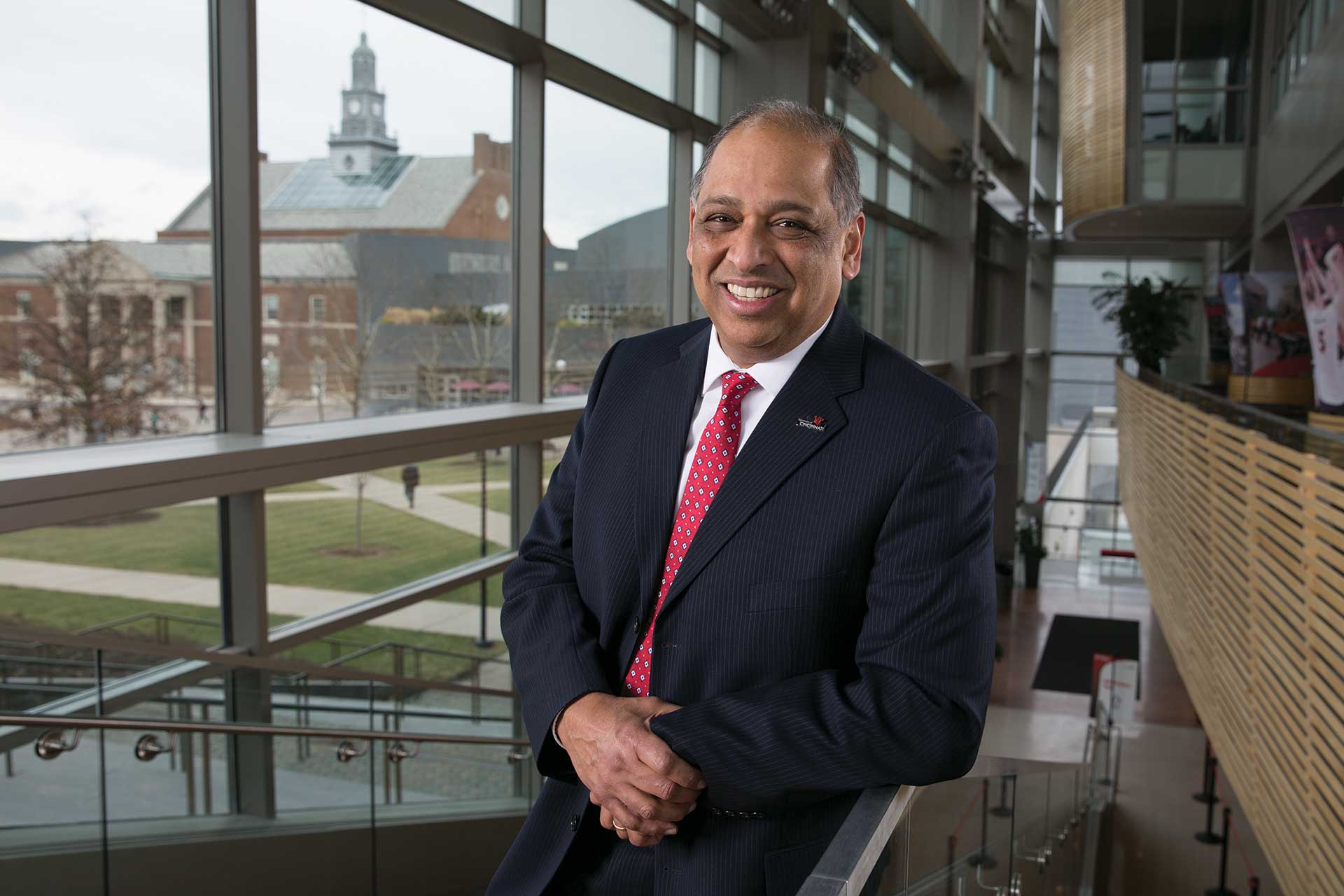

UC President Neville Pinto. photo/Lisa Ventre

UC President Neville Pinto is back home at the university that launched his career. His mission: to promote the value of higher education.

F

orty students smartly dressed sit fidgeting in a circle.

The student orientation leaders prepared for this moment by striking “power poses” like bodybuilders or superheroes, a confidence-building exercise the underlying science of which has been disputed. But on this morning, it works anyway as they introduce themselves in clear voices to their speaker, University of Cincinnati President Neville Pinto.

“What advice do you have for new students?” neurobiology student Catherine Buck asks.

“Create that network of friends,” Pinto says. “They’ll develop relationships that last a lifetime.

“They don’t know it yet, but it’s the best four years of their lives.”

After an eventful six years in Kentucky, Pinto returned in February to the university where he spent 26 years as an esteemed researcher, award-winning faculty member and trusted administrator.

One challenge he faces as UC’s 30th president will be Ohio’s shrinking school-age population. The number of graduating high school seniors is expected to climb for four years before dropping by as much as 20 percent over the subsequent nine years, based on state public school enrollment.

That makes retention especially important, and UC’s retention rate for first-year, full-time baccalaureate students is about 89 percent. Before joining the students in a group photo, Pinto challenges the orientation leaders to help boost retention to 90 percent or better this year.

Pinto, 59, says his goal is not just to brand UC as a premier urban research university but also to promote higher education in general.

“I view the university as the single-most important institution we have. It is about defining our society for the future,” he says.

It starts, he says, by putting the interests of students first. It’s a credo he lives by. His own 26-page resume touts the work of his graduate students before even his own engineering research.

Earlier this year, Pinto hosted an impromptu ice-cream social on the steps of the Tangeman University Center as a morale booster for students during finals week. He posed for selfies and handed out cups of Graeter’s ice cream.

When it comes to students, Pinto says, “I’m certainly there to teach them and help them become consummate professionals that would make me proud as their former teacher. But I also see a role as an adult in their lives not very different from a parent. To me, that’s an important relationship.”

His former engineering students at UC describe him as exacting but patient and helpful.

“He inspired us to do our best and made us feel like our research was important. He taught us to set high standards,” says Blanca Lapizco-Encinas, now an associate professor of biomedical engineering at the Rochester Institute of Technology.

Students pose with President Pinto during an ice cream social. photo/Andrew Higley

Pinto’s intervention at a critical time changed the lives of UC alums Amit Katiyar and Santosh Yadav. The couple met as engineering students in India.

“(Amit) makes me laugh,” Yadav says. “He makes me happy. He makes every stressful situation lighter.”

But Katiyar enrolled in UC’s graduate program in 2002 while Yadav was accepted in Singapore. Pinto found a UC teaching assistantship in mathematics so Yadav could come to Cincinnati. She and Katiyar earned doctoral degrees together in chemical engineering with Pinto as their adviser.

Today, the two UC graduates work for competing Fortune 500 companies in Pennsylvania. They are married with three children.

“If I hadn’t gotten this opportunity, we probably wouldn’t have been together. That’s what brought me here. That’s what helped me have a family,” Yadav says.

Pinto said his own experience makes him sympathetic to the particular stresses faced by UC’s international students.

He grew up in Mumbai, India. He studied chemical engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology before enrolling in graduate school at Penn State University, where his first impression of America was a deserted airstrip outside State College with a note taped to an empty trailer informing arriving passengers to call a taxi.

He didn’t know much about Pennsylvania but applied to Penn State on the advice of a professor. And he got his first job out of college in 1985 by happenstance when he noticed a small blurb in a professional magazine on a new research center at UC.

He would thrive at UC for a quarter century, co-authoring 80 research papers and advising dozens of graduate students as his career propelled him from engineering professor of the year to vice provost and dean of the UC Graduate School.

“I didn’t have a very planned-out life,” Pinto told the student orientation leaders. “If you’re like me, don’t worry, do your best and enjoy what you do. It will all work out.”

The president serves as the public face of the university, and people relate to Pinto when he works a room. But friends and colleagues say that behind the warm smile is a gravitas earned through experience.

“He met important criteria in being a well-published professor with a strong research portfolio,” says Anthony Perzigian, retired provost who led the search that appointed Pinto to his first senior administrative position at UC. “He could serve as an ideal role model for other professors and graduate students. I hit a home run on that one. I can be immodest about that.”

Pinto exhibited his grit soon after leaving UC in 2011 to become dean of engineering at the University of Louisville. He was appointed acting president when Louisville’s president resigned in the wake of multiple scandals.

“He really had a trial by fire there in a chaotic situation. He was the right person to lead the university at a difficult time,” Perzigian adds.

Through it all, his friends and colleagues say, Pinto made time for them.

Despite his lofty academic positions, Pinto has always been approachable, particularly to students, UC engineering professor Richard Miller says.

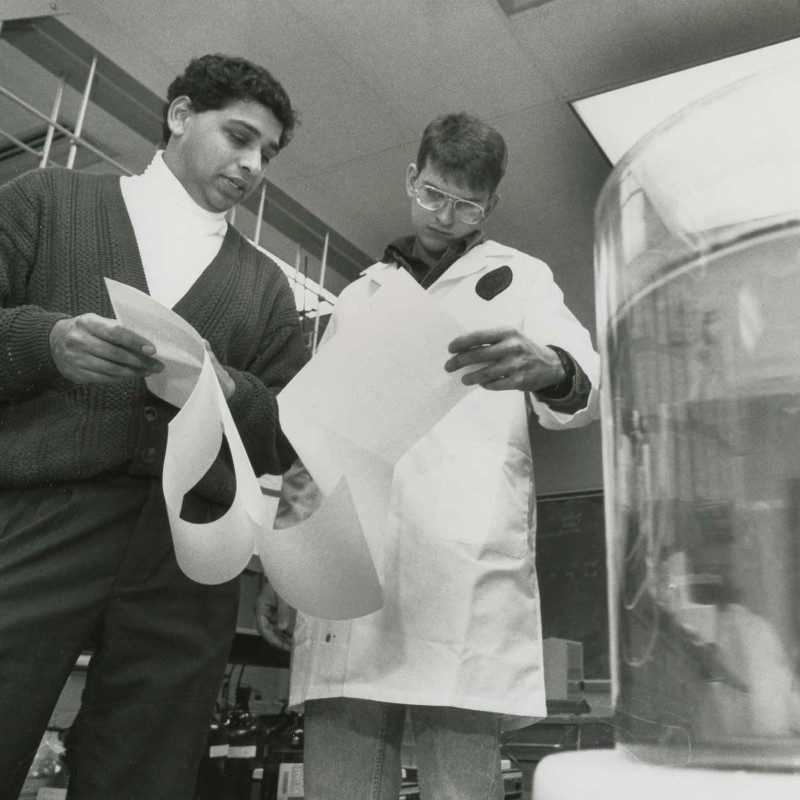

Pinto and Chad Farschman, a UC junior chemical engineering student at the time, discuss the results of a study, in 1993. photo/Lisa Ventre

Neville Pinto with David Jen, his first graduate student.

President Neville Pinto met the media on his first official day as UC's new leader. photo/Lisa Ventre

“He’s a ‘meet him on the back porch for a beer’ kind of guy,” Miller says. “I’m fortunate to count him as a friend.”

When Miller was named interim vice provost under former provost and then interim president Beverly Davenport, he had dinner with Pinto in Louisville to get his advice — wisdom about making hard choices that stuck with him.

Pinto advised him that “two things” can make leadership difficult: You don’t listen to anybody, or you listen to everybody,” Miller says. “Either you don’t think about what people want, or you’re too worried about disappointing people that you don’t do anything.”

Looking to the future, Pinto says he wants UC to play a bigger role in addressing Greater Cincinnati’s and Ohio’s socio-economic challenges. And he wants to make sure UC is recognized for the countless positive influences it exerts every day.

One point of pride is UC’s status as one of just 115 Carnegie Research 1 universities in the United States — a distinction awarded only to universities with extensive research activity.

UC is building on that reputation with the new 1819 Innovation Hub in an old Sears building on Reading Road. At Louisville, Pinto was part of the team that developed a microfactory, called GE FirstBuild, where students collaborated with GE on projects to rapidly bring products to market.

Similarly, the 1819 Innovation Hub will give students a creative space to work with business and industry, he says.

The Bearcat mascot joined in the reception held to welcome back Pinto as UC president along with his family including (from left) daughter, Madeline; son Rui; son, Robbie; and wife, Jennifer. photo/Andrew Higley

“Research institutions would not exist without a supportive and visionary administration,” says John Gant, Louisville’s director of partnerships and alliances. “He saw the potential for what FirstBuild could mean to the university and what a tremendous asset university research brings to the community in terms of economic development.”

Pinto says he is not the type of person to spend sleepless nights worrying — with one exception.

“To me there are huge winds of change in higher education. The cost of education to our students keeps me up at night,” he says.

Pinto says he is looking for innovative solutions such as expanding paid student co-ops, a concept UC pioneered in 1906 that has been replicated at more than 1,000 other colleges around the world.

He believes in the transformative effect of a college education. And before dispatching the student orientation leaders to welcome new Bearcats, he urges them to believe in it, too.

“Don’t forget what you came here for, a degree. But education is more than just good grades,” he says. “Go abroad. Challenge yourself. Be passionate about your studies. But be passionate about the rest of your life.”

Michael Miller

Michael Miller is a public information officer and science writer at the University of Cincinnati and contributes to UC Magazine. mille7m9@ucmail.uc.edu

FEATURES

UC grad helps fight stigma of mental illness by sharing her own journey from schizophrenia to recovery.

Sisters Lucy and Annette Braun, UC's trailblazing female PhDs, devoted their lives to illuminating nature.

At 150 years, CCM reflects on its humble beginnings and impressive firsts while celebrating successful alumni and campus events.

UC’s All-American thrower became the fifth national champion in Bearcats history.

UC’s Richard Harknett, one of the world’s leading online security experts, reveals the digital threats that keep him up at night.

UC President Neville Pinto is back home at the university that launched his career. His mission: to promote the value of higher education.