instead of salt water.

Determine its value. This is the closest thing to going back in a time machine, to suddenly view a vessel from 200 years ago. A better understanding of the past is one of the tools we need to make a better world, and part of the tools in the tool bag are history and archaeology.

Just as we have historical buildings on land, we have archaeological sites underwater. These are finite resources that have extraordinary ability to teach us about human history. Therein lies the value and the threat. As technology has advanced so that we can now access things in any corner of the ocean, we are faced with decisions that will determine how much is left at the end of the century.

Think outside the box. "Underwater cultural heritage" is something our generation has defined as valuable. If it stems from public resources, then the public should have access to it. As part of our management approach to these public resources, we've developed an underwater park on the lake to make seven sites available to divers. It's a museum collection space, 500 square miles of cold storage for hundreds of wooden ships.

Evaluate the cost of raising the treasure. Last summer (2001), we raised 20 objects, including some cannon fragments from the Battle of Valcour Island (where Benedict Arnold commanded the American fleet in 1776). We are currently conserving them, at a cost of approximately $15,000, to go on public exhibit in May (2002).

Raising and conserving a whole ship, however, would cost millions. Right now, we're studying an intact Revolutionary War ship on the bottom of the lake -- looking at the options of leaving it where it is, repairing it, partially excavating it or raising, conserving and exhibiting it.

Decide on a course of action. We usually opt for leaving artifacts alone. In the past, many well-meaning, but disastrous, efforts were made to remove them, to get close to them because we loved them. But bringing them into the air de-stabilized them and led to their destruction.

Art Cohn is a sociologist, lawyer and professional diver who co-founded and directs the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum in Vermont. He pushed the state legislature to create Underwater Historic Preserves in 1975, testified to Congress in support of the Abandoned Shipwreck Act in '87 and most recently worked with the U.N. in developing an international shipwreck treaty.

Link:

Cramer poses in his dining room before "Blue," an abstract by Cincinnati's Jim Dine, one of his favorite contemporary artists. Photo/Philip Greenberg

Tips for investing in art,

cashing in on canvas

by Douglas Cramer, A&S '53, collector and philanthropist

My No. 1 tip: Don't. You should never buy art with an eye toward making money. The market is given to swings as wild as the stock market. I've bought artwork that was worth 10 percent of what I paid for it 10 years later. Then 10 years after that, it was worth 300 times what I paid.

Be brutally fair: Art should be looked at as something you want to live with. I have a lot of paintings I can't give away. Some still hang in my house even though people ask me why in the world I have held on to them. I still enjoy them.

Do a lot of work: If you are foolish enough to play the art market to make money, you've got to study what's gone on with the artist's work for past 50 years. Before making a commitment, be sure to see the artist's other works from different periods.

Buy a drawing first: I almost never buy a painting or a sculpture without first buying a drawing. You should get used to living with it.

Know the artist: Get to know the dealers; then the artists, if they are alive; and if possible, go to their studios. Most "hot" artists' shows are sold out before they open because people bought art in their studios. I recently bought a wonderful new artist's painting from a sketch he'd done. He hadn't even completed the painting, but I hadn't been able to buy any of his work for three years, and I engaged in a heated battle with four other collectors to get this one.

When artists know you, that makes an enormous difference. It's not by chance that my closest personal friends have included Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns, Ed Ruscha, Ellsworth Kelly and Jim Dine (who studied art at UC in the late '50s).

It's not easy: Regardless of the skill, dedication, energy and money you invest, you can still make mistakes. But with art, at least you get to live with it.

Co-producer of Broadway's "Tale of the Allergist's Wife," Douglas Cramer is a New York Museum of Modern Art trustee, a founder and former president of the L.A. Museum of Contemporary Art, a philanthropist who gave the Cincinnati Art Museum $6 million worth of art and a Hollywood producer who spent 30 years creating and developing 90 TV movies, the first miniseries ("QB VII") and series such as "The Love Boat" and "Mission Impossible."

Photo/courtesy of Jean Ellis

How to get to the top

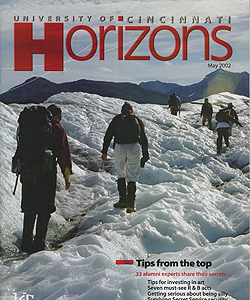

by Jean Ellis, A&S '69, MD '76, mountaineer

1. Endurance is the key. Climbing an 8,000-meter peak is a 100-day trip. So you have to pace yourself, and you also have to have a little luck. But this is definitely an endurance test.

2. Plan on weight loss. Usually I gain a little weight before a trip. My regular weight is 145. I put on 10 pounds and dropped from 155 to 117 (38 pounds) on one expedition.

3. Stay healthy. The body doesn't heal as well at 20,000-plus feet.

4. Expect a tremendous psychological effect. Certain days you are as high as a kite. But other days you are depressed and fighting back tears. You have mail call just like in the military. If your buddies all get mail and you don't, that can be tough.

5. Down is king. Down bags. One-piece down suits. You can cut corners on the undergarments and the polypropylene, but don't cut corners on your outergear. Bags and boots, too; go for the quality. There is nothing worse than being out in the middle of nowhere and freezing.

UC alum Jean Ellis, 55, qualified as a marathoner for the 1980 Olympic trials, but was crushed when the U.S. boycotted the Moscow games. He followed the call of a medical journal ad to trek in the Himalayan Mountains of Nepal. Twice he attempted Everest and was turned back with frostbitten hands. The emergency medical physician still goes on a "major climb" every year and became the first African American to summit an 8,000-meter peak in 1996 when he climbed to the top of Cho Oyu (pictured), the world's sixth highest mountain.

Past Issues

Past Issues