Stylish and comfortable

A monochromatic uniform by alumnus Herman pleased employees of the JetBlue airline. Photo/courtesy Stan Herman Studio

by Mary Niehaus

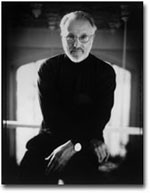

A wall of windows overlooks Manhattan's Bryant Park, flooding the design studio with soft light. Pale walls, rising from light oak flooring, are crowned with a subtle classic frieze. Two assistants lean on their drawing tables, engrossed in work, like monks bent over illuminated manuscripts. Classical music wafts softly through the minimally furnished space. All is serene in the eighth floor aerie, awaiting the return of fashion virtuoso Stan Herman, DAAP '50.

The quiet, light-washed studio at 40th and Sixth Streets, the locus of Herman's work for the past 25 years, breaks into cheerful pandemonium when the designer arrives. Voices tangle as messages and questions fly through the air. The telephone jangles. Herman's big black poodle, Mozart, barks sharply to be noticed by his master, who dotes on the wooly canine.

There was a time, before Herman became a three-time Coty Fashion Critics Award winner and an established professional, when his return to a design studio seemed unlikely. At the end of the 1950s, Herman quit the fashion business.

After several years as an apprentice designer in New York City, the talented UC alumnus was stymied. He kept getting fired. His work, he was told, was not "right" for the company's clients. He walked away and rather quickly was hired as a singer-dancer-actor on Broadway. After all, the former University of Cincinnati Mummer's first job as a UC student had been on a kind of stage.

Photo/courtesy of Stan Herman Studio

"It's true. My first job was pushing a swing in the window of Gidding's (former Cincinnati high fashion store) for a pre-Easter promotion," Herman remembers. "There was a girl in a dress on the swing. I almost pushed her through the plate glass!" he chuckles.

Had the handsome young designer permanently defected from the industry, America's understanding of popular fashion would be much different. No Stan Herman ultra cushy chenille bathrobes and comfy lounge wear. No luxurious sweaters and scarves. No stuffed chenille "Nubbies" animals and no Chenille perfume to tempt shoppers on the QVC cable network.

Celebrating his seventh anniversary on QVC this year, the enthusiastic Herman charms viewers each time he appears. They buy up his work faster than any other QVC designer's.

Without Herman at his design board, hundreds of thousands of workers around the world would have missed a chance to wear comfortable, stylish uniforms -- "real clothes" that look and feel good. Among the companies he has dressed are FedEx, McDonald's, New York's Le Parker Meridien hotel, Las Vegas casino-hotels like the MGM Grand and the Monte Carlo, as well as airlines like TWA and United and Amtrack's Acela bullet trains.

If the elegant Herman, still handsome in carefully trimmed white hair and beard, had left New York in the early years, the Mr. Mort fashion house would have faltered sooner than it did. As a designer, and later as the company's president, Stan Herman earned a 1965 Coty Young Designer Award for fresh ready-to-wear and a 1969 Coty for a women's wear collection. He came to be known as "the people's designer" because of his commitment to producing "good clothing at a price," rather than expensive couture.

The Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA) most likely would have kept its rather straightlaced and snobby reputation, without Herman's charismatic leadership. Now in his ninth year as president, he has helped the council evolve into an important force in political, business and artistic arenas.

"I think I'm fairly well liked," the Korean War veteran says. "People trust me. I'm not a threat to Tommy (Hilfiger) or Ralph (Lauren) or Calvin (Klein) or Donna (Karan) because I'm doing different work. I've designed just about everything. I seem to be able always to find a niche for myself."

Through CFDA, the energetic leader developed the "7th on Sixth" semiannual fashion shows, which give designers a central venue for showing their new collections to fashion editors and buyers. CFDA's annual fashion awards gala, held each June at Lincoln Center, is another hot-ticket event that attracts celebrities from around the globe.

"This is a very busy council," the president confirms. "It has done a lot of work to support research on breast cancer, ovarian cancer and AIDS. Each time we've held our '7th on Sale' benefit it raises $4-$5 million."

Herman's knack for leadership is evident from the 1950 UC yearbook: president of the Applied Arts Tribunal and prior of Sigma Alpha Mu fraternity. "When I went to the university there were very few out-of-towners, so it was an unusual thing for me, an outsider, to become president of my fraternity," he observes. Convincing the "Sammies" to move their Avondale frat house to Clifton Avenue, nearer the UC campus, is one of his most satisfying achievements.

"I made a lot of good friends, some wonderful friends," the gregarious Herman muses. "Many of them are gone, now. There are people who call me, who remember me from the past. Cincinnati pops up in my life every so often."

In 1998, it was his college that called Stan Herman to be the honored guest at DAAP's annual fashion show and honors night. The posh event at Cincinnati's Convention Center benefited UC's design program. He has lectured at his alma mater and in several other prominent design schools around the world.

The forthright designer, who grew up in a small town in New Jersey, is glad he earned a degree at UC, rather than attending a vocational college. "It helped me," Herman says. "It made me a better person, gave me broader perspectives."

"I chose Cincinnati because I wanted to be in a city that had some cultural roots," he says. "It had a great symphony orchestra, an art museum, a great reputation for being a cultural Midwestern city. And of course I found it so pretty. It looked like an old European town to me ... and it still does."

Today, Herman genuinely enjoys being a New Yorker. He serves on a number of prominent boards: the Richard Tucker Foundation, the Midtown Manhattan Community, the Bryant Park Restoration, the Fashion Bid and the Gay Men's Health Classic (an organization for AIDS care, education and advocacy). "I've been a person who puts his money where his mouth is when it comes to New York," the designer declares.

The Tucker Foundation, which nurtures careers of young opera singers, is close to his heart. Herman studied opera for several years, singing lead tenor roles in "La Boheme" and "Die Fledermaus" at New York's semi-professional Amato opera house.

During his brief hiatus from the fashion business, of course, singing was essential to his show business persona. "I got into a Broadway show called 'La Plume de ma Tante' for six months, and then I was supposed to go on the road with Anna Maria Albergetti and Jerry Orbach in 'Irma La Douce,'" he says. But he declined the road show, which meant that he was available when a designer friend begged his help.

"I was in a Broadway show at night, and I had my days free except for matinees," fashion designer Stan Herman recalls. "So I came over to Seventh Avenue and designed this collection for a friend. Because I was in a show, I didn't worry about getting fired. I just did it.

"It was a complete success! Women's Wear Daily declared: 'A star is born.'"

Herman finally realized that he had been designing "young clothes" all along, which is why the older companies, who catered to mature women, had rejected his work. For the next six months, he continued to be an understudy in "La Plume" at night and a designer for Junior Forum during the day. Then he was recruited to work for Mr. Mort, an affiliation that lasted until Herman went to free-lance in the early '70s. He received his third Coty Fashion Award in 1975, for lingerie design.

The fashion capital has been an energizing force for Herman. "I love New York," the he insists. "It's a very difficult city. A tough city. But it's also a fair city.

"I really think, in order to be creative, unless you are a genius or unless you can be creative in a toilet bowl, that this is the town to do it."

Past Issues

Past Issues