With Pluto well in its rearview mirror, New Horizons continues its decade-long adventure into the Kuiper Belt with a UC graduate still enjoying the ride.

As the space probe hurtled toward Pluto in what would give the world its clearest-ever glimpse of the mysterious dwarf planet, the unthinkable became reality.

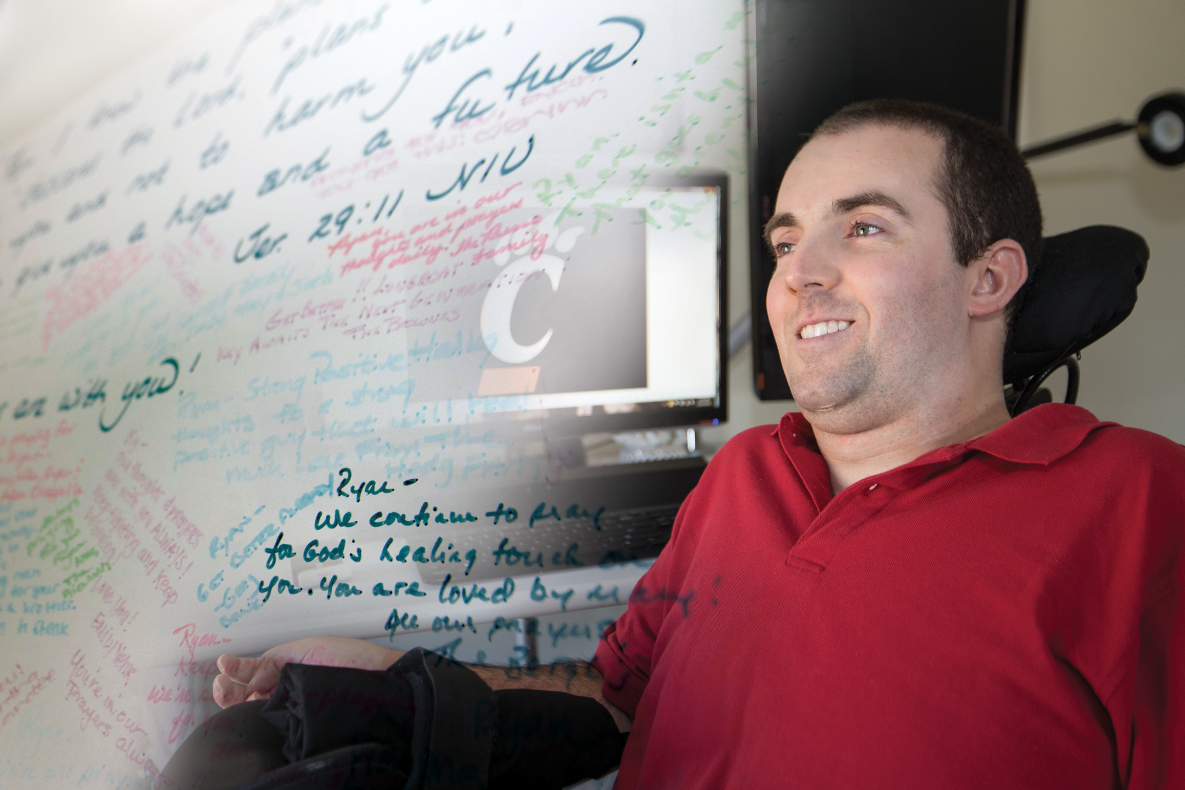

“This is my life’s work, and then 10 days before coming to fruition, I had my worst nightmare,” says New Horizons mission systems engineer Chris Hersman, Eng ’88. “It was 48 hours of terror.”

The date was July 4, 2015, not quite a decade after the probe, which is the size and weight of a grand piano, was flung into the cosmos to study and photograph one of the solar system’s farthest outposts. Suddenly, and without explanation, Hersman and his team lost communication with the craft.

Nervous moments turned into a two-day race to find the cause of the blackout and avoid missing the start of the nine-day “encounter command sequence,” in which New Horizons would snap photos of Pluto and collect atmospheric data. In the end, Hersman and his colleagues at mission headquarters, Johns Hopkins University’s renowned Applied Physics Laboratory, regained transmissions — with a scant 12 hours to spare.

The fix was simple, although the problem, or anomaly, as engineers are wont to say, wasn’t anything for which Hersman and his colleagues had planned. The craft’s computer had become overloaded when its earthbound operators sent it Pluto flyby instructions at the same time the computer was compressing data to make room for new information.

“It was essentially a software conflict,” says Hersman, whose job is to ensure that all technical aspects of the mission run smoothly. “They were operations that shouldn’t have taken place at the same time.”

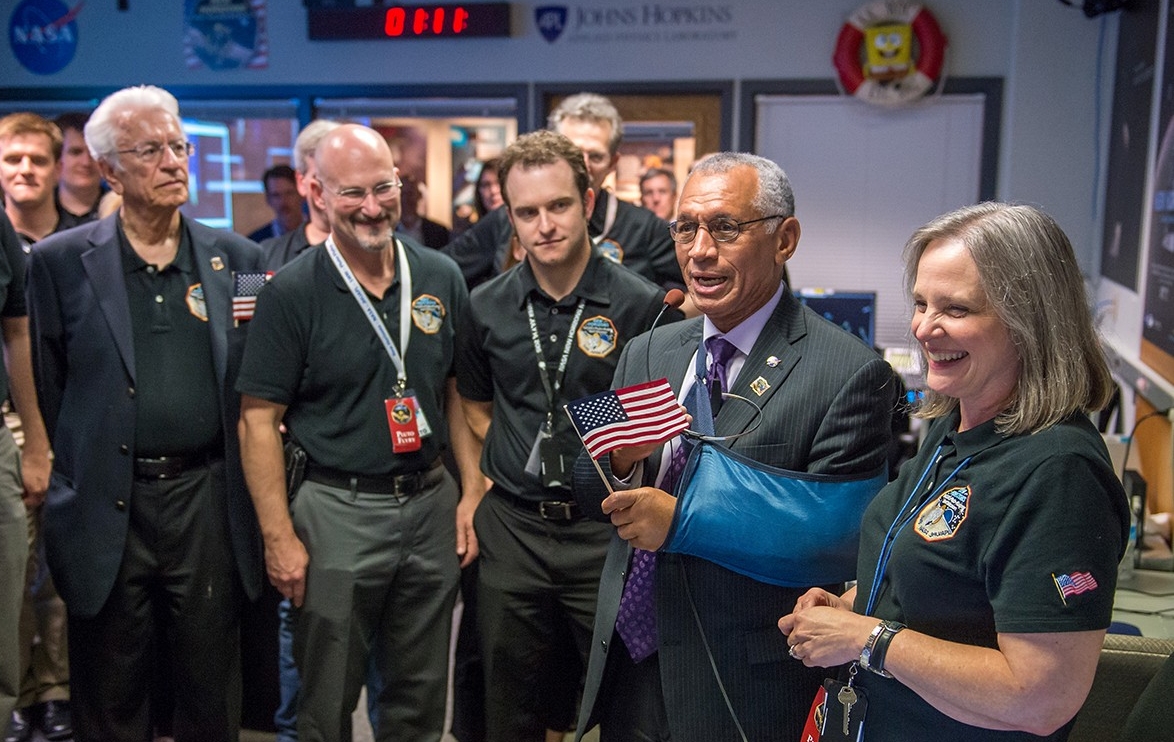

Chris Hersman, a 1988 graduate of UC’s College of Engineering and Applied Science, uses a model of New Horizons to explain how he and others have been able to guide the craft to (and past) Pluto since the mission launched in 2006. Photos/NASA/JHUAPL

The episode played to his strengths, according to those who know him. Not only does Hersman embody a natural equanimity, but he also possesses a knack for rooting out the source of trouble, notes Alice Bowman, the mission’s operations manager.

“Chris has the ability to focus on the minute details of what’s going on,” Bowman says. “When there’s a problem on the spacecraft, he leaves no stone unturned. Which is a huge benefit, because many times what you see on the surface is not necessarily the root cause of the problem. And he’s very cool under pressure.”

For Hersman, the Pluto mission is the culmination of a lifetime of tinkering and scientific inquiry. He was on the team that proposed the mission in 2001, part of NASA’s New Frontiers program to develop missions to study Jupiter and Venus, in addition to Pluto.

Watching the Apollo moon missions as a kid wasn’t the only factor that fired Hersman’s imagination and propelled him into a career as a space-age electrical engineer. Growing up in suburban Greenhills, just north of Cincinnati, he began disassembling unusable televisions and radios as a teenager. Trying to figure out how things worked became a way of life. He even wowed UC friends with his quizzical creations.

Hersman lived in Calhoun Hall with childhood pal and roommate Sean Keith, Eng ’88, a chemical engineering major who now is an executive with GE Aviation. The pair built a loft on which they could perch their beds to create more floor space. But there was one problem. Neither man could reach the light switch once they were in bed.

Hersman took it upon himself to find a solution. He rigged a whistle switch to a lamp, which allowed the roommates to extinguish the light by whistling or by clapping loudly.

It should be noted that Hersman’s creation came a full three years before the Clapper, which performed a similar function, went to market. That device became a pop culture sensation when it was hawked for years on daytime TV. “Chris invented the Clapper on his own,” Keith insists to this day. “He wanted to do things that nobody else was doing.”

Hersman also installed a doorbell outside their seventh-floor doorway. He added to his quirky appeal by riding a unicycle in the hallways of the dormitory.

“He was so smart, he was almost operating on a different level,” says Keith, who gushes about his friend’s brainy feats.

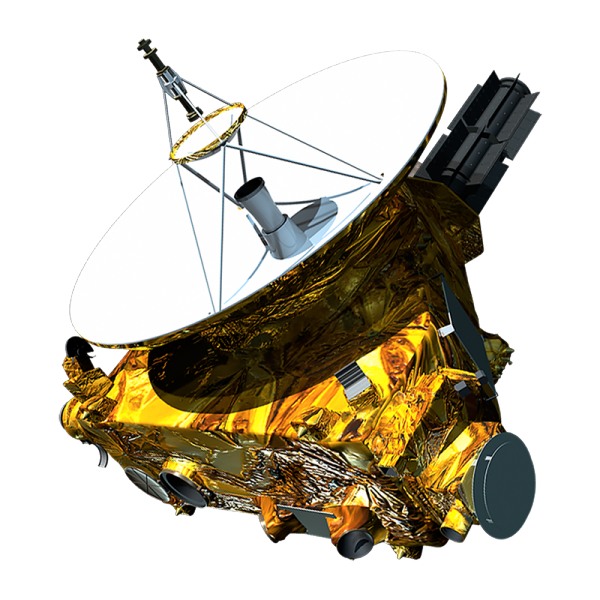

The New Horizons mission launched January 19, 2006. photo/NASA/JHUAPL

“It’s a source of pride for me to know Chris and what he’s accomplished.”

It was at UC, where Hersman got his undergraduate degree in electrical engineering, that he would learn the maxim that continues to inform his work: Test as you fly, and fly as you test. In simplest terms, the adage, subscribed to widely by NASA engineers, means ground tests and simulations should accurately reflect the planned mission.

Wavering from a plan can have disastrous effects, as Hersman can attest. Luckily for him, his early misfortunes came with much lower stakes: as a participant in the college’s egg drop contest. From a balcony at Rhodes Hall, students attempted to lower a raw egg to a target 20 feet below. They could employ whatever methods they saw fit to keep the egg intact.

Using fishing line, pulleys and an improvised egg “hammock,” Hersman figured his own plan was foolproof. Until the day of the competition, when he decided to use thicker fishing line. He assumed the extra tensile strength would improve his chances for success.

“My friend who was working with me asked, ‘Are you sure we should change anything?’ I said ‘Yes, I know what I’m doing,’” Hersman recalls with a now-knowing laugh. “I rewired the larger line and, sure enough, when we went to do it, the line was a little bit too big and it jammed in the system of pulleys.”

The effort ended with a splat. But it taught Hersman a critical lesson.

“Ever since then, I realized you don’t change something after you test it,” the engineer says. “Even though it was a small consequence at the time, it was very important to test as you fly.”

New Horizons team celebrates the probe's arrival at Pluto.

The New Horizons mission, by all accounts, has been a success beyond anyone’s wildest imagination. Except for the Independence Day scare, the voyage has gone nearly flawlessly. But leave it to Hersman and his team to quibble. New Horizons arrived in Pluto’s neighborhood 7,750 miles above the surface of the dwarf planet, 50 miles lower than planned. The probe also arrived 90 seconds early.

“We’re engineers. We’re our worst critics,” jokes mission manager Bowman. “Still, when you think of Pluto being about 3 billion miles from Earth, it’s amazing that we have the technology to hit something that far away with that kind of accuracy.”

Hersman says it was the first picture of Pluto beamed to mission control after the communication breakdown that remains his most memorable.

Guests and New Horizons team members countdown the spacecraft's closest approach to Pluto on July 14, 2015. Photo/NASA/JUAPL

“It wasn’t even the best image, but we had been working frantically, and I was completely exhausted from all of the activity,” he says. “To see that image, it was just a relief to know that everything was working.”

But as the pictures kept coming, bigger and with better resolution, Hersman joined in the collective awe that gripped the Johns Hopkins lab.

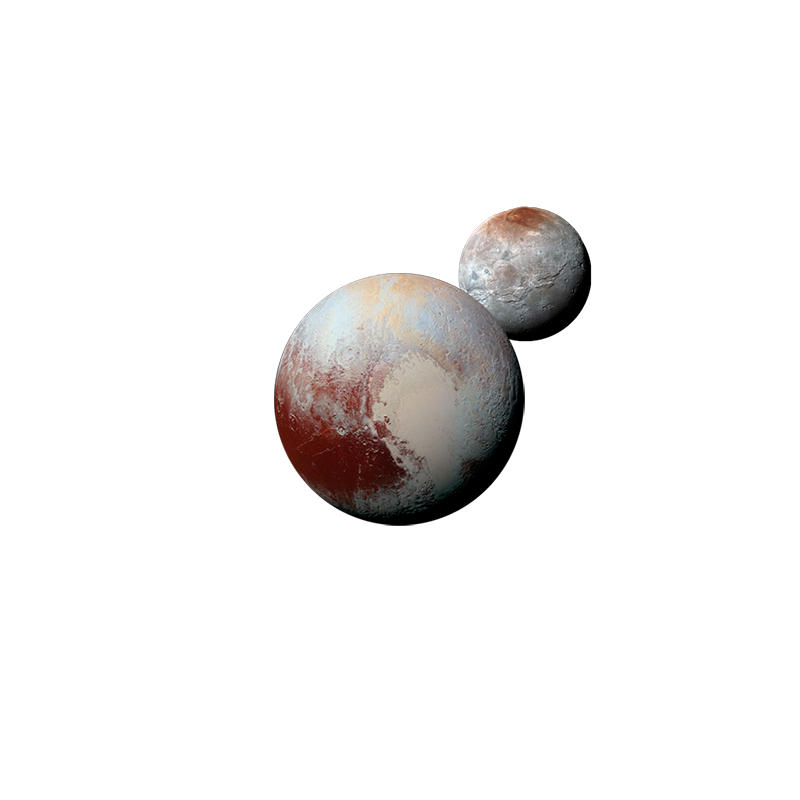

Images were both epic and sublime. Pluto revealed itself as a place of wild contrasts. Icy plains give way to mountains towering to heights of 11,000 feet. A separate image showed Pluto’s heart-shaped region, called the Tombaugh Regio, named after the astronomer who discovered the then-planet in 1930.

Hersman says he’s thrilled by what the mission has accomplished so far. “It’s like we’re writing the science books.” He doesn’t dwell on a 2006 resolution by the International Astronomical Union. The group released its document just six months after New Horizons’ launch, a report that demoted Pluto to dwarf planet status because its mass is too small to exert gravitational pull on other celestial bodies.

“There are children I meet who will say, ‘Don’t you know Pluto doesn’t exist anymore?’” Hersman says. “I’m not one to fight that battle. To me, it will always be planet No. 9. I joke that we haven’t told the spacecraft yet that Pluto was demoted.”

New Horizons is already on to farther-flung pursuits. As of early March 2016, it was 174 million miles beyond Pluto and en route to another minor planet known as 2014 MU69, discovered in 2014 by the Hubble Space Telescope. The craft is expected to make that flyby around Jan. 1, 2019.

Like Pluto, MU69 sits in the Kuiper Belt, the massive region that extends beyond Neptune, which supplanted Pluto as the solar system’s farthest planet from Earth. The belt is thought to contain numerous comets, asteroids and icy bodies, as well as remnants of the solar system’s formation.

Discoveries will help scientists better grasp the evolution of the solar system. If Hersman has his way, New Horizons will survive for up to 30 years, when space radiation could finally wear down the spacecraft’s electronics and send it to eternal rest.

“We’ve just got to make sure we keep everything on the spacecraft as warm and functional for as long as we can,” says Hersman, who clearly is enjoying the ride. “I hope I’m here when it’s time to turn out the lights.”

Ten Years & Three Billion Miles

EARTH

January 19, 2006

New Horizons spacecraft launches from Cape Canaveral, Florida aboard a fast-moving Atlas V rocket as it headed for a distant rendezvous with the mysterious planet Pluto. Its journey to Pluto will nearly equal 32 trips between Earth and the sun.

JUPITER

February 28, 2007

Spacecraft flies by Jupiter for a gravity assist that saves three years of flight time. The team conducts significant science in preparation for the Pluto encounter. For most of the eight-year cruise from Jupiter to Pluto, the craft spins slowly in a state of “hibernation,” signaling once a week to assure it’s “sleeping peacefully.” But for about 50 days each year, it is awakened to conduct an intensive set of spacecraft and instrumental checks as well as navigation measurements to verify the spacecraft is on course.

PLUTO

December 2014

The spacecraft is awakened from its final planned hibernation. Intensive preparations for the Pluto encounter continue.

July 15, 2015

New Horizons makes its closest approach to Pluto capturing stunning images of the icy planet. Generally, New Horizons seeks to understand where Pluto and its moons “fit in” with the other objects in the solar system, such as the inner rocky planets (Earth, Mars, Venus and Mercury) and the outer gas giants (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune).

2017-2020

With NASA’s approval, New Horizons can explore suitable, recently discovered Kuiper Belt objects beyond Pluto. The spacecraft will potentially examine one or two of the ancient, icy mini-worlds in that vast region, at least a billion miles beyond Neptune’s orbit.

Andrew Faught is a freelance writer who contributes to UC Magazine.

Additional credits: Graphic design by Rebecca Sylvester and Kathy Bohlen. Motion graphics web development by Ben Stockwell. Digital design by Kerry Overstake and John Bach.