By John Bach

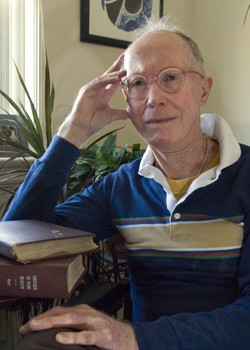

48 years and counting for philosophy professor

Rollin Workman warns that his story will "turn out to be very dull."

After all, who wants to know about an 80-year-old professor emeritus of philosophy who can't stop volunteering at the university from which he retired 18 years ago? Particularly one who admits the academy is the closest thing he has to a family?

He thinks no one will be compelled by a guy born in 1926 who still runs nine miles a week and likes the feeling of jogging barefoot on Nippert Stadium's turf. Nor will they be interested that he doesn't watch television and doesn't care about the Internet, yet pines for a few free hours to contemplate complex philosophical arguments.

Though he retired in 1988, Rollin Workman's daily routine hasn't changed much over the last 48 years. The spry PhD still walks from his home in Clifton to UC nearly every day. Instead of coming to teach, as he did for 30 years, Workman volunteers in the McMicken College of Arts and Sciences advising office. For the first decade of retirement, advising was a way to maintain a connection with students, which he believes keeps him "younger in attitude."

These days, however, advising requires computer work, and his macular degeneration won't allow it, at least not without using his magnifying glass. And that's too slow. So Rollin files, and that's something he can do at his own pace.

Still, he reports to the first floor of McMicken nearly every workday, and he continues to profess the same Calvinist approach to life that more than 30,000 former UC students came to recognize in his lecturing years.

"I suppose if there is any philosophy by which I live my life, it is the old stoic maxim, 'Do your duty though the heavens fall,'" Workman says. "The first priority is carrying out the responsibilities of whatever position you have. And if there is any time left for pleasure and enjoyment, well, OK. If there isn't, well bear with it."

Workman's utilitarian style stands out for former student and graduate assistant Richard Friedman now senior assistant A&S dean, as he recalls his professor and friend's dedication to teaching the course, "Man and Ideas."

"Many of us were taken aback by his unbridled thoroughness of presentation on a subject matter that had many a political and social implication," says Friedman, A&S '68. "His sense of fairness on each and every topic was more than impressive. It was clear that he wanted you to become engaged in the seriousness of it all. It was not just a course for him, but a way of life."

Friedman says Workman would invite students who were unsatisfied with their exam scores to his office to "argue for more points." "I remember a rather large handmade sign that he displayed that read, 'No points will be given for thoughts that were in your mind but not on your paper when you wrote your exam.'"

Hired by the College of Arts and Sciences in 1958, Workman spent the bulk of his professorial career teaching the "Man and Ideas" survey course that drew about 300 students into his class each quarter (except for the late '60s when more than 900 students packed into his Wilson Auditorium classroom). By the early '70s, the course name evolved into the more inclusive "Moral and Political Ideas," which he taught until his retirement.

Workman admits he stopped teaching the course because he grew weary of grading hundreds of essays. Still, he allowed himself to retire only when he knew there was something else he could continue doing at the university. And working in advising for the college was perfect.

It was a way to stay in touch with the career that saw him win both the Dolly Cohen Award for Excellence in Teaching and the George Barbour Award for Furthering Good Faculty-Student Relations. He was the first member of the faculty to win both distinctions.

"Observing people who had retired," Workman recalls, "they seemed to be terribly bored. I'd always get these stories of people who retired to Florida, and they couldn't figure out anything to do to give them enjoyment. So they tensed up, and they had heart attacks and they died. So I figured I'd better find something to occupy my time that I considered to be useful."

In addition to his volunteer work with A&S, he has been an advocate for many student groups including Omicron Delta Kappa as faculty secretary and Phi Beta Kappa as a faculty adviser. The students, he often preached, "must be served."

These days, the professor belongs to a literary group and takes it upon himself to keep the club roster as well as index their weekly readings. Plus, he teaches a course, "Ideas in Philosophy" for UC's Institute for Learning in Retirement.

It all leaves very little time for his one true passion of trying to understand the mind of his favorite philosopher, Immanuel Kant, who died in 1804.

"I'm lucky if I can find two or three hours a week that I can actually spend time on Kant," he says. "I'm usually fixated on some small detail of Kant's argument. I regard him as sort of like a murder mystery."

You can call Workman's 48 years of service to UC "dedication," but he'd prefer you didn't.

"I'd rather think of it as just selfishness because I enjoy it," he says. "I just always considered the university kind of my home, and it allows me to stay home. Besides if I missed too many days, how would I know what's happening around campus?"

Issue Archive

Issue Archive