Dreams launch NASA careers

For decades, young people have dreamed about soaring into space -- after being tucked into bed with the story "Goodnight, Moon" or after watching "Buck Rogers" or "Star Trek" on TV. But when those aspirations begin to take shape with UC aerospace engineering degrees, then materialize with NASA careers, happily-ever-after endings are written. Here, we meet three alumni who say dreams do come true.

Scott Bleisath:

Designing space suits

With childhood dreams of becoming an astronaut, Scott Bleisath, Eng '88, found a career that is the next best thing -- helping to keep astronauts safe.

He spent his first 20 years at Mission Control in Houston, leading spacewalk operations for multiple space shuttle and International Space Station (ISS) missions. Today he is at the NASA Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio, working on the next-generation space suit.

Tomorrow's suit will involve more than just keeping astronauts secure. It's all about electronics and communication systems needed for computers, warnings, a navigation system that could be used to walk on an asteroid and a heads-up display to view information without looking down at instruments. A prototype suit is in the development stage, Bleisath says, and could be given a trial run on the ISS in a few years.

To test suits and help astronauts acclimate to working in them, Bleisath often works in simulators, either the 6.2-million-gallon water tank known as the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory or the "vomit comet," a fixed-wing aircraft that briefly provides a nearly weightless environment. He is also part of Desert RATS (Research at Technology Studies), a group of NASA professionals who test space suits and robots in extreme desert environments near Flagstaff, Ariz.

UC colleges with NASA alums Among them have been engineers, designers, lawyers, teachers and contract officers, with degrees from nine different colleges. |

"At Desert RATS, we are learning what is the correct type and amount of information needed by an EVA (extra-vehicular activity) crewmember," Bleisath wrote on his NASA blog. "Any electronics going on a space suit has to be very efficient from a size, weight and power perspective. So, we cannot afford to have any bells and whistles.

"Our team spent over a year talking to astronauts and other stakeholders to understand their needs. They made it clear to us that we cannot bog down the crew with too much information because that would hinder operations, rather than help."

Memorable experiences

First space shuttle mission to ISS -- Bleisath worked on STS-88, the first shuttle mission dedicated to the assembly of the space station. The shuttle carried the station's first American-made module, the Unity Node 1, and docked it to the Russian module already in orbit. Bleisath worked directly with Russian scientists on the two modules' interface and inspected the shuttle's payload bay at the Kennedy Space Center before launch.

Flight controller -- Bleisath also served as a flight controller, responsible for monitoring life-support systems. "You have to have immediate reactions to the unexpected," he says. "It's a very serious attitude."

Vital co-op assignment -- at NASA's Johnson Space Center.

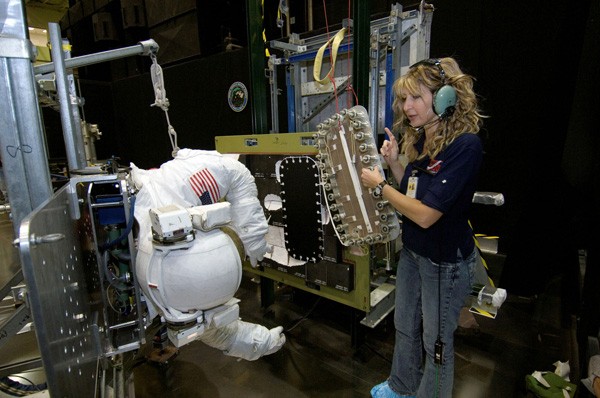

Scott Bleisath shares a prototype with colleagues at NASA.

Eric Haddox:

Exploring other planets

For Eric Haddox, Eng '00, the excitement of watching space shuttle launches at Kennedy Space Center (KSC) began during vacations in Florida as a child.

Today, he has a career at KSC as flight-design lead engineer in the Launch Services Program, which launched the 4-ton Juno spacecraft in August 2011 for a five-year trip to Jupiter, where it will gather data about the planet's origins, structure and atmosphere.

"We launch all of NASA's science missions," he says. "We manage and contribute to the design of the launch vehicle trajectories, which put all of those spacecraft into their orbits. My job is to lead the trajectory design group."

Haddox's career has made an interesting cycle from his co-op job at Lockheed Martin where he worked on space shuttle reentry systems. Such systems involve flight-simulation software to train astronauts for reentry in real-time scenarios, including failure or abort situations.

Complicating his task was the fact that the shuttles fell from orbit totally unpowered and had only one shot at making the landing site, Haddox explains. Engineers had to calculate the amount of energy the vehicle had in order for it to make it to KSC the first time. If a shuttle came down too fast, it burned off too much energy to reach the landing facility; if it came in too slowly, it risked overflying the site.

Currently, Haddox is concerned with a vehicle being at a certain point in space at a given time. Beyond determining the precise time to launch, the team analyzes the vehicle's load requirements, its power, telemetry, thermal and acoustic considerations, as well as payloads. "Weight is precious," Haddox says. "You want small batteries, for instance, in order to maximize the science on the vehicle."

Haddox says that NASA currently has 30 to 35 missions being worked in various stages and that he is working on many different missions for commercial launch vehicles. "NASA is using this program as a model for the new commercial space program for astronauts."

Memorable experiences

Science missions -- Haddox worked on the two Mars rovers; the Messenger program, which put the first spacecraft in orbit around Mercury in March; the New Horizons spacecraft, which was dispatched to Pluto in 2006 and is due to arrive there in 2015; and the GRAIL mission (Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory), launched in September to measure the moon's gravity and determine its interior structure.

Next up -- the November launch of the Mars Science Laboratory with a rover named Curiosity to look for evidence of microbial life.

Vital co-op assignment -- at Lockheed Martin, working directly with astronauts, especially John Young.

Lora Atkins Bailey:

Dealing with spacewalks

If childhood dreams can be responsible for cultivating NASA careers, then Lora Bailey, Eng '88, has her grandfather to thank. She recalls him saving news clippings on every conceivable topic about space, but she most poignantly remembers standing with him in his yard, looking at constellations and shooting stars. He died when she was 10, so he never realized how his passion cultivated her career.

As a structural-loads expert for EVAs (i.e., spacewalks), Bailey helped determine how crew members could service the Hubble Space Telescope and how members of another mission could repair a shuttle's thermal-protection tiles while in space. Technically, she performs load predictions for crew members working on external payloads outside a shuttle.

The telescope, for instance, was an external payload. "Hubble is captured and placed in the payload bay," she says. "Then the crew would climb on the telescope with those delicate instruments inside." What impact did they have on the intricate circuitry inside? That's what Bailey had to calculate.

Her most notable assignment followed the 2003 loss of the Columbia shuttle during its re-entry into the Earth's atmosphere. In response, she helped create a tile repair method and helped design and test a 50-foot extension to the shuttle's robot arm, which enabled astronauts to reach the full underside of the shuttle to make repairs.

One concern was that such a long, cantilevered boom would be too flexible and "crew-induced motion would preclude being able to do any real work because the boom system would sway around too significantly," Bailey explains. "My tests showed that a crewmember could indeed conduct operations on the end of the boom despite the fact that it was extremely soft and could sway readily.

"This design and test effort was truly a crowning achievement for me personally," she says. "It used every engineering brain cell that I had to produce it."

As the space shuttle program grew to a close, Bailey noted, "People are still celebrating the end of the program with pride for our accomplishments, but it is a sad day here at the space center. A real and present part of us is gone.

"But we are too young to not vigorously seek out and create our next bold venture, as well as the fleet of vehicles that will bring it to fruition. Keep your eye on us. We're not done yet."

Memorable experiences

Imax movie realities -- For an Imax movie to be shot in space, Bailey's division made sure the camera could operate in space and determined how to keep the camera safe, particularly during the launch's severe vibrations, which could wreak havoc on electrical circuitry.

Next up -- Bailey has been working on the primary structure and landing gear for a new lunar lander.

Vital co-op assignment -- at McDonnell Douglas, working directly on software programming and mainframe computer problems related to the shuttle program.

Related articles:

UC alum John McCullough helps complete final shuttle mission

What's next for NASA?

Past Issues

Past Issues