by Mary Niehaus

"Medicines matched to an individual's genes? By 2005? That is just too soon. No one will believe it." The journal editor was prodding the University of Cincinnati researcher to push the date to at least 2010. But Stephen Liggett was not budging, insisting his prediction about personalized medications was valid.

When the national publication came out, however, Liggett's article clearly read 2010.

Did the editors of Nature Medicine have an explanation? "They said they forgot," says the chief of pulmonary and critical care medicine and professor of medicine and pharmacology at the College of Medicine.

"I know that 2005 is only four years from now, but it seems to me we've underestimated the pace of the progress of the human genome," he contends. "At one time, we said it wouldn't be finished for several more years, and it's already complete."

Liggett's pioneering attitude is typical of UC's approach to genetic discovery and basic science.

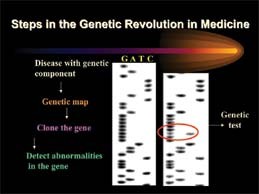

"Genome" is scientific shorthand for the full set of genes an organism carries in each cell. Early in the search, scientists were able to identify individual human genes only after long hours of painstaking laboratory studies of microscopic strands of DNA.

As the race heated up, computerized robotics were used to check thousands of DNA samples per second, 24 hours a day. By June of 2000, scientists from the publicly funded U.S. Human Genome Project and a private company, Celera Genomics, jointly announced that they had successfully mapped and sequenced the 30,000 genes of the human genetic code.

Today, David Millhorn, [above] chairman of molecular and cellular physiology at the College of Medicine and director of the new University of Cincinnati Genome Research Institute (UC opens new genome research institute) says "tons" of genomic data are now available for study in this "post-genome" era. "The challenge," he confirms, "is to take this information and apply it to understanding complex biological problems and disease processes that are regulated by the simultaneous expression (turning on) of numerous genes."

Most of us think of genes as those invisible bearers of qualities we inherited from our parents and grandparents: brown eyes like Grandma's, a freckled nose like Mom's or athletic ability like Dad's. Genes are the things we praise or blame when we identify characteristics that "run in the family," such as twins, longevity or allergies.

Past Issues

Past Issues