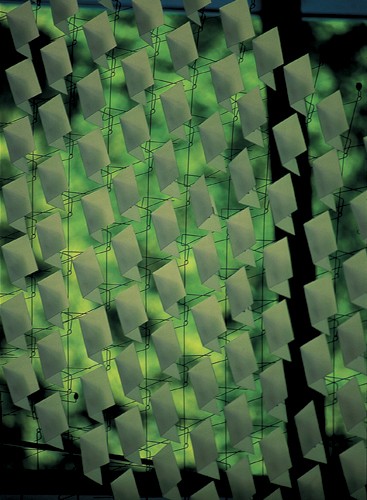

Measuring the human impact of UC's architectural renaissance

by John Bach

photos by Bob Flischel

Can you build community using bricks and mortar?

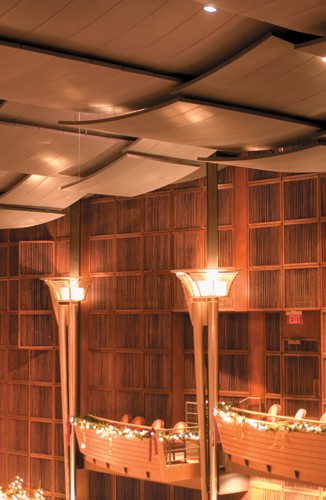

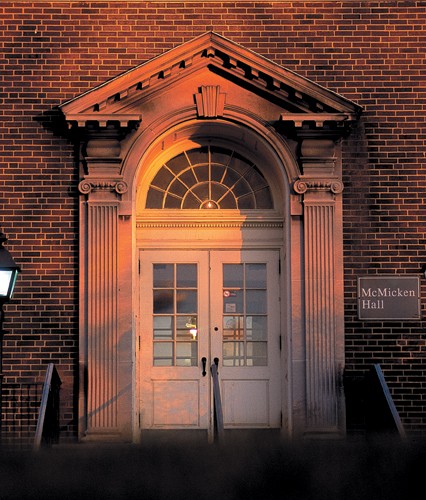

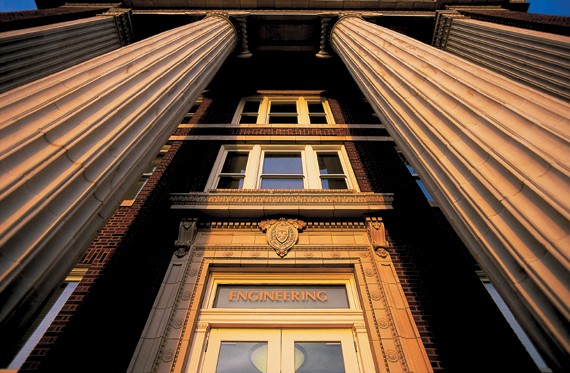

Absolutely. As the University of Cincinnati wraps up a long 15-year campaign to make over the Uptown Campus, it is clear that the effort is yielding more than just a physical transformation. The new campus may also be contributing to a shift in the culture and, perhaps, even changing the way members of this community think and relate to one another. The campus reformation -- a capital investment exceeding $1.2 billion -- has not gone unnoticed nationally.

Places Magazine dubbed UC "an international cultural destination." In hailing the university's conversion from "a nondescript, slipshod building complex," the magazine joins the ranks of national media such as the New York Times, the Chicago Tribune and the Washington Post, all of which have heaped praise on UC's signature architecture and greener campus.

But to what end? Was international acclaim the purpose? Does UC's urban renewal further education? And does the more attractive university setting actually attract more? Administrators are counting on the more stimulating, architecturally rich campus to improve the learning environment as well as boost the recruitment of world-class students and faculty. If initial results are any indication, they are right.

In the fall of 2007, for the first time, UC was forced to create a waiting list for incoming freshmen because the volume of applications was so large. Michaele Pride, director of UC's architecture and interior design programs at DAAP, confirms that the intrigue with the physical campus has become an essential marketing tool.

Beyond recruiting, architects and planners maintain that the spaces hosting collegiate experiences have a profound impact on students during their formative years, affecting both who they are and who they will one day become.

Issue Archive

Issue Archive