“Better come. Hit bronze.”

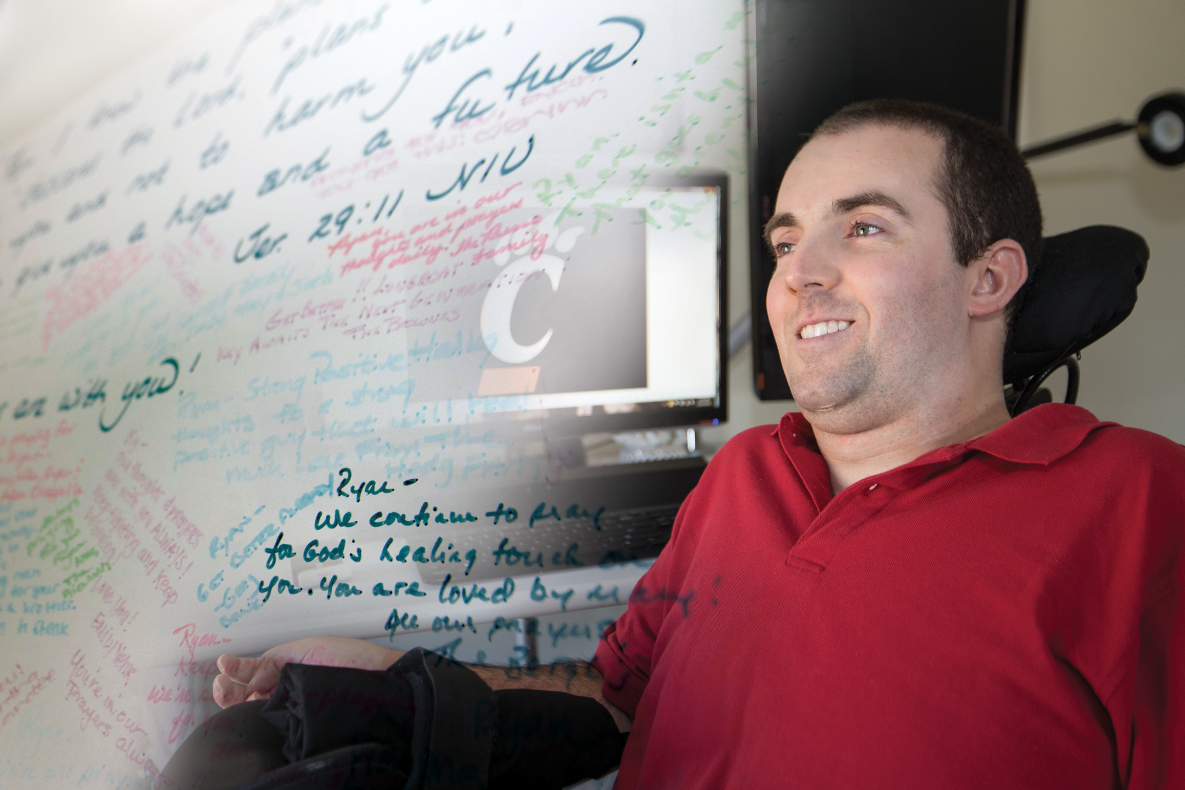

That urgent text message thumbed by their trench supervisor brought University of Cincinnati archaeologists Sharon Stocker and Jack Davis racing on foot to a dig they were leading last summer in southwestern Greece.

The husband-and-wife team knew the message mattered. And because of it, they were among the very first to inspect a spouted, Bronze Age basin that had last been held by human hands 3,500 years ago. It was their first find in what turned out to be an unexpectedly rich tomb of a prehistoric warrior buried at the dawn of European civilization.

Ultimately, according to Stocker, what had been planned as a six-week summer dig transformed into a nearly five-month “turtle’s marathon” of an excavation carried out in great secrecy, with round-the-clock security. Most of the excavation was painstakingly performed with wooden souvlaki sticks (the slender, pointed skewering sticks used for kebabs) as opposed to metal tools in order to safeguard the fragile finds.

At the bottom of the grave shaft lay the 15th century B.C. skeleton of a warrior buried with more than 1,400 objects, including jewels, weapons and armor, as well as bronze, silver and gold vessels. The team found the items on and around the body, along with an elaborate yard-long bronze sword, its ivory hilt covered in gold.

Gold cups rested on the warrior’s chest and stomach, and near his neck was a perfectly preserved gold necklace with two pendants. By his right side and spread around his head were over a thousand beads of carnelian, amethyst, jasper, agate and gold. Nearby were four solid-gold rings and silver cups as well as bronze bowls, cups, jugs, basins and dozens of intricately carved seal stones.

It’s been since the 1950s that such a wealthy tomb has come to light.

The rare results might seem a lucky strike, except the find in Pylos, Greece, is in an area where Stocker and Davis have worked for 25 years and where famed UC archaeologist Carl Blegen initially uncovered (and later excavated) the remains of the famed Palace of Nestor in an olive grove in 1939. In fact, this summer’s find was located in a previously unexplored field next to this best-preserved Bronze Age palace on the Greek mainland.

“We put a trench in this one spot only because three stones were visible on the surface. It was not particularly promising,” says Davis, adding, “At first, we expected to find the remains of a house, maybe from the medieval period. Then, we expected that this was the corner of a room of a house, but then realized that it was the tops of the walls of a stone-lined grave shaft.”

They began to dig. And found nothing.

A week passed.

They dug for a second week. Nothing.

And, paradoxically, the deeper they dug without results, the higher their hopes.

“We were digging for about two weeks and finding nothing, no objects near the surface. That meant we might have an exceptional prize: an undisturbed grave shaft never stripped by looters, even though the likelihood of such is vanishingly small. Whatever was waiting at the bottom had been sealed for millennia,” recalls Stocker.

The rarity of this rich find makes it all the more important to understanding a key, transformative moment in the Bronze Age.

The warrior lived in the pre-dawn of the Mycenaean civilization, which later gave rise to classical Greece. The Mycenaeans, however, were first influenced and inspired by the Minoan culture of the island of Crete, which was a two days’ sail south of Pylos.

Many of the tomb’s objects are thought to have been made in nearby Crete and show a strong Minoan style and technique unknown in mainland Greece in the 15th century B.C. According to the researchers, this wealth of jewels and weapons represented the best the Minoan culture had to offer. Thus, they suspect the unknown warrior may have been part of, and integral to, the cultural transition from Crete to Mycenae to classical Greece.

Explains Stocker, “The warrior, who died at about age 30 or 35, is likely an important figure at a time when this part of Greece was being indelibly shaped by close contact with Crete, Europe’s first advanced civilization.”

Davis is optimistic that further research will be able to pinpoint his identity as well as deepen the understanding of the relationship between Minoan and Mycenaean cultures at this pivotal time in history.

“It’s almost as if the warrior wants his story to be told,” Davis says.

Read international news coverage

MB Reilly

MB is director of public relations at the University of Cincinnati and a contributor to UC Magazine. She can be reached at 513-556-1824; mary-bridget.reilly@uc.edu

Additional credits: Digital design by Kerry Overstake and John Bach.