UC’s Richard Harknett is one of the world’s leading online security experts, but you won’t find him on Facebook.

By Rachel Richardson

Photos by Lisa Ventre

Illustrations by Margaret Weiner

Y

ou’ve seen the headlines: massive cyber breaches at major corporations compromising the confidential information of millions; global ransomware attacks that hold critical systems and data hostage; well-orchestrated spear phishing campaigns devised to disrupt American national security interests; and large-scale distributed-denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks that take down websites of all sizes.

Add to that the surging levels of internet-based crimes that often don’t make the news, from cyberbullying to internet scams and identity theft. No longer the actions of a few rogue hackers, online attacks are now big business and today’s cyber criminals are more sophisticated, better resourced and increasingly more difficult to track down.

Enter Richard Harknett. For more than 25 years, the University of Cincinnati professor of political science has researched and advised senior government officials on how to protect against and deter threats, both real-world and cyber, in an interconnected world.

Harknett’s impressive resume includes cybersecurity briefings at the White House, Pentagon, U.S. State Department and Great Britain’s No. 10 Downing St. In the 1990s, he advised the Clinton administration on the development of critical cyber infrastructure before being appointed to Ohio’s Cyber Security Education and Economic Development Council.

In 2015, Harknett became the first scholar-in-residence for U.S. Cyber Command, an initiative of the Department of Defense, where he interacted with top American military and intelligence leaders to improve the nation’s cybersecurity policies. He most recently returned from England, where he had spent the past year as a U.S.-U.K. Fulbright Scholar in Cybersecurity at the University of Oxford.

An academic at heart, Harknett shrugs off the accolades. “I take very seriously the fact that we’re a public research university and that there’s a public service role for us,” he says.

FROM NUKES TO HACKS

The savvy political scientist began his academic career researching another global threat, nuclear weapons, before arriving at UC in 1991. Then, the Pentagon called him up.

“They said, ‘We got this thing called a browser. What do you think?’” says Harknett with a laugh.

For the next few years, Harknett shifted his focus from the specter of nuclear war to the nascent “informational warfare” threat, becoming one of the few social scientists in a field still dominated by techies. He had resumed his work on nuclear weapons when, in 2006, the government came calling again.

“The Department of Defense said, ‘Hey, you know all that stuff you did in the 1990s? Well, you were pretty much right. Could you reprise it for us?’” Harknett says.

We’ve struggled at the national level with how the government can provide national security when individuals themselves are a source of vulnerability.”

Harknett’s briefings and research contributed to preparations for the 2009 launch of U.S. Cyber Command and made him a sought-after authority on cybersecurity, having lectured at dozens of events in seven countries across the globe.

In 2014, Harknett helped steer the development of a new multidisciplinary cybersecurity certificate track at UC, geared toward students interested in public policy and strategy. The offering quickly took off — UC is one of just 16 universities in the nation designated by the National Security Agency as a National Center of Academic Excellence in Cyber Operations.

Amid the hodgepodge of threats dotting the cyber landscape, Harknett trains his sights on more looming issues involving national security: How can the U.S. develop a comprehensive and effective cybersecurity policy when the online infrastructure hinges on ease and accessibility even as cyber threats become more networked and globalized?

“We’ve struggled at the national level with how the government can provide national security when individuals themselves are a source of vulnerability,” says Harknett.

He offers an example: An unsuspecting user clicks on a malicious link, which then delivers malware to his computer. The hijacked computer is then organized into an enormous network called a botnet, a sort of online zombie army that can then be launched as part of a larger attack against websites and critical services.

“Now I’m able to shut down an electric grid,” says Harknett. “Your individual insecurity has had a national impact. That’s what keeps me up at night and worries me from a national security standpoint.”

Even more disturbing, cyber threats are no longer the domain of the technical elite. Now even amateur cyber attackers can purchase inexpensive turnkey toolkits that allow them to launch devastating digital attacks quickly and easily.

A NEW FRONTIER

The next cybersecurity battleground? Artificial intelligence, a fast-advancing Pandora’s box that its human wranglers risk losing control of, warns Harknett. He points to Facebook’s announcement earlier this year that it’s building a brain-computer interface that uses sensors to read your mind and translate your thoughts into readable text.

“If we’re building this on the same vulnerable system and infrastructure we have now, now we’re talking about giving access to hack brains,” says Harknett. “That’s not science fiction. We’re within a decade of having artificial super-intelligence and machine learning.”

“That’s all great if it functions according to its parameters,” he adds. “But we’re still at the first iteration of this technology. The vulnerabilities that come with it are a whole level of concern that we’re not even talking about in a public policy setting.”

If all this sounds like a doom-and-gloom scenario, Harknett points to a bright spot. Amid a desperate demand for cybersecurity talent, UC is already paving the way with skilled graduates ready and able to tackle the increasingly con-tested and volatile global cybersecurity risks in this new, more dangerous digital age.

7 WAYS TO PROTECT YOURSELF ONLINE

Cybercrimes and attacks are becoming more commonplace, more dangerous and more sophisticated, but there are simple ways to protect yourself, your privacy and your data. UC cybersecurity expert Richard Harknett offers these seven tips for keeping your online life secure.

- Think before you click. “Phishing still remains one of the easiest ways of being exploited,” warns Harknett. “You have to be skeptical about everything that you click on.” One easy way to tell if a link is safe? Hover your cursor over it to see if it’s legitimate.

- Delete apps not in use. “You don’t control any of your personal data once you start downloading a few apps,” cautions Harknett. “If that app is sitting on your phone — even if you’re not using it — and it has a vulnerability, it’s an access point to a third party.”

- Beef up your password. Users are often advised to change their passwords frequently, but that might be making us less secure, says Harknett. “People start to use poorer passwords because they have to have so many of them,” he explains. Instead, Harknett recommends making three variations of a really strong password to use across your systems.

- Safeguard sensitive information. “Birthdates, social security, home address — this is stuff that I don’t need to make easier for cybercriminals to find,” says Harknett. “People who use their birthdates as their email are just asking for trouble.”

- Wait to post vacation photos. “If you’re in Hawaii and posting every day and you’ve put pictures on Facebook that has the geolocation setting for your house, I know you’re not at home,” warns Harknett. And as for geolocation settings — embedded code that records the GPS coordinates where a photo was taken — Harknett recommends turning that feature off altogether.

- Create your own security questions. Security questions are often easy to guess. Your favorite vacation spot or the street you grew up on isn’t as top secret as you may think. Harknett recommends you create your own custom security questions or make up answers to pre-selected questions.

- Harness your online network. We snap selfies, check in at happy hours, tweet at our friends and announce major milestones — all private details Harknett warns can be used maliciously by cybercriminals. He recommends setting Facebook accounts to private and limiting your social network. “Be social online, but know with whom you are being social,” says Harknett.

Rachel Richardson

Rachel is a public information officer with the University of Cincinnati and a contributor to UC Magazine. As a former multimedia journalist and two-time alumna of UC's McMicken College of Arts & Sciences, Rachel is thrilled to have the opportunity to share the stories of UC's amazing community of faculty, staff, alumni and students. Rachel.Richardson@uc.edu

FEATURES

UC grad helps fight stigma of mental illness by sharing her own journey from schizophrenia to recovery.

Sisters Lucy and Annette Braun, UC's trailblazing female PhDs, devoted their lives to illuminating nature.

At 150 years, CCM reflects on its humble beginnings and impressive firsts while celebrating successful alumni and campus events.

UC’s All-American thrower became the fifth national champion in Bearcats history.

UC’s Richard Harknett, one of the world’s leading online security experts, reveals the digital threats that keep him up at night.

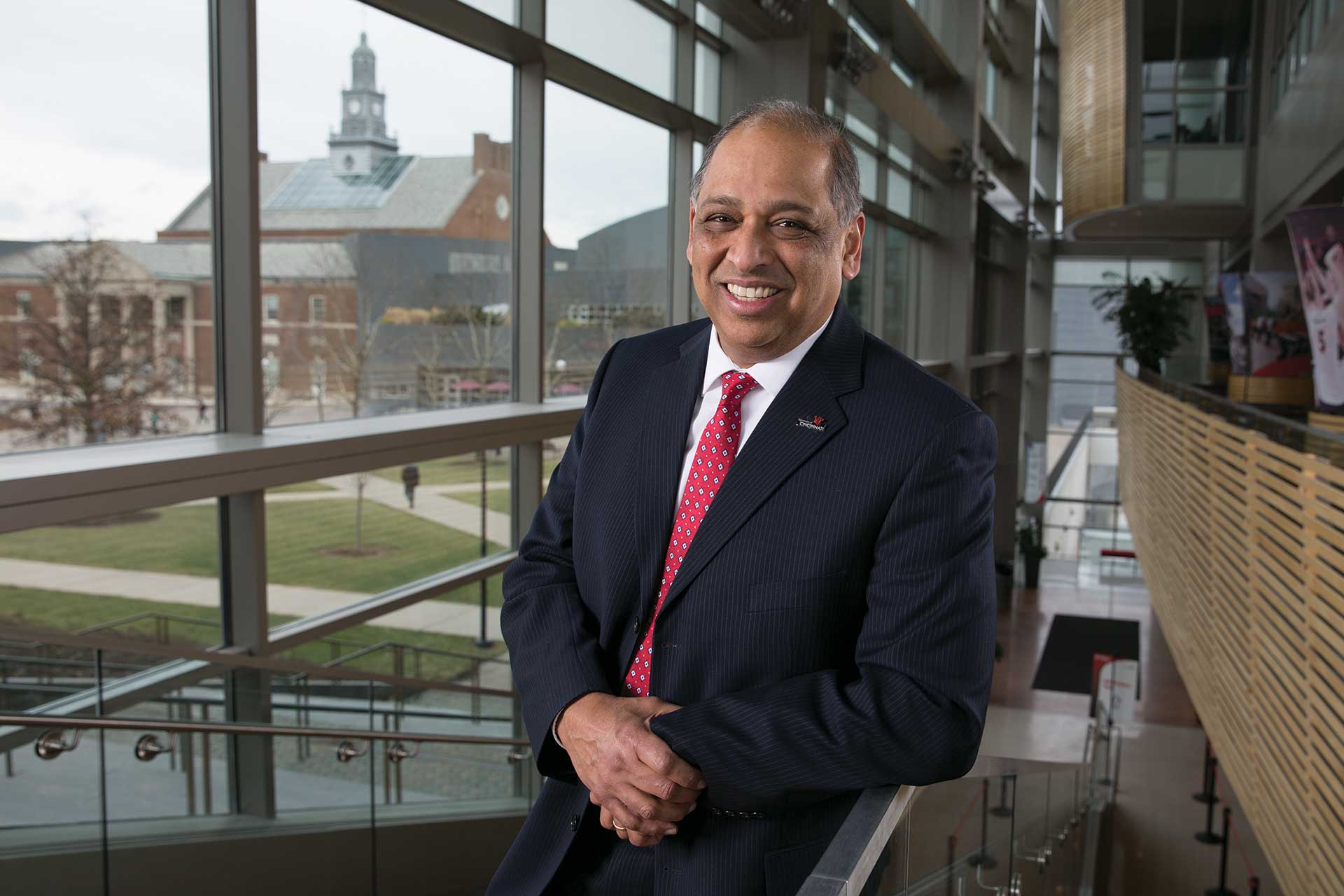

UC President Neville Pinto is back home at the university that launched his career. His mission: to promote the value of higher education.