Marijuana-based epilepsy drug shows real promise for patients and families desperate for relief.

By Alison Sampson

Photos by Colleen Kelley

At 26 years old, William Plott must wear a helmet. His room is padded, and when the seizures were at their worst, his mom even dressed him in padded hockey pants.

Glenn and Cass Plott say their son, who is nonverbal, has experienced frequent epileptic seizures since he was six months old.

For years, William saw specialists at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, but the hospital system encourages patients to graduate to adult-focused care by age 24. So when William was ready to age out of Children’s, it was with trepidation from the Plotts. They weren’t sure what a transition to UC Health’s University of Cincinnati Epilepsy Center would mean for their family.

William began seeing Dr. David Ficker, a professor at the UC College of Medicine and a neurologist specializing in epilepsy with the UC Epilepsy Center within the UC Gardner Neuroscience Institute.

In search of answers and relief, the family has been through what they refer to as “a drug odyssey.” Å

“When he was younger, he spent hours a day in seizures,” explains Glenn. “It’s been a struggle to find something that doesn’t take your child away. Sure, you can stop the seizure, but then he’s comatose, and what kind of life is that?” They describe a series of drugs through the years with “really ugly” side effects. Some require injections. Some cause hunger. Others can cause vomiting or risk of severe liver damage.

It’s been a struggle to find something that doesn’t take your child away."

A new path forward

On their third visit to UC in October 2015, Ficker, A&S ’88, Med ’92, suggested a new trial involving a pharmaceutical medical marijuana derivative called Epidiolex that was being tested for the reduction of seizures.

More than a year later, that suggestion, as it turned out, has made all the difference for William, who now experiences fewer and less intense seizures.

“We reviewed his history when we first met, and he had quite an extensive evaluation and treatment with a number of different medications,” says Ficker. “So sometimes it can be a challenge to offer patients something new in the way of treatments.”

Doctors had just started enrolling patients into the Epidiolex study to determine the medication’s effect on “drop seizures,” which are associated with a sudden fall and often lead to injuries.

The Plotts had read about Charlotte’s Web, a marijuana-derived, high-cannabidiol (CBD), low-THC supplement that was gaining popularity in Colorado for treatment of seizures. “We even had the ‘Colorado talk’ a couple times, like, ‘Could that work for William?’” says Cass.

UC Epilepsy Center Director Michael Privitera, a professor of neurology at the UC College of Medicine and a UC Health physician, had been talking to colleagues and researchers at other universities, also wondering “what if.” Privitera had also heard, anecdotally, the stories about CBD oil as a treatment for epilepsy but had some skepticism, as the results were mixed, and there wasn’t an FDA-approved study.

William wears a helmet because of his frequent and unpredictable “drop seizures.”

Dr. Michael Privitera, director of the Epilepsy Center at the UC Gardner Neuroscience Institute, is leading the local trial for Epidiolex. The drug manufacturers will apply for FDA approval this year.

Still interested, he consulted with a colleague at New York University, Orrin Devinsky, who was conducting a trial with Epidiolex, a pure CBD oil without THC, in patients with severe childhood-onset, treatment-resistant epilepsy. THC causes the “high” from marijuana use.

“If I was going to recommend something like this to my patients, I wanted to be able to prescribe an FDA-approved pharmaceutical with no concerns about impurities, consistent dosing or expiration dates,” says Privitera. “These are things that we expect for any medication we take.”

But setting up a trial with a drug federally classified as Schedule I, “with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse,” meant navigating through both the FDA and the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

Privitera describes the process as more arduous than any other clinical trial he has ever done, including nine months of regulatory paperwork and obtaining licenses for approval, individual ordering and shipment of the drug for each patient, clearing it in the U.S. by the DEA and then shipping it to Cincinnati, where it was stored in a large safe and heavily scrutinized during the reconciliation process.

Conversely, Privitera says, patient enrollment was a breeze. “Easiest trial I’ve ever filled,” he says.

William was one of those first 12 participants in Cincinnati, beginning the trial in December 2015 in a double-blind phase — neither the patient nor the doctors or researchers know who is receiving the drug and who is receiving a placebo. The Plotts, however, were pretty sure that William was not experiencing a placebo effect.

“The first thing that happened, and we kind of laughed about it — he got really hungry. Like the munchies,” recalls Glenn. “He put on about 5 pounds.”

But as they’ve experienced with any new treatment, it was a bit of a roller coaster. He was hungry, then had no appetite. He was very sleepy and lethargic and then excitable and anxious. The doctors discovered the new drug was interacting with his Onfi, another common epilepsy drug treatment, and adjusted it to keep him on the trial.

Glenn, William and Cass Plott outside their Westwood home in Novemeber 2016.

For years, the Plotts kept careful logbooks of everything, specifically a tally of William’s daily seizures, which would average 400 to 450 per year. A page in the seizure logbook was usually filled in a week. Then, on the new treatment, it took three weeks; then, five.

“Now, the frequency of the seizures has gone down so much,” Glenn says, “and he’s behaving differently. He’s more aware of his surroundings, more cognizant of people, a little more playful and also a little more mischievous.”

Cass agrees. “He’s playing with objects differently, he’s exploring his world in a different way.”

His doctors concur.

“William’s changes in cognition are outcomes we didn’t account for or look for in the study,” explains Ficker. He points out that frequent seizures have been linked to cognitive problems, so reducing frequency may also impact behavior and cognition.

Either way, the Plotts are pleasantly surprised at the changes. And overall, the trials have performed well. Patients experienced on average a 40 percent median reduction in monthly drop seizures, compared with 17 percent of those on a placebo.

Dr. David Ficker is a professor at the UC College of Medicine and a neurologist specializing in epilepsy with the UC Epilepsy Center within the UC Gardner Neuroscience Institute.

Of the patients who completed the trial, 99 percent — including the Plotts — have opted to continue into an open-label extension trial with Epidiolex treatment. Officials say findings will be submitted to the FDA this year to begin the process that could eventually lead to FDA approval

“When we got into this trial, Cass and I talked about it and decided, even if it didn’t help [William] or we couldn’t see it all the way through, we saw that our participation could help someone else,” says Glenn.

But now, with Epidiolex, it’s something they hope will not only be available to them in the future, but available to others as well.

“We’ve found a good thing, and we don’t want it to go away.”

Alison Sampson is a public information officer at the University of Cincinnati and contributes to UC Magazine. sampsoam@ucmail.uc.edu

FEATURES

UC law professor and co-founder of the Ohio Innocence Project reflects on 24 wrongly convicted individuals.

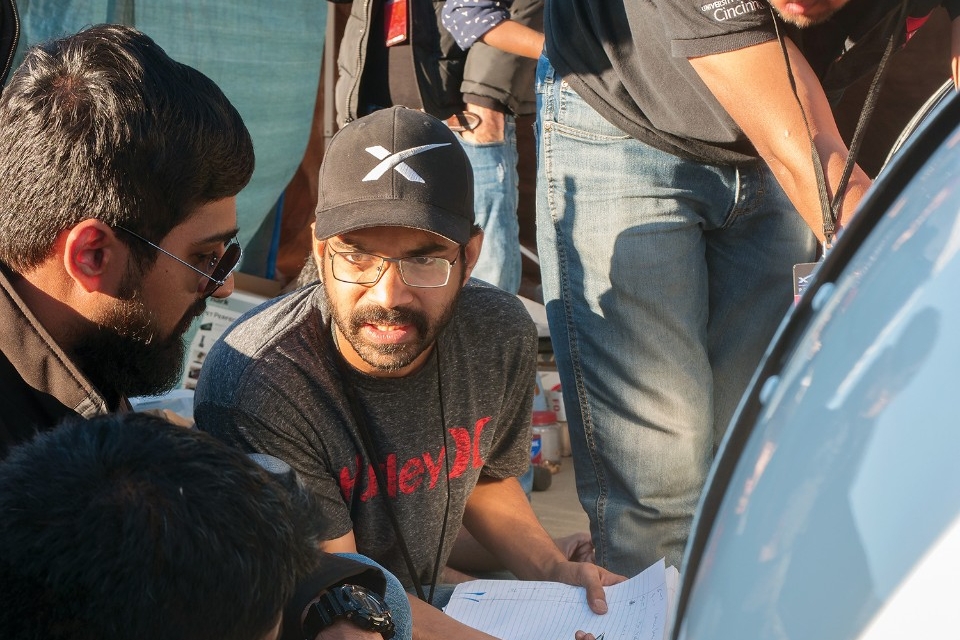

UC student team tests finalist prototype at Elon Musk’s worldwide Hyperloop competition.

ArtWorks and UC have enriched Cincinnati’s cultural landscape with public art for more than two decades.

How a former Bearcat overcame a brush with death, got drafted by the Reds and turned a school bus into a home.

UC doctor leads trial of marijuana-based prescription drug showing real promise for epilepsy patients.

Building a better Business School

UC breaks ground on a new $120 million home for the Carl H. Lindner College of Business.