Sisters Lucy (left) and Annette Braun at Beechwood Camp in Hueston Woods, Ohio, in 1910. photo/Courtesy of W.S. Turrell Herbarium, Miami University

Sisters Lucy and Annette Braun, UC’s trailblazing female PhDs, devoted their lives to illuminating nature

by Elissa Yancey

Photos by Lisa Ventre, and courtesy of the Cincinnati Museum Center and the W.S. Turrell Herbarium at Miami University

Decades before two University of Cincinnati alumnae became the groundbreaking women STEM researchers known around the globe for their passion for nature and conservation, they spent happy childhood days scrambling into a horse-drawn streetcar that took them from their home in Walnut Hills to the forested wilds of Rose Hill in Avondale.

There, before the turn of the 20th century, young Annette Frances and Emma Lucy Braun followed their naturalist parents on expeditions to collect leaves and flowers and examine trees. As they marveled at the beauty around them, their parents made sure they also learned the Latin names of every plant they collected. And as they explored, they developed a lifelong appreciation for the connection between trees and plants, between soil and species, and between humans and the natural world.

Those were lessons that the Woodward High School graduates took with them to the University of Cincinnati, where Annette, at age 26, became the first woman to earn a doctoral degree. The year was 1911, five years after the founding of UC’s graduate school and nine years before women in America gained the right to vote.

When Annette had first enrolled in 1902, the number of American women with doctorates in science was estimated in the dozens — and nearly all of those had graduated from all-female universities.

Lucy, younger than Annette by five years, received her UC master’s degree in geology in 1912 and her doctorate in botany in 1914. She was the second woman in science to earn the college’s highest degree and just the third woman to do so overall.

Both Brauns were standout students. They received the College of Liberal Arts’ most prestigious academic scholarships. They were also founding and guiding members of the university’s oldest academic club, the botany-focused Blue Hydra Society.

The society’s mission echoed both the lessons of the Brauns’ youth and the teachings of their faculty mentor, botany professor Harris Benedict: Only through close and reverent examination of nature can humans understand and protect its beauties and wonders.

BLAZING TRAILS

The sisters’ research paths were complementary: Annette studied insects; Lucy pored over plants. Annette found satisfaction in collecting and identifying the tiniest of moths whose mission to pollinate the plants kept ecosystems thriving; Lucy, who coined the term plant ecology to describe her work, took special interest in the forests of Ohio and Kentucky. She developed revolutionary new theories about how mixed forests in the Midwest came to be and why they were important to protect.

After Annette left UC, she continued her research, amassing more than 30,000 microlepidoptera — or “smaller moths” — from around the world. For years, the Brauns shared a home with the country’s second largest collection of moths. Annette regularly assisted experts at the U.S. Department of Agriculture and researchers throughout Europe, Canada and Africa.

Lucy stayed at UC and helped Professor Benedict build the botany department. Thirteen years after her first appointment at UC, Lucy received tenure, a rare accomplishment for any woman in science, in 1927. When Benedict died in an accident in 1929, Lucy led the department for a year, but her heart remained in the field, in places like Ohio’s Adams County, where she regularly took students on weeklong research trips.

She longed to spend more time untangling the mysteries of forest species that glaciers had left behind and geology had helped preserve. With Annette’s support, Lucy compiled what would become her masterwork, “Deciduous Forests of Eastern North America,” in 1950. More than 60 years later, the book remains the authoritative source on the subject.

Lucy Braun looks across landscape from the Serpent Mound observation tower located in Adams County, Ohio, in 1937. photo/Courtesy W.S. Turrell Herbarium, Miami University

"Only through close and reverent examination of nature can humans understand and protect its beauties and wonders."

PLANTING SEEDS

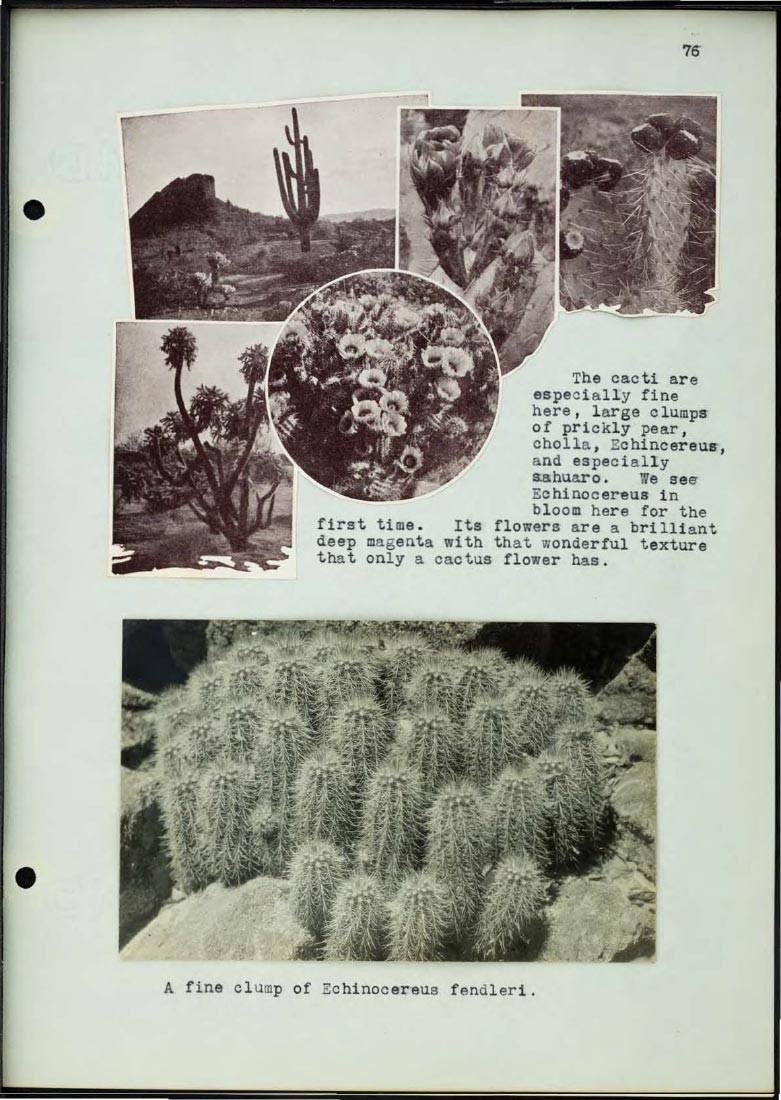

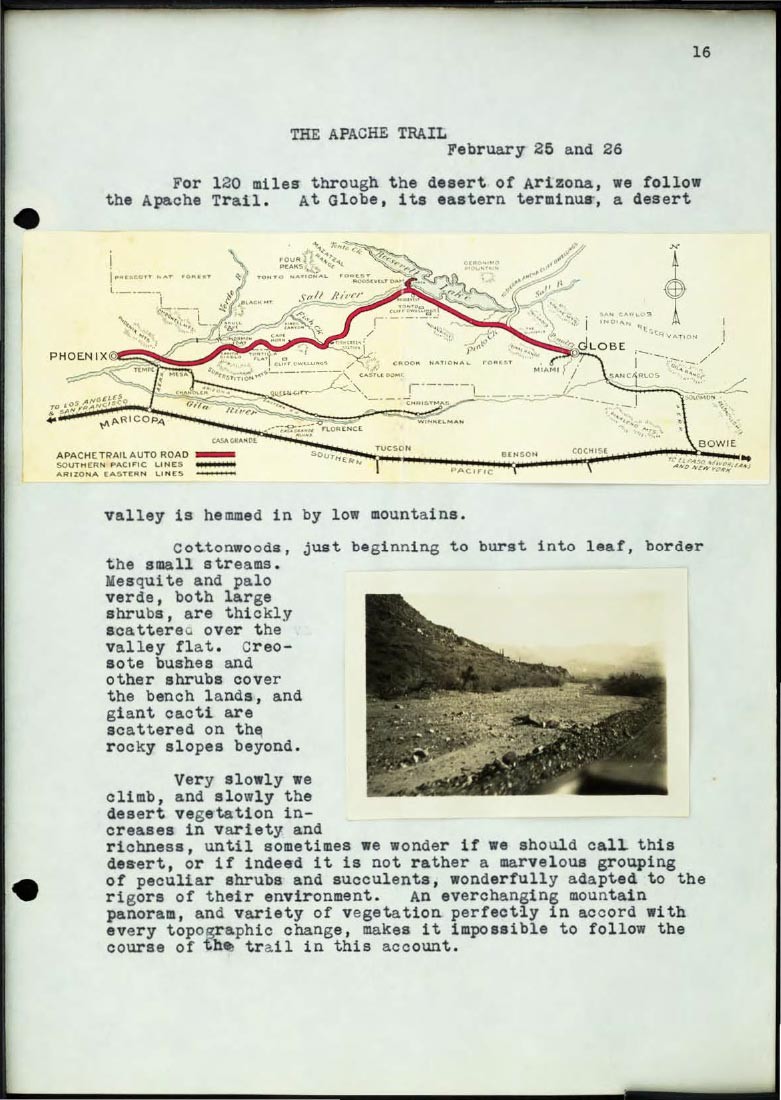

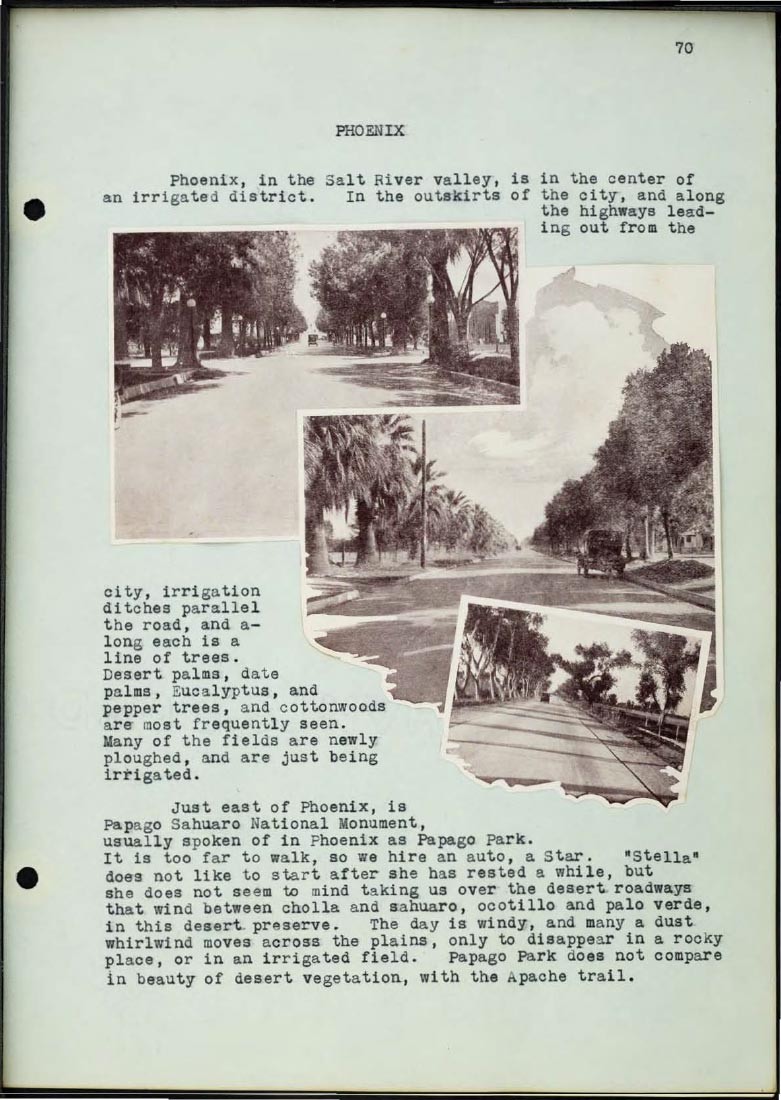

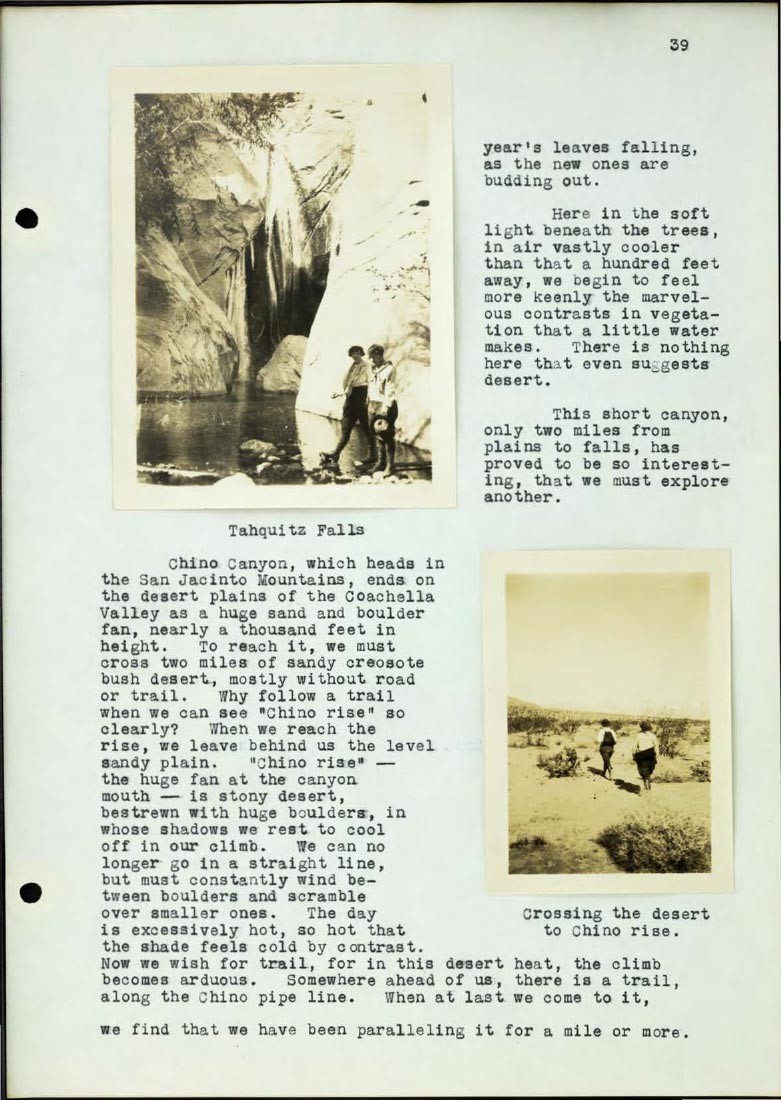

Just as they had in childhood, Annette and Lucy made a great team in the field. As women scientists, they traveled where neither could have succeeded alone, from moonshiner strongholds in the Kentucky Appalachians to the base of the Grand Canyon. After decades of traveling via train, coach and horseback and logging hundreds of miles on foot, Lucy bought a car in 1930, and the sisters explored like never before. In their more than 65,000 miles of travel, Lucy took thousands of photos and wrote hundreds of letters while Annette collected samples, packed lunches and spent days perfecting drawings of her near-microscopic specimens.

The sisters’ exhaustive knowledge and artistic prowess filled illustrated journals, and Lucy inspired generations of students who delighted when she allowed them to “discover” species on hikes. Some of those students, like Margaret Fulford, who earned her doctorate from Yale in 1935 after earning three degrees at UC, came back to Cincinnati to research or teach, training future scholars. But their influence isn’t limited to the past.

“The work of the Braun sisters changed the course of my studies and the direction of my life,” says Brittney Conover, who received her bachelor’s degree in biology from the McMicken College of Arts and Sciences in 2017 and works as a plant cataloger at UC’s Margaret H. Fulford Herbarium in Crosley Tower. She is a member of the current Blue Hydra Society, which reclaimed its original name in 2016. “After reading through Lucy’s books, I discovered that I have a love for forest ecology.”

The Brauns’ devotion to their research was absolute. Neither married, and when they moved to Mount Washington in 1944, they dubbed their stone farmhouse “Braunwood.” They turned the second floor into their laboratory and their yard into an experimental garden. Though Lucy officially retired in 1948 and was named an emeritus professor, she continued to receive federal funding for her research and lead hikes until 1970, the year before she died at 81. Annette died in 1978 after turning 94.

MAKING HISTORY

During the prime of her research and publishing career, Lucy grew determined to protect native forests from both development and invasive species. She and Annette fought for years to save Leatherwood Forest in Eastern Kentucky, where massive tulip trees grew to heights of more than 125 feet, only to have it cleared by a lumber company in 1938. Perhaps, Lucy mused, their fight had at least raised some awareness of the importance of conservation.

As she received national honors for her research and gained prominence as the first woman to hold a range of high-profile scientific leadership positions, Lucy never tired of sharing her discoveries and promoting preservation. She helped found the Wildflower Preservation Society of North America, led the Cincinnati chapter and edited its national journal, often sprinkling romantic nature poems by William Wordsworth and William Cullen Bryant between more scientific articles.

But it is in the mixed forest and prairie lands of Adams County that the Brauns left their most significant ecological legacy: the 19,000-plus acre Edge of Appalachia Preserve. With support from former students Richard and Lucile Durrell, Lucy enticed the Nature Conservancy to purchase the first parcel of the preserve in 1959.

Visitors to the preserve today can wander the E. Lucy Braun Lynx Prairie and rest on Annette’s Rock thanks to the turn-of-the-20th-century STEM girls whose dedication helped secure the untouched wilderness.

The Journals of Lucy Braun

Courtesy DeVere Burt

FEATURES

UC grad helps fight stigma of mental illness by sharing her own journey from schizophrenia to recovery.

Sisters Lucy and Annette Braun, UC's trailblazing female PhDs, devoted their lives to illuminating nature.

At 150 years, CCM reflects on its humble beginnings and impressive firsts while celebrating successful alumni and campus events.

UC’s All-American thrower became the fifth national champion in Bearcats history.

UC’s Richard Harknett, one of the world’s leading online security experts, reveals the digital threats that keep him up at night.

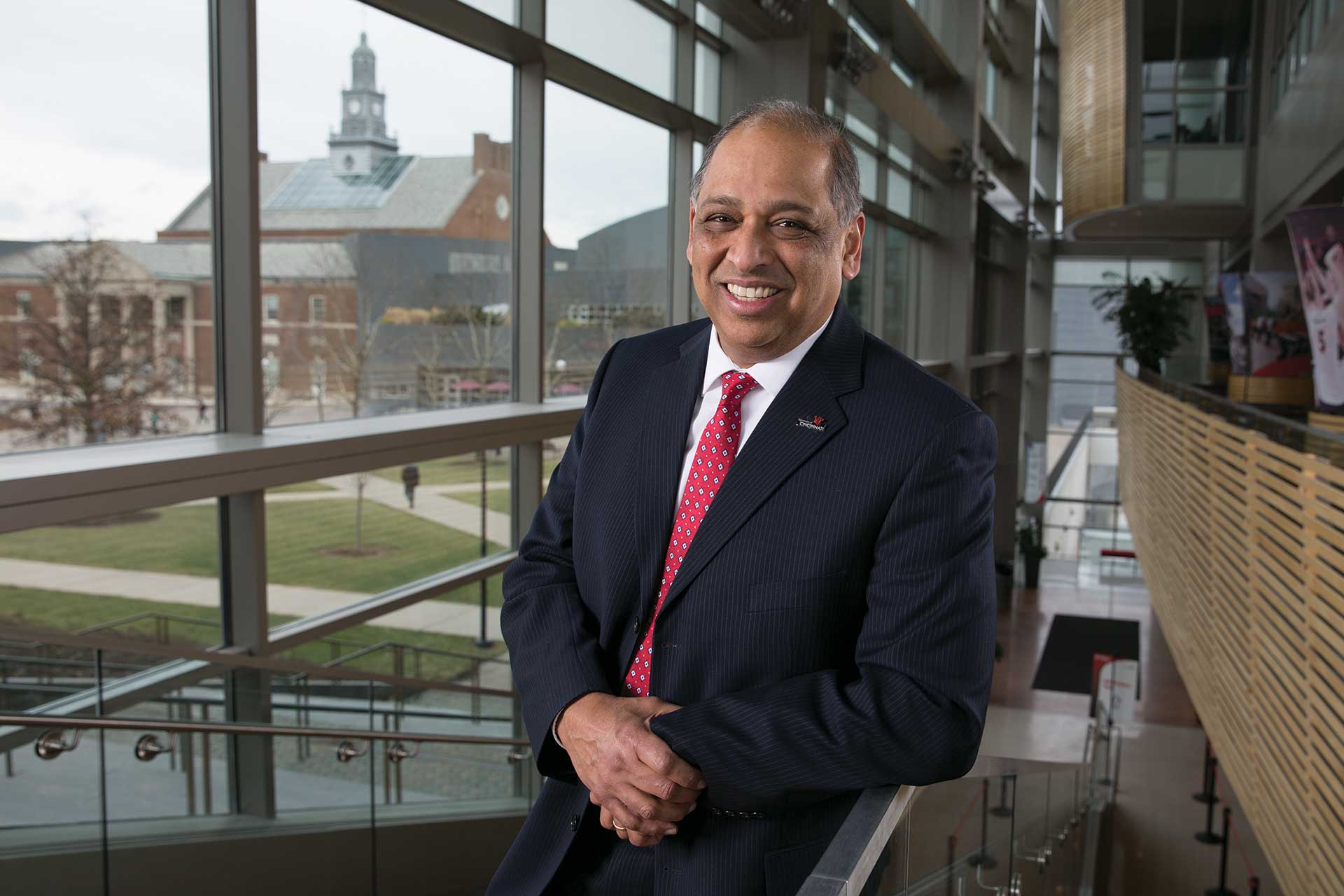

UC President Neville Pinto is back home at the university that launched his career. His mission: to promote the value of higher education.