The 1991 implosion of UC’s Sander Hall continues to reverberate with the upcoming release of a powerful new book about the building’s architect from the perspective of his

daughter.

Few things seem to unite UC grads like the lore of Sander Hall. Every time UC Magazine writes about the high-rise dormitory, alumni share stories of either living there in the ’70s and early ’80s or watching the 27-story behemoth fall in 1991. Just when we thought we had sufficiently documented the building — from the countless memories of student antics inside, to the tales of the implosion — along comes a book with a perspective no one else could have.

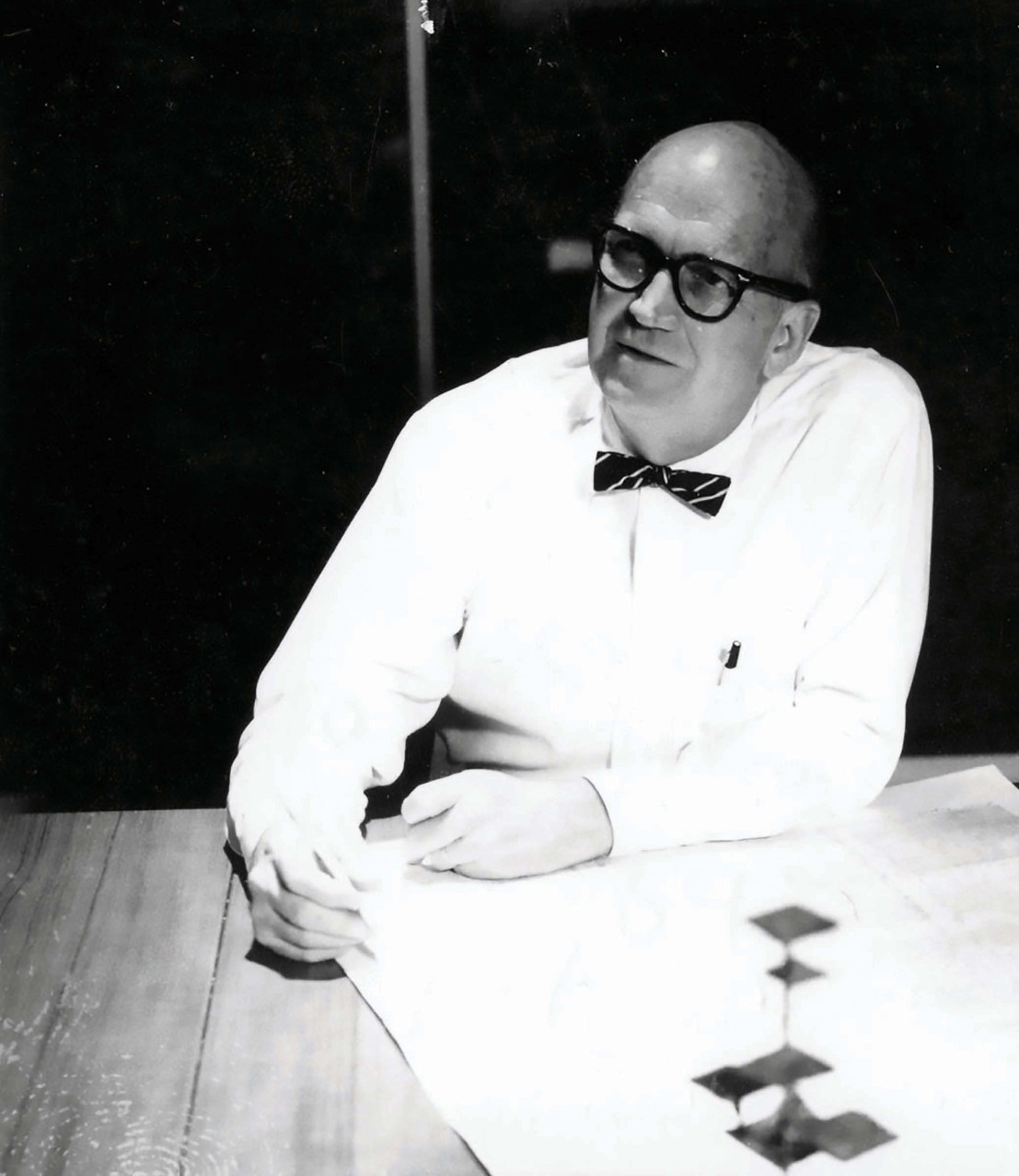

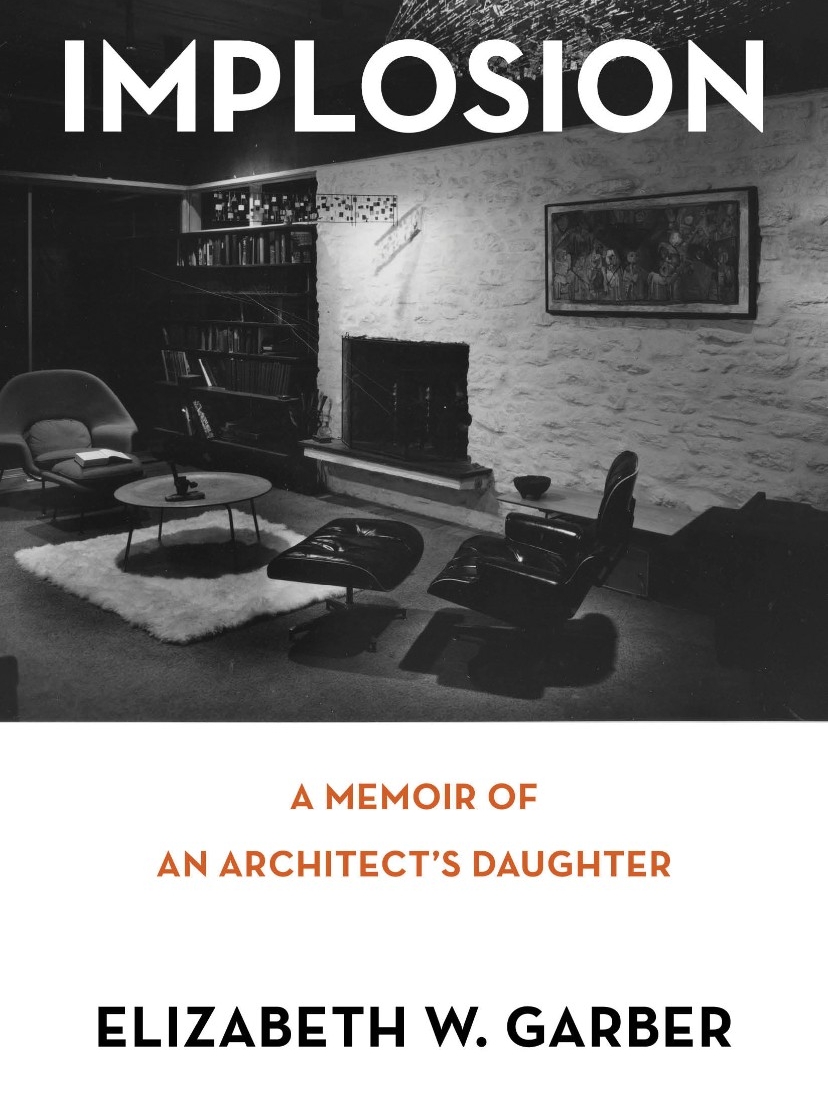

“Implosion: A Memoir of an Architect’s Daughter” hits the shelves in June 2018, and in it author Elizabeth Garber unfurls a deeply personal sketch of her father, modernist-architect Woodie Garber, who designed not only Sander Hall but also UC’s College of Nursing. Daughter Garber, a published poet, writes with a certain sensitivity and eloquence while giving readers a long look into the radically modern all-glass home she and her siblings helped build in Glendale, Ohio, in the mid-’60s.

Reviewer Patrick Snadon, emeritus professor of architecture and interior design from UC’s College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning, says Garber takes readers “behind the scenes to show what sacrifices were made by women and families in the creation of modernist buildings.” He goes on to say that in analyzing her family’s life, she details her father’s “chaotic, self-centered and rather mad personal life … where moments of tyranny and abuse creep upon us with a shock.”

Excerpted from

“Implosion: Memoir of an Architect’s Daughter”

By Elizabeth Garber

n a June morning in 1991, three years before my father died, I was working in the garden with my children playing nearby. I had no idea my father was standing on a houseboat anchored at a precise location in the earth-brown Ohio River. He mentioned it casually over the phone a week later, as I spooned oatmeal for my one-year-old daughter. He said, “We met early at the dock.” Bob, the mechanical engineer for Sander Hall, had helped my father aboard, before motoring downstream until he angled his boat into position, out of the current. Tugs rumbled by, maneuvering barges piled with small mountains of glistening coal.

My father, nearly 80, his back curved over from osteoporosis, had brought a bottle of chilled champagne. They trained their binoculars on the top floors of the mirror glass dorm that appeared, like a Japanese kite, flying high above the tree-covered hillside. They checked their watches and looked up every few seconds.

From that distance the tower had appeared as beautiful as my father had envisioned it, silvery rose mirrored walls rising high above the earthly world, where clouds floated over the surface, like the painting I’d seen in his office, a building surrounded with grass and trees. But my father’s grand vision had been hijacked by a miasma of circumstances. The tower was inextricably knotted into a collision of 1970s radical social change, wealth and poverty, racial inequality and battles between administration and students in a roaring fury against the establishment that Sander Hall represented.

Modernist architect Woodie Garber designed UC’s infamous Sander Hall, the gleaming high-rise dormitory he hoped would crown his career. Instead, it was dynamited into rubble.

After I left home I’d heard occasional reports on Sander Hall. It was known for an epidemic of arson. Smoke rising up stairwells. Smoke seeping into dorm rooms. Eleven years after it was opened, a panicked girl used her desk chair to smash through the mirror glass wall of her sixth-floor room to escape the smoke. Firemen on a ladder lifted her down. The university closed the building.

Studies battled over the fire safety of the dorm. Did it meet state code? What could be done to increase the safety of the building? Add an additional stairwell at the end of the building? Newspaper articles debating the issues stacked up on my aging father’s desk. An occasional letter to the editor praised the building and declared it was the students who had been the problem. The university considered changing the tower over to administrative offices. But the price tag for renovation came back nearly the same as for a new building.

The university finally abandoned the building, leaving it to stand empty, a dark derelict tower, a shadow hanging over the university for nine years. Twenty years after the hall opened, in 1991, the president of the university was quoted in the Cincinnati Enquirer, “If I didn’t know better, I’d say the building was haunted.”

Throughout my childhood my father always declared, “I’ll be an architect until the day I die. It’s in my blood.” Yet no one could have guessed in the weeks before the ribbon-cutting ceremony for Sander Hall that the financial recession of the 1970s would halt major construction in the U.S. for years. In 1971, Sander Hall looked like the pinnacle of Woodie’s success, with the promise of more work to come. He held onto his empty office for a few years, finding consulting work, and finally, he taught a few classes to architectural students at Miami University.

On campus [in 1991] the crowds started gathering hours before, some had stayed up all night partying and waiting. They pushed up close to the police barricades. Mid-June, Saturday morning, the University of Cincinnati campus should have been sleepy and quiet on summer school schedule. But surrounding the campus on flat roofs of cheap apartments, students clasped mugs of coffee and munched on bagels. Figures lined the top floors of university buildings. Crowds lined Calhoun in front of bookstores, head shops and the falafel shop where they would put up a framed series of second-by-second photographs of that day. Everyone waited, their eyes tracing the familiar high-rise dorm, Sander Hall, which had stood on the east side of campus since the turbulent early 1970s.

Twenty-seven stories tall, a grid of strong vertical lines with horizontal mirrored panels from an era famed for glass buildings, the dorm reflected two church steeples, pearly clouds and plumes of airplanes across its glistening surface. On either side of the building, the column of windows was edged with my father’s invention, crushed milk-glass panels, made in Xenia, Ohio, sparkling when the sun cut through Midwestern cloud cover. Two years after the tower was completed, a tornado destroyed the town of Xenia and the plant where the panels were constructed. The panels were never used on any other building besides our home and this dormitory.

The only skyscraper outside of downtown, like an arrow on a compass, the gleaming tower could orient you even from miles away. “Oh, there’s campus,” you would say to yourself. While driving along Columbia Parkway edging the Ohio River, when the steep hills and wooded ravines tucked just right, you could catch a glimpse of the upper half of the tower, just for a moment.

That morning, everybody had their opinions of the building; the same rumors, questions and curses multiplied like flies, a cacophony of murmurs across every crowded hillside.

“There were fires in there. I heard someone died!”

“Some people tried smashing open their windows.”

“Did anyone jump?”

“Who ever would have designed such a thing?”

“A damned eyesore!”

Sander Hall took seven seconds to fall. Young voices cheered what might no longer be cheered, a chilling first practice in watching a modern glass-sheathed building shudder and wobble like a woman fainting or shot. Still managing to keep her dignity as she stayed upright, she sank to her knees before vanishing in a tsunami of dust that pursued the onlookers. Online you can play and replay four screens showing the single largest implosion in the Western Hemisphere. Five hundred and twenty pounds of dynamite carefully placed. Six months to plan. Seconds to fall.

On the houseboat, they raised their glasses to toast. White dust puffed gossamer between deep green hills where the tower had held the view for 20 years. My father said over the phone to me a week later, “Good riddance.” His voice still defiant. Interviews in the paper quoted him saying, “I still believe it was a perfect building. Even with all those fires set, a student never died in it.”

Yet I imagined him looking down, tracing his foot along a seam in the deck, muttering quietly, “It’s a terrible thing to outlive your buildings.”

Elizabeth Garber’s memoir will be available in June 2018. She is the author of three books of poetry, and three of her poems have been read on NPR on The Writer’s Almanac. She has maintained a private practice as an acupuncturist for over 30 years in midcoast Maine, where she raised her family.

LINKS:

As editor of UC Magazine, John enjoys the opportunity to put a human face on a large institution by telling compelling stories of the University of Cincinnati's incredible community of alumni, faculty, staff and students.

Additional Credits: Thanks to author Elizabeth Garber, designer Ben Gardner as well as web developers Kerry Overstake and Carolyn Noe for helping to develop and present the content contained in this piece.

FEATURES

Inspired by her mother, DAAP alumna launches clothing line for women recovering from breast surgery.

The 1991 implosion of UC’s Sander Hall continues to reverberate with the upcoming release of a powerful new book about the building’s architect from the perspective of his daughter.

Matt Berninger and Scott Devendorf of alt-rock band The National reflect on their formative years at UC.

UC’s new high school ambassador program could serve as a national model for helping low-income and first-generation students attend college.

How a local man gained precious time with his family thanks to innovative UC cancer treatment.

Leading urban public universities into a new era of innovation and impact.