African American heritage at UC

Alumna Georgia Beasley. Photo/Lisa Ventre

Squaring her shoulders and setting her jaw, young Georgia Beasley refused. Flat out refused.

It didn't matter that she was missing lessons that were part of her curriculum. It didn't matter that she was her sorority's first scholarship recipient and that she always followed the rules. These rules were unfair. Worse yet, they were insulting. So she refused to follow them.

As a future teacher in the University of Cincinnati's College of Home Economics, Georgia was required to take a physical education course, which included swimming lessons on Tuesdays. Actually, she wanted swimming lessons. On Tuesdays, that is.

But the problem was Georgia was banned from the pool on Tuesdays. She could only plunge her black body into the water on Fridays, the day reserved for the "coloreds" to use the university swimming pool.

The memory has haunted her. Enough that she readily speaks of it nearly 80 years later. "So many places we weren't welcome," she recalls. "It was known that we weren't wanted at UC."

While students may know the textbook details of segregation, they rarely relate it to their daily lives, failing to realize that many of the benefits they have today came from courageous students who refused to be overlooked, students who stood their ground on a campus that was far from just and in a society that condoned it.

To honor some of UC's alumni who have been "pioneers in the black community for the advancement of education," the university named 18 of them "Living Legends," representing the last nine decades. In November, they gathered on campus for a Living Legends Symposium at the African American Cultural and Research Center. Although poor health kept two of them from attending, they joined the event via large-screen video interviews. By the end of the program, students would learn of their predecessors' struggles for things as basic as the very building in which they were meeting.

Searching for alumni from each decade was not easy, as Eric Abercrumbie, PhD (A&S) '87, UC director of Ethnic Programs and Services, soon found out. Until the 1950s, race was not listed on student records. "Search" was indeed a key word here.

Yet as the millennium drew to a close, the effort became a passion for him. Alumni who endured prejudice and responded by demanding change, he said, were "trailblazers" who paved the way for the African American Studies program, the African American Cultural and Research Center (of which he is also the director) and other breakthroughs on campus and in society. "There's been a lot of blood, sweat and tears, as well as joy, in this century," he commented.

1920s and '30s

UC acknowledges the reality that African Americans on campus have faced many obstacles for many generations. "I was practically the only African American in any of my classes," said Georgia Beasley, Ed '25. "Friends would want me to go to their house, but their parents didn't want me. One white student, Dorothy Gillespie, worked with us and really wanted to have an interracial group on campus, but she couldn't get anyone else to go along with her."

One of Beasley's disappointments was being unable to join the UC choral group. It was a familiar exclusion. At Withrow High School, she had rehearsed regularly with the glee club, but could never take the stage with them.

By the '30s, blacks at UC occasionally made it in the chorus of main-campus troupes, but little else had changed. "There were no black students in any organizations," said Donald Spencer, A&S '36, Ed '37, MEd '40, at the symposium.

Numbering only about 100 students, the African Americans on campus quickly disappeared into the student body of 11,000. Alumni say that a sense of isolation consumed the group. "When I first came to UC, black students didn't meet each other," Spencer said. "We came to school, went to work, went home to eat and sleep, and started over again." But college was supposed to be more than that. He knew it. He believed it. So he did something about it. In fact, he did a lot.

One of the moves deserving of a Living Legend title was the formation of a black student organization, "Quadres," which had four goals: to promote high ideals and scholarship, foster cultural enterprise, establish contacts to aid social life, and encourage interracial harmony and participation on campus.

Disgusted by the discrimination shown by his colleagues, classics professor Malcolm McGregor agreed to serve as the group's faculty adviser. "At the end of two years, we had black students in everything," Spencer said, "the band, the women's tribunal and the men's senate."

Of course, "everything" is a relative term. Much remained to be done: Proms were often held at locations that barred blacks. Blacks were restricted from living in Memorial Hall, UC's only dorm. They were denied admission into the engineering and business colleges, based upon the understanding that co-op employers would not hire them. And student council was bleakly white.

1940s and '50s

Quadres attempted to change the student-council situation in '42 by putting Willard Stargel, a popular basketball and football player, on the ballot. Although he lost, his effort showed that black students were unwilling to simply accept the unacceptable.

In '46, Stargel again gave the African American population reason to rally after returning from the armed forces to rejoin the football team. It was a memorable year with the Bearcats opening the season with an upset of Big Ten champ Indiana, finishing with an 8-2 record and receiving a bid to play in the Sun Bowl in El Paso.

Willard Stargel from the "Personalities on Campus" section of the 1947 UC yearbook, "Cincinnatian."

Unfortunately, other memories turned into nightmares. Stargel had to sit out the Kentucky game because opponents refused to take the field with him, then Sun Bowl officials barred UC from playing with him.

Enraged, UC President Raymond Walters asked the Board of Trustees to refuse the bowl bid for "ethical and patriotic reasons." A power struggle ensued, and local citizens began choosing sides. Walters lost, the Bearcats won, and the university suffered.

Through it all, black fraternities and sororities began to grow in popularity, and the need for Quadres subsided, allowing it to quietly fade away by the end of the decade. In the '50s, as Moss White remembered, the student union was a big place for blacks to hang out and socialize.

Nevertheless, it was not a time of contentment. "It was a time of searching," said White, Ed '59, MEd '63, retired director of Cincinnati Public Schools. "We found there were some white kids trying to reach out to us in the '50s, but we weren't that happy over it because we were angry.

"We were really trying to seek our own identity because we were not sure we knew which way we were going. But we knew there was something better out there than what they had presented to us in the past."

1960s and '70s

The early '60s welcomed one of the most visible signs of integration; blacks were admitted into the dorms. Still, tensions continued to grow.

"It was the beginning of the civil rights movement," said Cheryl Grant, A&S '66, JD '73, Hamilton County Municipal Court judge. "You have to understand that white fraternities and sororities got special treatment, and it was important for black students to work toward social equality. There was an effort to stand up to things this campus did to rob you of your dignity."

Within a few years, much started happening. In the middle of most of it was Dwight Tillery, A&S '70, a popular student and natural leader who rarely sat still. "In the beginning, I felt that same isolation that everyone else described," said Tillery, Cincinnati's first elected black mayor. "But at the end of that first year, some friends and I started organizing the United Black Association, one of the first black student organizations to receive money from the university to operate.

Dwight Tillery was Cincinnati's first elected black mayor.

"We demanded formation of the African American Studies Department. We saw more black faculty arrive. Rev. (L. Venchael) Booth came -- the first black to serve on the Board of Trustees. The university let us use an empty building for a cultural center that we called the Black House.

"It was a very challenging time. It was the civil rights movement at its peak. We reflected what was going on in the country, and the 'News Record' wanted to cover everything we did.

"At that time, we dealt with a lot of systemic changes that institutionalized change in this university forever," he stated. "It was exciting to be here."

While the group did succeed in much, momentum diminished in the '70s and some promises were never honored. Providing a cultural center was one of them. "The university had made a commitment to us then, but there was a lack of follow-through," Tillery acknowledges.

The sense of alienation returned. "I am struck by the thought that the isolation was so strong that it drove us together," commented Roland West, Ed '73, who selected UC from among several schools offering him a basketball scholarship.

Roland West was the "top defensive man," from the 1966 "Cincinnatian."

"We had the feeling that we were nobodies. We listened to each other and took responsibility for each other. Our actions were driven by the attitude that we had better take care of each other because we were barely hanging on."

1980s and '90s

A few years later, the concept of uniting fellow blacks in the dorms took tangible shape when Alan Costner, BusAd '82, became founding president of the United Brothers of Dabney. The next year, he and the brothers started a similar group elsewhere, the Caucus to Improve Black Affairs of Calhoun Hall, where he was an adviser.

"I saw black brothers being kicked out of Calhoun that year," he explained, "and we decided to stop it. Basically, racist things were done against them, then when they would retaliate, they would get kicked out. We used the caucus to straighten things out."

As was too often the story, however, a few steps forward were followed by a giant step back. Costner's senior year was marred by one of the most embarrassing incidents in the UC's history.

"Campus was closed for Martin Luther King Day," he said, "and everybody was having their parties to celebrate. The SAEs (Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity) had a Martin Luther King 'trash party.' They came in every type of stereotypical dress concerning black folk. One person even showed up in a Martin Luther King mask with a bullet hole in it. We got them kicked off campus for five years."

In response, the African American student community rallied in greater numbers than ever. "At the beginning of the year, the United Black Association had 150 members," Costner said. "At the end, 2,000." But more important, the students took a stand for something positive, something that would outlast the anger and hurt of one intensely insulting incident: They approached the administration about the long-promised cultural center.

An early Tyehimba celebration, with African dance and other reminders of the African American heritage. Photo/Lisa Ventre

In '84, Joseph Steger took over as UC president and supported the idea. Finding a location took a while, but the Sander annex was remodeled and opened as the African American Cultural and Research Center in '91. Cecily Goode, BusAd '93, called the event "one of the most rewarding experiences I had while here."

She encouraged students in attendance to do more than simply enjoy the legacy left to them. "If you want something you never had, you have got to do something you have never done. When I entered campus in '88, anything you wanted to get involved in you could find. Much of it was a great influence on my life. There is a lot this university has to offer."

In all, stories ranged from tragic to triumphant, from frustrating to frivolous. Furthermore, memories were fresh for all alumni, even for the oldest living African American alumnus, 101-year-old Ida Rhodes, who joined the symposium by video.

Proudly displaying a special ring she wears to commemorate her UC degree from 1919, Rhodes remembered old classmates and instructors by name. "I was privileged to share with them," she said with a soft smile. "It was a delightful college of students. I so enjoyed that university."

Ida Rhodes, Class of 1919. Photo/Lisa Ventre

Georgia Beasley, 96, had accompanied the UC film crew to Rhodes' residence and dressed for the occasion -- in a skirted wool suit, tailored hat and pristine white gloves. Looking and sounding a good two or three decades younger than her 96 years, Beasley fondly thanked her sorority, the Sigma Omega chapter of Alpha Kappa Alpha, for guiding her through school.

"I knew I had to live through various segregated experiences," she said, "but I was never reluctant about anything. The sorority negotiated for me, and I was never afraid."

The University of Cincinnati's history has been dotted with African Americans who had courage and perseverance to take a stand and work for change. Eric Abercrumbie, UC director of Ethnic Programs and Services, wanted students to take ownership of that history and carry the alumni role models with them into the next century.

UC President Joseph Steger shared that vision. "One of the biggest burdens in the country today," he said, "is that we have no sense of history. We have to educate people about the past, because when you lack a sense of history, you don't care. And when you don't care, you do not take on responsibilities. Understanding the past gives you a purpose and a passion for today, as well as a determination for the future."

Cecily Goode agreed. "This is history," she said, looking around the center. "If we don't understand it and keep it, we will eventually lose it."

"Every time I walk in this building it's like a dream come true," said Harlan Jackson, BusAd '89. "I hear how it's filled up with students, and it warms my heart. This represents the opportunity for my children to come here one day and get a quality way to view our culture. This is an oasis."

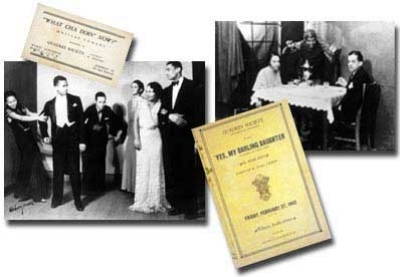

Photos/courtesy UC Archives and Rare Books Department

Quadres Society

To fight segregation at UC in the '30s, students like Donald Spencer (pictured acting in the left picture, second from left) founded Quadres, an organization that eventually allowed hundreds of black students to participate in activities from which they were traditionally excluded.

The Quadres Society put together successful plays, sponsored a writers group and even held dances to fund scholarships. Most minorities joined the group.

As the influence of Quadres spread across campus, soon other organizations, like the student newspaper, integrated.

Though it thrived for years, Quadres died quietly in the late '40s due in part to the growing popularity of black fraternities and sororities.

Past Issues

Past Issues