Latest Magazine

September 2018

September 2018

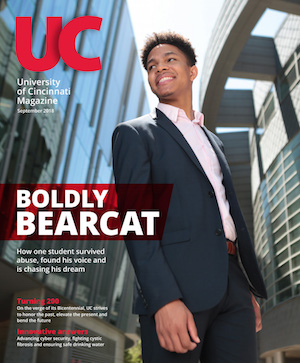

Boldly Bearcat

Finding his voice

Danger in the tap

Virtual defense

Global game changer

Celebrating UC's Bicentennial

Past Issues

Past Issues

Browse our archive of UC Magazine past issues.

What We Do

Our staff of professionals serves as communications consultants, promoting the university and serving as a liaison between the news media and the university community. We are the officially designated office for the university to communicate to the public at large through the mass media.

Media Contacts

Public Records Policy

Inspiration accelerated

Hyperloop UC grew from a single student with an idea to a campus movement

by John Bach

Photos by Jay Yocis

Dhaval Shiyani was working the graveyard shift at a University of Cincinnati residence hall in 2015 when he stumbled upon Elon Musk's original Hyperloop white paper online. By the end of the night, he had fallen in love with the billionaire inventor’s concept, a tube-based passenger system that would rocket pods of people between cities at the speed of sound.

The aerospace graduate student knew he had to get involved.

Over the next 18 months Shiyani, assembled dozens of fellow students who this week have advanced to the finals of a worldwide competition sponsored by SpaceX to build the best Hyperloop pod prototype.

“It is sort of like an engineering olympics,” says Shiyani. “We are competing against the rest of the world. But that is good. This kind of competition encourages innovation and fast-paced technology advances.”

Hyperloop UC team leader Dhaval Shiyani inspects the details of their space frame in the final week before shipping it to California. photos/Jay Yocis

On Sunday, Jan. 29, they’ll get to see how their creation performs in a pod vs. pod throw down with 28 other teams from across the US and as far away as Japan, Australia and the Netherlands. It’s a select group of teams that have made the trip to Hawthorne, California, where SpaceX is headquartered, especially considering the contest started with more than 1,200 conceptual entries. Of those, 120 advanced to design weekend in Texas last year, and just 30 (one dropped out) were invited to build prototypes.

In the final test, pods will be loaded into a mile-long, 6-foot diameter de-pressurized steel Hypertube, then fired forward by a “pusher” as teams wait to see if their design holds up under stress and stops before the end of the track. Those that don’t brake in time will barrel into a foam catch pit at the end. Hence the SpaceX hashtag #breakapod.

The Hyperloop test track stretches for a mile adjacent to the SpaceX headquarters in Hawthorne, California. photo/Courtesy of Teslarati

Shiyani compares the Hyperloop competition to the space race of the 1960s.

“This shows that if a society and a people are determined to do something, you can do things like land on the moon,” says Shiyani, whose team had worked around the clock for weeks to finalize their entry. A week prior to the contest, he admitted to getting only about eight hours of sleep in the previous three nights total.

“I could lay down and sleep on this floor,” he said then, pointing to the concrete inside the High Bay of Rhodes Hall at UC where they did assembly and testing. “Since it is toward the finish line, there is a lot of panic.”

He and 29 other students representing Hyperloop UC are now in Hawthorne, California with hopes they can contribute to the technology they believe will ultimately shift high-speed transportation as we know it, an advance that would allow travel and shipping at roughly 200 mph faster than commercial airliners. The impact would effectively close the commuter gap and allow passengers to live 400 miles from work and still commute in under 40 minutes. Think Cincinnati to New York in under an hour, or Los Angeles to San Francisco in 30 minutes.

Sid Thatham heads business operations for Hyperloop UC and has largely been the face of the team on campus.

In addition to the SpaceX contest, private firms unassociated with SpaceX are also carrying Musk’s idea forward by building Hyperloop infrastructure in the United Arab Emirates, South Korea, the Czech Republic and other locations around the globe.

Ironically, as Hyperloop comes to fruition, society may have LA traffic to thank for the inspiration. Fed up with the daily snarl, Musk, CEO of both Tesla and SpaceX, thought up the idea while sitting in gridlock. He first cast the vision in 2013 when SpaceX posted his 58-page PDF, complete with back-of-the-napkin type calculations. The big idea was to connect major cities with elevated vacuum tubes that would allow passenger pods to dart along on a cushion of air at more than 700 mph.

The concept sounds outrageous. Picture a bank tube on a grand scale. It would be both faster and more sustainable than either air travel or high-speed rail, yet, according to Musk, it is absolutely achievable.

The visionary challenged the world. He would build a tube to test concepts, but he was counting on others to supply the pod technology. Musk laid down the gauntlet in the form of an open-source competition where teams would assemble a team, develop ideas and go to work on design concepts.

Members of Hyperloop UC include Sudeshna Mohanty (far left) and Rohan Deep Chawla (second from left). Operating the drill is Abhishek Soni. photos/Jay Yocis

"I'm pretty excited," shares Sudeshna Mohanty, who is persuing her master's degree in mechanical engineering at UC. "Seeing our pod on the track is going to be an excellent feeling. I'm just glad that I had a chance to come to UC and be a part of this team and see this. This is something that has not been done before, a new technology, and you don't get a chance to work on something like that everyday."

She is part of Hyperloop UC's structures team, as is Rohan Deep Chawla. Both are from India, as are most of UC's crew.

"It is like we are part of a dream," say Chawla. "It is Elon Musk's dream, but we all feel like we are participating in it. And if we can contribute to it, it will be great. We feel like we are building something for the future."

Vignesh Jayakumar is pursuing his PhD at UC in mechanical engineering. He leads the structures and vibrations team for Hyperloop UC.

Business and engineering graduate student Sid Thatham with Hyperloop team advisor Shaaban Abdallah.