Welcome to life at Paramount Studios

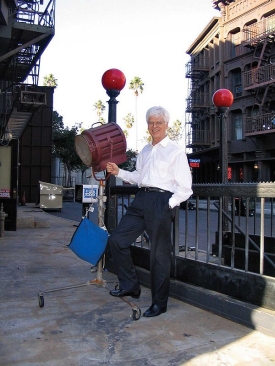

When Tom Bruehl heads from his Hollywood office in the Mae West Building to the nearby sound stage, he may pass through the streets of Brooklyn. Or maybe Greenwich Village. Or perhaps Chicago.

Well … no. Chicago is a few blocks out of his way.

Bruehl, CCM '68, works on the sprawling 50-acre lot of Paramount Studios, the last remaining movie studio in Hollywood. The other studios have migrated over the hill to Burbank, but Paramount still consumes 26 square blocks in the middle of downtown, where it accommodates, among other things, 30 sound stages, 140 editing rooms, 3 million square feet of office space, a submersible parking lot for water scenes, a Foley stage for creating sound effects, two theaters appropriate for premieres, three smaller theaters and nine exterior sets.

Right behind Bruehl's office are the back-lot sets that recreate famous downtown atmospheres, including fake alleyways, a high-rise office building to mimic a financial district (as seen in "Mission Impossible III"), a Greenwich Village coffee shop (near Ally McBeal's famous stoop), a subway entrance (seen in Madonna's Gap commercial) and brick row houses evocative of Boston, London or Washington, D.C. (used in scenes from "Monk" and "Seinfeld").

It's not a typical work environment, but Bruehl doesn't have a typical job. As Paramount's senior vice president for technical operations, he oversees a division that he was hired to create in 1982.

"I'm getting a chance to really play at the highest end of the entertainment industry," he states with an air that indicates he's still impressed that he made it there. "With five studios in Los Angeles, that basically means there are about four other people in the world who have my job. … Having said that, I'll probably get fired tomorrow," he adds with a grin.

The area of "technical operations" may sound a little abstract, and the owner of the title concurs. "It's hard to explain what that means," he confesses. "If you find someone with the same title at a different studio, it will be a different job. There's no unanimity of opinion on it."

When Tom Bruehl heads from his Hollywood office in the Mae West Building to the nearby sound stage, he may pass through the streets of Brooklyn. Or maybe Greenwich Village. Or perhaps Chicago.

Well … no. Chicago is a few blocks out of his way.

Bruehl, CCM '68, works on the sprawling 50-acre lot of Paramount Studios, the last remaining movie studio in Hollywood. The other studios have migrated over the hill to Burbank, but Paramount still consumes 26 square blocks in the middle of downtown, where it accommodates, among other things, 30 sound stages, 140 editing rooms, 3 million square feet of office space, a submersible parking lot for water scenes, a Foley stage for creating sound effects, two theaters appropriate for premieres, three smaller theaters and nine exterior sets.

Right behind Bruehl's office are the back-lot sets that recreate famous downtown atmospheres, including fake alleyways, a high-rise office building to mimic a financial district (as seen in "Mission Impossible III"), a Greenwich Village coffee shop (near Ally McBeal's famous stoop), a subway entrance (seen in Madonna's Gap commercial) and brick row houses evocative of Boston, London or Washington, D.C. (used in scenes from "Monk" and "Seinfeld").

It's not a typical work environment, but Bruehl doesn't have a typical job. As Paramount's senior vice president for technical operations, he oversees a division that he was hired to create in 1982.

"I'm getting a chance to really play at the highest end of the entertainment industry," he states with an air that indicates he's still impressed that he made it there. "With five studios in Los Angeles, that basically means there are about four other people in the world who have my job. … Having said that, I'll probably get fired tomorrow," he adds with a grin.

The area of "technical operations" may sound a little abstract, and the owner of the title concurs. "It's hard to explain what that means," he confesses. "If you find someone with the same title at a different studio, it will be a different job. There's no unanimity of opinion on it."

At Paramount, his division encompasses a wide range of projects. Consequently, he attends a weekly meeting regarding the status of all pictures in production. One day last fall, Paramount had 18 pictures in post-production. A small sampling of his division's responsibilities follows:

- Daily shootings of "Entertainment Tonight" with Mary Hart, "The Insider" with Pat O'Brien and "Dr. Phil," all for first-run syndication

- Reproducing movies and TV shows to be sold around the world, including "Love Boat" to Croatia, "Gunsmoke" to Finland and "I Love Lucy" to 40 different countries

- Replacing audio tracks with recordings done on stage

The last area brought actress Jennifer Hudson to Paramount in the fall to replace the tracks of her singing in "Dream Girls." "She was very new to this," Bruehl says of the singer who subsequently won an Oscar for her supporting role, "but after about half a day, she really got the hang of it. There's a knack to it. Some actors are certainly better at it than others."

Most movies shot on location have poor sound quality due to the environment — planes, traffic and people making noise. Afterward, actors are called in to the Automated Dialog Replacement stage where they lip-synch their own dialog or songs into a microphone while watching a monitor. Multiple takes are always required to obtain the precision needed, then the new tracks are edited into the film. In some movies, as much as 80 percent of the dialogue gets replaced, Bruehl says.

Dialog, of course, isn't the only audio track to be replaced. On the Foley stage, live sound effects are matched to every single action on screen, as well as some off-screen activities.

"If you've got an outdoor scene where a person swings a bat and hits a baseball, you're not going to get that sound effect on location," Bruehl explains. "Someone has to create that sound on a stage, then match it up, so that when you see it and hear it in the movie, it's plausible.

"If you were to look at one of these Foley stages, it looks like a garage sale gone bad," he jokes. "These are junky, messy places, and the junkier and messier they are, the better."

That's because Foley artists need to replicate sounds of anything imaginable, from rustling clothes to explosions to footsteps. The latter requires about 15 different surfaces to be embedded in the stage floor, where "Foley walkers" use such things as leather, cleats or high heels to reproduce the sounds of skipping, stomping or strolling across concrete, carpeting or ceramic tile. "It all sounds different," Bruehl says. "And it's kind of fun."

"Fun" is the way he often describes his work. He truly enjoys the variety he faces, as well as the challenges presented by an ever-transforming technology — though he claims he's not a technical person.

Nevertheless, Bruehl has demonstrated a remarkable grasp of the scientific side of the business, expertise he eagerly passes along to Paramount's new senior executives. "I've always had the ability to explain stuff in human terms," he says. "I can't delve into the technology, but I can grasp what it does and what the problems are. So I can translate the issues to chief financial officers, operating officers and the like." He is, however, technical enough that he worked on patents for a special-effects process in the late '80s. And today, he is excited over new 3-D developments and the enormous possibilities posed by digital cameras.

"Digital cinema is so new that we're all still learning it and writing the rules," he says. "In a way, I've never stopped going to school. That's the fun part."

Fun? Of course, it is. So what's "not so fun" about his job?

When pressed, he concedes, "Dealing with the creative persona is the most challenging." Then he backs off, adding, "But I'm comfortable with that. I can empathize when somebody in a creative position is really frustrated.

"As Buckminster Fuller once said, 'True progress relies upon the unreasonable man.' Every once in a while, you need somebody to say, 'Why can't we?' Then you say, 'OK, maybe we can.'"

Bruehl is used to seeing how far he can go. As a broadcasting student at the College-Conservatory of Music in the mid-60s, he worked professionally off campus all four years — the first year as a rock 'n' roll DJ on a local radio station, then the following three years as a TV announcer, first for Channel 9, then 5.

His professional experience as a student solidified his career choice of film over radio, and his education was invaluable, he says. After graduation, however, he wanted more. "I just wasn't ready to settle at that point. I was either going to go to New York or L.A. to see what this was all about. And it's a lot warmer out here."

He actually put a little more thought into his destination than the thermometer would indicate. Because he knew New York was oriented more to news and commercials, L.A.'s focus on entertainment was more appealing to him.

California also had another attraction — UCLA's television film school. He was immediately accepted into the master's program and also landed a job with a local NBC station working on a game show. He had barely completed his coursework when the Army drafted him. Two years later, he returned to civilian life and, once again, faced the location dilemma.

In less of a hurry to make up his mind this time, he worked for a couple of years in New York and Chicago. That's where the weather actually did became a deciding factor.

"I stepped off a Chicago curb one January and went up to my knees in slush," he vividly recalls. "I thought. 'This is crazy.' So I called a friend in L.A. and said, 'I need to borrow your extra bedroom for a while.' Two days later, I was here."

Three months later, he was a production manager for a couple of sitcoms that were being shot at KTLA studios, including Norman Lear's soap opera spoof "Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman." "That was a strange one," he says. "I have never worked on a show since then that had that aura about it. It was a good thing I was young, because I could roll with the punches. It was exceptionally fun."

By the mid '70s, his reputation for shooting video led Warner Bros. Studio to recruit him to run its video division. After a few years, he wanted to learn more about feature films, so he headed to a motion-picture lab, post-production company. There he learned enough that within a few years Paramount recruited him to start its videotape division "from scratch," as he puts it. "It's still going strong and expanding," he says proudly.

In many ways, his career has exceeded his early dreams. "This isn't what I thought I'd be doing when I came out here," he admits. "But I found myself with the gift of blarney, an aptitude for management and good sensibilities. And I can smell BS."

All those traits, mixed with a never-ending curiosity, a natural inclination to network and a diligence for hard work, gave him an impressive reputation around town. So impressive, in fact, that he never had to apply for a single studio job. He was always recruited.

Furthermore, he was always recruited to implement new projects, which was a bonus for him. "The good part about being asked to start something new is that I've never had anyone looking over my shoulder, saying, 'Why don't you do it like Bob did it?' I guess the people who follow me will get that."

He's in no hurry to retire, but he does predict that one day he'll return to his early career choices. "I'd like to go back into announcing. Maybe voice-overs and commercials. I enjoyed it, and I was good at it. That's something to do when you don't have to worry about making a living."

Related article

Bruehl's motion picture insights

LINK

Paramount Studios

Issue Archive

Issue Archive