Reached for the sky

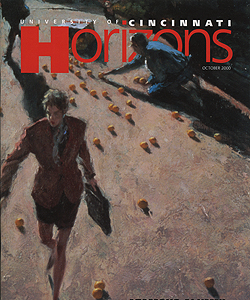

Entrepreneurs Leslie and Bruce Eichner. Photo/C.W. Griffin, The Miami Herald

by Mary Niehaus

"My plan! My plan!" It was 1973. An agonized Bruce Eichner, JD '69, was down on his hands and knees in front of the five-story brownstone he was rehabbing in Brooklyn, trying to piece together chunks of broken Sheetrock. A workman had accidentally trashed the building's remodeling plan. How was he to know that Eichner begged an architect to sketch a design on Sheetrock because he had no money for standard construction drawings?

Although things looked grim for the upstart developer, a struggling government lawyer who was itching to launch a new career, Eichner was not about to give up. After all, he had spent six months schmoozing with neighborhood real estate agents to learn about the business, four months every Saturday and Sunday coaxing the elderly owner into selling and countless hours convincing three separate banks to lend him the $10,000 down payment.

Today, leaning comfortably across an enormous round table in his 14th floor office suite above Madison Avenue -- complete with a spectacular Manhattan view -- the affable New York/Miami property developer can chuckle about his rocky entry into the world of high-stakes, high-rise real estate. His 27 years of exploring all the possibilities, in order to construct the most advantageous deal, find him remarkably down to earth.

Without Bruce Eichner the Big Apple's skyline would not be the same. His handiwork includes the sleek 70-story Cityspire near Carnegie Hall, the triangular-crested 1540 Broadway building on Times Square (now the Bertelsmann), several condominium high rises and New York's first and only luxury timeshare, The Manhattan Club at Seventh and 56th.

For example, the New York native was one of the first to build condominiums in the city, a departure from its traditional co-op apartments. Uncanny in his ability to spot trends, the University of Cincinnati law grad realized in the early '70s that rents were beginning to soar. He did the math and saw that he could sell condos to renters for virtually the same amount they paid to rent. So he did.

Eichner was the first to invite grocery stores to set up shop in the basement of his condo buildings, the Royale on Third Avenue and the Boulevard on Broadway. Residents loved the convenience of underground supermarkets, and merchants enjoyed prime space at good prices.

Cityspire, the first "mixed-use" skyscraper in New York, was an Eichner innovation. Restricting offices and retail to the less-desirable lower floors, he built apartments at the 25th level and up so residents could enjoy the view and avoid street noise. It is the only mixed-use New York skyscraper with energy-efficient clear glass windows, as well.

Because every added floor increases a building's value, Eichner yearned to make Cityspire a 70-story structure, rather than the authorized 30 floors. Instead of hounding City Hall for more "air rights," he approached opera diva Beverly Sills for help. The New York City Opera was a tenant of the neighboring building, and its theater had a painfully narrow stage.

"So, I said, 'Look, when I build next door, I'll build an addition that will allow you to widen the stage and create additional facilities.' So, I got Beverly Sills, the opera and the nonprofits to sing sonatas and piccatas for me at City Hall."

With the support of his neighbors in the performing arts, developer Eichner got the construction permission. He said thank-you to the arts with a $6 million gift.

So where did this fast-talking charmer get his entrepreneurial know-how? He began with no track record as a builder or businessman, no education in property development or economics, no family wealth to draw upon and no "old boys network" to smooth his way into the Big Apple's financial and political heart.

"What I've always tried to do," Eichner insists, "is to put myself in the position of the other person, to recognize what is going to be the nature of the opposition. Then, essentially, I try to offer something a little different.

"And, because I grew up in government, I realized that virtually every project I undertook from 1977 on was interwoven with the government approval process: tax abatements, tax incentives, job-related options. I came to understand that if you used the tax abatement program intelligently when you renovated a building, you could wipe out the real estate taxes for 12 or perhaps as many as 20 years."

"When I built my first 40-story high-rise, there was something called a 'plaza bonus,'" he points out. "You could make a building 20 percent taller if you built a plaza on the south-facing side." Since one of his sites was not suitable for a southern plaza, he petitioned the planning commission to give him credit for a north-facing plaza. It worked: A north plaza was better than no plaza.

Intellectually, Eichner seems to be in perpetual motion, exuding a boyish enthusiasm that belies his 55 years. A self-confessed "contrarian," he does not hesitate to take the opposing point of view to conventional wisdom. He says that being a "horizontal thinker" is his advantage, that it inspires creativity and experimentation.

A few years ago, UC's College of Law asked the successful developer to come to campus to address the graduating class. The invitation caught Eichner by surprise. He was sure the dean had confused him with someone else.

Entrepreneur Eichner asked the UC law school dean if they kept records at the school. "He said, 'Sure. Why do you ask?' I said, 'Dean, let me be very candid with you, because I think there's been a mistake. I graduated dead last in my class at UC!'

"'Well, we were aware that you had an undistinguished academic record,' he said. "I laughed and told him my father (a college dean of men) would greatly appreciate that description. He referred to it as my intellectual hobo expedition."

Nevertheless, it was Ian Bruce Eichner the UC students wanted to hear. So he came.

"The fact that you go to law school does not necessarily mean that either you need to be a lawyer or that your strengths and skills are primarily in the law," he told the graduates. "You may not like it. You may not be particularly good at it. But you have been taught how to analyze issues. You've been taught a certain type of thought process. That can be excellent training for something totally unrelated."

Even with all his energy and talent, Eichner could not avoid some bumpy times. He lost millions when the New York real estate market crashed in the 1980s. That hurt. A lot.

But the inveterate optimist bounced back. In addition to his thriving Manhattan timeshare, a glamorous Florida high-rise development has begun on "the last major oceanfront piece of land at the tip of Miami Beach" and a soon-to-be-launched dot.com is expected to "revolutionize the lawyering business in the United States."

The trim, athletic multimillionaire, whose conversation is punctuated with one-liners, seems totally at ease with who he is today: president of the Continuum Company, working in partnership with his wife Leslie, a former banker, and very proud father of their 12- and 14-year-old daughters.

"I think I realized a long time ago that there's only one thing that's in my control: my level of effort," he says. "I do not control whether interest rates go to 21 percent in the shade. I don't control whether Pakistan's going to invade India or if the stock market drops 3,000 points.

"I've tried to explain this to my two girls," the UC alum confides. "When you make a lot of money, guess what? You're not a genius. There are lots of things that contributed to that. And if you take a fall, it's not personal.

"If you want a guarantee," he grins, "you have to stay home."

Links:

Eichner featured in "High Rise" book

Past Issues

Past Issues