Farewell Neil Armstrong: UC’s most famous, humble professor

Little-known insights tell how one small step led to a reluctant hero

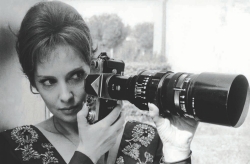

Although most UC engineering students in 1974 knew the name Gina Lollobrigida, none of them would have recognized the Italian actress on the street, much less in Baldwin Hall. But around 5 p.m. on March 25, students, who were getting a bit bleary eyed at the end of the day, snapped to when a stunning woman glided through the doorway, armed with camera gear and asking to take photos of their professor, Neil Armstrong.

“We didn’t know who she was, but she sure looked special,” recalls Ralph Spitzen, Eng ’74, MBA ’76. “We looked at Neil’s face, and he gave no indication of anything. We looked back at her, and she was still looking special.

“As we looked back and forth, Neil still had a blank face. Finally, he said, ‘Gentlemen, this is Gina Lollobrigida.’ We did recognize her name.”

It turned out that Armstrong had joined a large party at Gina’s home in Italy while he was on a worldwide first-man-on-the-moon tour. Five years later, she was a Ladies’ Home Journal photographer who wanted a photo shoot with Armstrong.

For Spitzen’s classmates, those memories remain vivid today, months after Armstrong’s Aug. 25, 2012, death. But most people never realized Armstrong, HonDoc ’82, was a UC aeronautical engineering professor for almost a decade, from 1971-79. In fact, there is much the public doesn’t know about UC’s most famous professor.

This foggy awareness came from Armstrong’s strong disdain for media hounding him and his yearning to be treated like “Mr. Average Guy,” wrote Al Kuettner, UC director of information at the time.

“Neil viewed himself as just an ordinary person,” adds engineering professor emeritus Ron Huston, who worked closely with him. “He fully understood that the moon landing was the result of long, hard work of many people. Neil did not want to leave the impression that he did it all on his own.”

“We didn’t bug him and treat him like a star,” says Awatef Hamed, current head of UC’s School of Aerospace Systems and a 1970s faculty member. “We just went to lunch with him and talked in the hallways. He went to his office and did his work like the rest of us.”

Most faculty and students respectfully avoided mentioning his past accomplishments, but student outliers would climb on each other’s shoulders to peer into his Rhodes Hall office window, colleague Huston recalls. In addition, autograph seekers were relentless in public. To ward off such interlopers, UC kept his name off his office door and out of the directory.

“He is constantly badgered,” director Kuettner noted in 1976, “to sponsor commercial products, to make speeches and to write articles.” Reporters were the worst, he said, “staking out” his Warren County farm and “slipping” into his classroom.

“Because of his determination to be a private citizen,” Kuettner wrote, “Armstrong is often labeled a recluse and a ‘funny guy.’ Actually, neither reference is accurate. Those who know him best recognize that he really does desire to be out of the limelight and that he is a very bright scientist in serious pursuit of scientific knowledge and research.”

In a statement released after his death, his family called him “a reluctant American hero who always believed he was just doing his job.”

When Armstrong died at age 82 from complications related to cardiovascular procedures, we realized what little attention had been paid to him during his UC tenure. So we dug through dusty files to find some intriguing hero highlights, which we list below.

Armstrong’s firsts

- NASA’s first civilian astronaut

- Among the first test pilots to fly the X-15 rocket-powered aircraft, 1963

- Accomplished the first docking of two spacecrafts as command pilot of Gemini 8, 1966

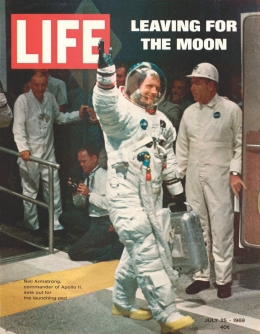

- First man to walk on the moon July 1969

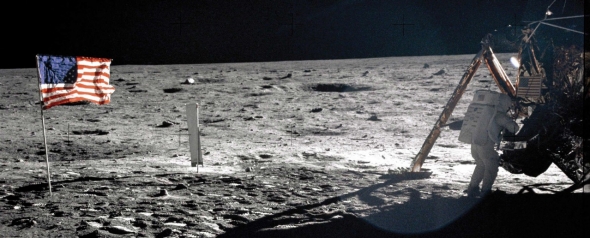

Moon rocks

On July 20, 1969, Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin spent two and a half hours on the moon’s Sea of Tranquility, conducting experiments, taking photographs and collecting 47 pounds of moon rocks and dust, all of which had to be declared at a U.S. customs office in Hawaii before they could enter the country. (John Mays, JD ’66, gave us a copy of the original document, which his friend Neil Armstrong had given to him.)

Each sample had to be itemized, and the form asked, “Are you bringing with you: plants, food, animals, soil, disease agents, cell cultures or snails?”

Most answers were brief. In the form’s space for “flight number,” “Apollo 11” was typed. The “departure point” read “Moon,” and the “arrival location,” “Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S.A.” The Declaration of Health section asked travelers to list: “Any other condition on board which may lead to the spread of disease.”

The answer: “To be determined.”

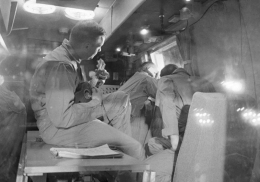

President Nixon visits Armstrong and his crew while they were in quarantine. Photo/courtesy of NASA.

Under quarantine

After splashdown, Apollo astronauts lived in quarantine for 21 days to be sure hitchhiking lunar microbes would not harm the Earth. First, the Apollo 11 crew left their space capsule wearing biological isolation suits, then boarded a recovery pickup helicopter to reach the U.S.S. Hornet aircraft carrier.

After landing on the ship, the copter was towed onto an elevator and moved next to the Mobile Quarantine Facility, which was virtually a sealed Airstream trailer. The astronauts, still bagged and sealed themselves, walked briskly for 30 feet to enter the trailer, where they could finally wave at their wives, as well as President Richard Nixon, from behind glass. When the ship reached Hawaii, the trailer and men inside were flown to Houston, where the crew moved into a glass-enclosed laboratory at the Manned Spacecraft Center.

Degrees of fame

The astronauts:

- Met Queen Elizabeth, Pope Paul VI and Japanese Emperor Hirohito.

- Were welcomed home with giant ticker-tape parades in New York City, Chicago and Los Angeles — all in one day and concluding with a state dinner where President Richard Nixon presented them with the Medal of Freedom.

- Toured on Air Force One, along with their wives, appearing in 28 cities and 25 countries in 35 days to greet millions of people. The trip ended with an overnight stay in the White House.

Humble heart

“I am, and ever will be, a white-socks, pocket-protector, nerdy engineer. And I take substantial pride in the accomplishments of my profession. Science is about what is; engineering is about what can be.”

— Neil Armstrong, February 2000, at National Press Club event including him among the 20th Century’s Top 20 Engineering Achievements.

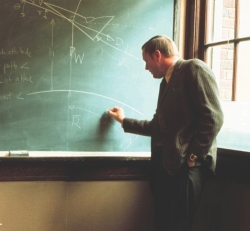

Ready to teach

“I’d done a little teaching before, and I had always said that one day I’d go back to the university. There were a lot of opportunities, but the University of Cincinnati invited me to go there as a faculty member and pretty much gave me carte blanche to do what I wanted to do.”

— Armstrong in the NASA Johnson Space Center Oral History Project, 2001

Anything for students

“For his students, he couldn’t have been any more approachable. He was always willing to sit down with you and answer any questions. He was a great aviator who enjoyed having beers with students after final exams.”

— Ralph Spitzen, Eng ’74, MBA ’76

Love of teaching

“I love to teach. I love the kids — only they were smarter than I was, which made it a challenge.” — Armstrong, 2001 Oral History Project

“He didn’t want accolades; he only wanted to teach. He really worked hard at just being a teacher. He was a true servant of his profession.”

— Ed Bridgeman, A&S ’83, UC police chief while Armstrong was on campus

Souvenir in his office

A prescription bottle of motion-sickness pills, presented by a Soviet cosmonaut with best wishes for a safe journey to the moon and back home — “a most interesting gesture considering the state of the space race between the Soviet Union and the United States at the time.”

— former student Ralph Spitzen

Shielding Armstrong

“I erected buffers to shield Neil so he could get his work done. A lot of people just wanted to touch him.”

— UC Police chief Bridgeman

“I have spent a good deal of my time at UC trying to ensure that exploiters and nuts — in the press and elsewhere — do not harass you.”

— director of information Al Kuettner to Armstrong, 1976

Why he left UC

“I stayed in that job longer than any job I’d ever had up to that point, but I decided it was time for me to go on and try some other things.”

— Armstrong upon his Jan. 1, 1980, resignation, Oral History Project, 2001

Having the ‘right stuff’

"What we saw was a man with an extraordinary ability to adapt and to learn with incredible speed. Couple that with a sixth sense when it came to timing in the face of escalating risks, and you have the right stuff to be Apollo 11’s commander.

“The man who walked on the moon also liked keeping his feet on the earth and his eyes to the sky. And that’s the Neil Armstrong my classmates and I knew.”

— former student Ralph Spitzen

Honors

A fellow of the Royal Aeronautical Society, decorated by 17 countries, recipient of the Royal Geographic Society’s Gold Medal, the Federation Aeronautique Internationale’s Gold Space Medal, the first U.S. Congressional Space Medal of Honor (from President Jimmy Carter), the U.S. Congressional Gold Medal (from President Barack Obama) and the NASA Distinguished Service Medal.

“As long as there are history books, Neil Armstrong will be included in them, remembered for taking humankind’s first small step on a world beyond our own,” stated NASA administrator and former astronaut Charles Bolden upon Armstrong’s death. “As we enter this next era of space exploration, we do so standing on the shoulders of Neil Armstrong.”

Latest UC-Armstrong links

- Armstrong’s estate donated memorabilia to UC Archives last fall.

- UC aerospace director Awatef Hamed, who worked with Armstrong in the ’70s, recently helped create the “Professor Neil Armstrong Memorial Scholarship Fund” along with two of his former students, Tom Black, Eng ’77, and Ralph Spitzen, Eng ’74, MBA ’76.

- The BBC thanked UC Magazine in the credits of the “Neil Armstrong: First Man on the Moon” documentary, which aired five times in the United Kingdom. Alumnus Ralph Spitzen was featured in the film.

- UC Magazine received credit for Armstrong’s two-page obituary published in the Royal Aeronautical Society’s international Aerospace Professional magazine.

- Customs declaration for moon rocks — View document signed by all three Apollo 11 astronauts to bring moon samples into country.

- Wrecks and near wrecks — Armstrong's fiery close calls in the air and mishaps on campus.

- Memories of goose bumps, getting thrown out of class — UC faculty and alumni talk about the Armstrong they knew.

- Armstrong's private life — Thoughts from someone who worked closely with him at UC.

- Armstrong's poem for children — About where he went on his summer vacation — to the moon.

- UC Commencement address — Armstrong's insightful 1982 address.

- Paper airplanes — See professor Armstrong making paper airplanes with students.

- UC Magazine's Web-exclusive feature — Photo gallery and detailed article on Armstrong.

LISTEN (courtesy of NASA)

- Audio fiile of the Apollo 11 liftoff

- Other audio files of Apollo 11 crew on the moon

VIDEOS

- WCPO news segment filmed at UC in memory of Armstrong.

- NASA restored videos of Apollo 11 on the moon

- President Barack Obama honoring the astronauts

LINKS

- Armstrong Remembered page created by the College of Engineering and Applied Science

- Armstrong's family website

- New York Times story

- Armstrong Air & Space Museum in Wapakoneta, Ohio

Past Issues

Past Issues