By Rachel Richardson

Photography by Joseph Fuqua II

UC’s new high school ambassador program could serve as a national model for helping low-income and first-generation students attend college.

I

t’s morning and Nya Williams strides confidently into a classroom of a dozen 12th-grade students chattering animatedly about the hotly contested campaign for homecoming queen and king. An eager young woman with a ready smile and a head full of bouncy curls, Williams deftly brings the class at Cincinnati’s Withrow University High School to attention and asks about their college plans.

A hand tentatively goes up. “I want to go to the University of Cincinnati, but my GPA’s not so good,” admits a rangy student slouched low in his chair. “Can I even go to college?”

“That’s a good question,” replies Williams. “You can go to UC Blue Ash and work on your GPA there, get that up and transfer to main campus.”

Next, Williams heads to her desk in the school counselor’s office, where she guides as many as 15 anxious students a day in navigating what seems to many a complicated and overwhelming maze of college admission and financial aid applications.

But Williams isn’t a school guidance counselor or college advisor.

She’s a student herself, a graduating senior and a member of the Cincinnati Public Schools High School Ambassador program, a new initiative launched by UC in collaboration with CPS to increase the number of students who enroll in a postsecondary institution.

The venture, believed by organizers to be the first of its kind in the nation, holds the promise not only of boosting the socio-economic futures of students in Ohio’s third-largest school district, but could serve as a model to propel underserved students nationwide, particularly low-income and first-generation students, to attend college.

“This is really first of its kind where you have peers facilitating programming throughout the year for their peers,” says De’Recco Lynch, UC’s associate director of admissions, who helped develop the program. “We’ve not seen anything like this before.”

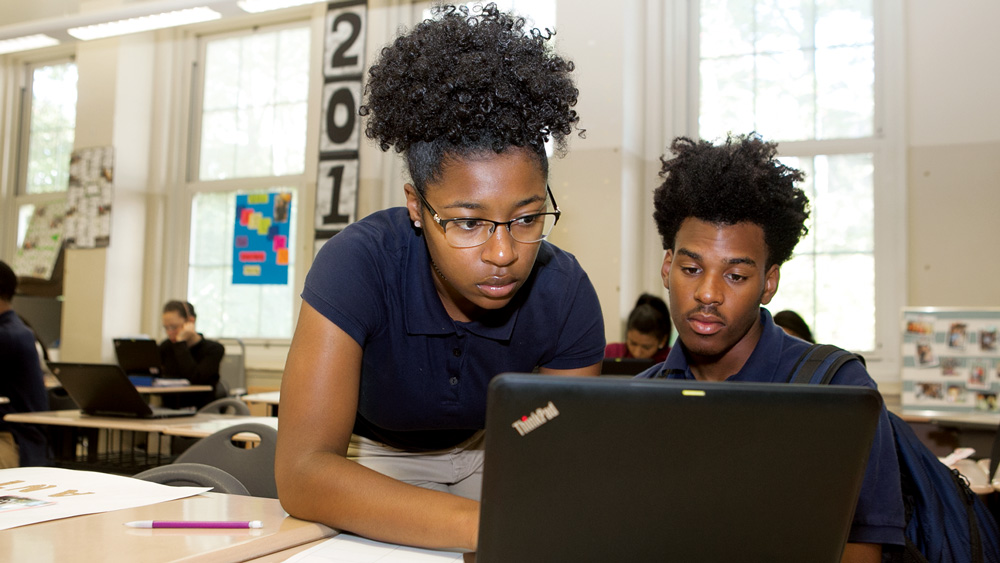

Nya Williams, a senior at Withrow University High School and a Cincinnati Public School Ambassador, directs a fellow student to an online scholarship resource. The aspiring broadcast journalist says peer programs like CPS Ambassadors can sometimes reach students in ways adults can’t.

Students become teachers

CPS Ambassadors employs a team of high-achieving students — two seniors from each of CPS’s 14 high schools — to serve throughout the school year as peer resources in the college search and selection process. Students are compensated $10 an hour for all UC-supervised activities, and those who decide to attend UC receive a $2,000 financial grant.

Ambassadors undergo an application process that requires two letters of recommendation, an essay and an interview with UC staff. Those selected then attend more than 40 hours of training. The 11-week summer course, which includes field trips, campus tours and a community service project, introduces them to a wide range of topics on college access while also helping them hone important time management, leadership and networking skills.

The comprehensive program is eye-opening even for students who have a parent or other adult in their lives who applied for and attended college.

“I thought I already knew about college, but I didn’t know all this,” admits Iona Cottrell, a senior at Woodward High School. “Like, I didn’t really care about college deadlines. I thought you could just apply, but learned you have to apply by a certain deadline.”

“I already had some background on the college application process and financial aid,” echoes Amyas Dawson, who attends Clark Montessori, “but I really got an opportunity to learn about scholarships I didn’t know about and programs like the Gen-1 program at UC.”

Throughout the school year, ambassadors offer monthly programs based on the needs of their classmates. UC staff are on hand to guide and supervise the events, but the students plan and lead the activities.

“We have 14 high schools that each have a different makeup,” explains Carver Ealy, UC’s assistant director of multicultural recruitment. “Some schools might need the very basics of financial aid. Other schools might just need help filling out the FAFSA.”

The role reversal of students becoming the teachers might make for an unusual approach, but it’s one grounded in established research on teen social behavior. If peer pressure can lead youngsters to engage in risky behaviors, why not leverage that powerful sphere of social influence to improve educational outcomes?

“Rather than [us] selling the university and the things that we do, we hope that the ambassadors … will really make the case to their peers in a way that we can’t reach them,” explains Ealy. “We hope that they choose UC as their home, but more than anything, we want to make sure that they end up in college.”

Just weeks into the school year, Williams, an actress who plans to pursue a career in broadcast journalism, has already seen success in her innovative peer outreach attempts. The enterprising senior class president uses her role as the “Voice of Withrow” in morning announcements to spotlight students who’ve been accepted to their colleges of choice. Now throngs of college-bound seniors clamor for their minute of academic fame among the school’s 1,275 students.

Williams and fellow Withrow ambassador Te’A Freeman also respond to questions posted on a private Facebook group for the school’s class of 2018 and notes left in a “Curious Tiger Box”— a reference to the school’s mascot.

“We’re actually going through the same process as them,” explains Freeman. “You may feel like the adult doesn’t understand, but coming from someone who’s in the same position is easier to listen to.”

“When it comes to adults, it feels more like nagging,” adds Williams. “If it’s a peer, you actually have a conversation. A lot of people don’t have that push to attend college at home. If you get that motivation at school, especially by a peer, I think they will listen.”

AIMING HIGH

For students who are first-generation or low-income, that kind of social push to pursue college can have life-altering consequences. College is a powerful engine for upward economic mobility, organizers say, and a postsecondary degree can mean the difference between a lifetime of poverty and a secure economic future.

At Withrow, which the school’s state report card designates as having a “high” poverty rate, resources are stretched, says guidance counselor Tracey Williams, a UC alumna whose caseload includes 652 students, 200 of whom are seniors.

“I don’t have time to sit with 200 students and step-by-step walk them through the Common App,” she said, referring to the admissions application used by nearly 700 colleges and universities in the U.S. and abroad. “If I don’t have somebody to help me, somebody might get dropped because I just can’t do it all.”

Student Williams not only guides others in filling out the application, but, as counselor Williams points out with a laugh, “She’s gotten them to do more Common Apps than I had last year by myself.”

“You may feel like the adult doesn’t understand, but coming from someone who’s in the same position is easier to listen to.”

—Te'A Freeman

Withrow guidance counselor Tracey Williams says CPS Ambassadors Nya Williams, back left, and Te’A Freeman, right, are instrumental in helping ensure that none of the school’s seniors slip through the cracks.

Back in the Withrow guidance counselor’s office, Freeman shrugs off her bulky backpack and grabs another question scribbled on notepad paper from the Curious Tiger Box.

The CPS Ambassador program, she says, not only steered her to become the first in her family to attend college, but also motivated the aspiring physical therapist to aim high.

“It’s opened my eyes to college and college life,” she says. “I didn’t have anyone to tell me about FAFSA or that there are scholarships I can apply for. Now I can tell other people what I know so that they don’t struggle.”

“I want to go for my master’s, possibly my doctorate,” she adds matter-of-factly. And then, with a smile, “Dr. Freeman — now that sounds good!”

LINKS:

Rachel is a public information officer with the University of Cincinnati and a contributor to UC Magazine. As a former multimedia journalist and two-time alumna of UC's McMicken College of Arts & Sciences, Rachel is thrilled to have the opportunity to share the stories of UC's amazing community of faculty, staff, alumni and students.

Additional Credits: Thanks to photographer Joseph Fuqua II, designer Margaret Weiner as well as web developers Kerry Overstake and Carolyn Noe for helping to develop and present the content contained in this piece.

FEATURES

Inspired by her mother, DAAP alumna launches clothing line for women recovering from breast surgery.

The 1991 implosion of UC’s Sander Hall continues to reverberate with the upcoming release of a powerful new book about the building’s architect from the perspective of his daughter.

Matt Berninger and Scott Devendorf of alt-rock band The National reflect on their formative years at UC.

UC’s new high school ambassador program could serve as a national model for helping low-income and first-generation students attend college.

How a local man gained precious time with his family thanks to innovative UC cancer treatment.

Leading urban public universities into a new era of innovation and impact.